Early Non-Muslim Sources

The importance of non-Muslim sources, particularly Syriac sources, for understanding the events of the emergence of the new faith of Islam in the Late Antique world was largely neglected by scholars until the beginning of the current millennium. There is still a need for further collaboration between historians, theologians and linguists to promote this endeavour, and to ensure that the nature of Late Antique monotheistic debate and exchange is distributed more widely than has hitherto been the case. This sub-section of the Almuslih Library is an introductory catalogue intended to provide easy access to works, many of which are difficult to find.

Source texts to the year 800 AD

Apocalyptic literature on the conquests

Early apologetics as a historical source

Source texts to the year 800 AD

Later apologetics (post-800 AD)

Jewish and Christian Polemics in Relation to Early Islam

Early non-Muslim sources

Overviews

Bonner, M (ed): Arab-Byzantine Relations in Early Islamic Times, The Formation of the Classical Islamic World, v. 8, Ashgate Variorum 2004.

Borrut, A and Donner, F (edd.) – Christians and Others in the Umayyad State, Late Antique and Medieval Islamic Near East, vol. 1. Chicago 2016.

Brock, S: Syriac historical writing, a survey of the main sources. The Oriental Institute, Oxford.

Brock, S: Syriac Sources for Seventh-Century History, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Vol 2 (1976), 17-36. Blackwell.

Brock, S: Syriac Views of Emergent Islam in Studies on the First Century of Islam, edited by G. H. A. Juynboll, pp.9-21 and 199-203 (Bibliography). Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1982.

Brzozowska, Z, Leszka, M and Wolińska, T: Muhammad and the Origins of Islam in the Byzantine-Slavic Literary Context, A Bibliographical History, Byzantina Lodziensia XLI, Lodz, 2020.

Cameron, A: Patristic studies and the emergence of Islam, in Patristic Studies in the Twenty-first Century: Proceedings of an International Conference to Mark the 50th Anniversary of the International Association of Patristic Studies, 2013 Eds. Brouria Bitton-Askelony, Theodore de Bruyn, Carol Harrison, Oscar Velásquez.

Carrasco, C: La visión inicial del Islam por el Cristianismo oriental. Siglos VII-X in Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Heraicos. Sección Árabe-Islam 61 (2012), pp.61-85.

Cecota, B: Islam, the Arabs and Umayyad Rulers According to Theophanes the Confessor’s Chronography in Studia Ceranea 2, 2012, p. 97–111.

Déroche, V: Polémique Antijudaïque et Émergence de l’Islam, in Dagron, G and Déroche, V, Juifs et Chrétiens en Orient Byzantin, Paris 2010, pp.465-484.

Griffith, S: The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam, Princeton University Press, 2008. Particularly chapter II: Apocalypse and the Arabs: The first Christian Responses to the Challenge of Islam.

Grypeou, E (ed): The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, Leiden / Boston: Brill, 2006.

Howard-Johnston, J: Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Hoyland, R: The Earliest Christian Writings on Muhammad in Motzki, H (ed): The Biography of Muḥammad, The Issue of the Sources, Brill 2000, pp.276-297.

Levy-Rubin, M: Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization, 1, 2011.

Lindstedt, I: Muhammad and his followers in context: The Religious Map of Late Antique Arabia, Brill Leiden and Boston 2023.

Martinez, F: La Literatura Apocalíptica y las Primeras Reacciones Cristianas a la Conquista Islámica en Oriente.Conference paper, Real Academia de la Historia, April 2002.

Maximov, Y (ed): Византийские сочинения об исламе. Том I, (‘Byzantine Writings on Islam’ Vol.1). Texts, translations and commentary. Izdatelʹstvo PSTGU, Moskva, Russia, 2012. Tr. by Y. Maximov and E. Orekhanova.

Mikhail, M: Utilizing Non-Muslim Literary Sources for the Study of Egypt, 500–1000 CE, in Bruning, J and De Jong, J and Sijpesteijn, P (edd.): Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean World From Constantinople to Baghdad, 500-1000 CE,Cambridge University Press 2022, pp.465-492.

Nöldeke, T: Zur Geschichte der Araber im 1. Jahdes. d. H. aus syrischen Quellen, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 29 (1875): 76-98.

Ohlig, K: Die christliche Literatur under arabischer Herrschaft im 7. und 8. Jahrhundert. Inarah.de.

Ohlig, K: Evidence of a New Religion in Christian Literature “Under Islamic Rule”? in Ohlig, K (ed): Early Islam: A Critical Reconstruction Based on Contemporary Sources. Prometheus Books, 2013, pp.176-250.

Palmer, A: The Seventh Century in West-Syrian Chronicles, (with S. Brock and R. Hoyland), Liverpool university Press, 1993.

Penn, M: Envisioning Islam: Syriac Christians and the Early Muslim World. Divinations: Rereading Late Ancient Religion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Penn, M: God’s War and His Warriors: The First Hundred Years of Syriac Accounts of the Islamic Conquests, in Sohail H. Hashemi (ed): Just Wars, Holy Wars, and Jihads: Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Encounters and Exchanges, Oxford University Press, 2012. Part One, Section 3: pp.69-88.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015

Qanawātī, J: المسيحية والحضارة العربية (‘Christianity and Arab Culture’)، Al-Muassasa al- ‘Arabiyya lil-Dirāsa wal-Nashr.

Reinink, G: Early Christian Reactions to the Building of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalemin Христианский ВостокVol. 2, 2001, pp.227-241.

Reinink, G: From Apocalyptics to Apologetics: Early Syriac Reactions to Islam in Brandes, W and Schmieder, S (edd.): Endzeiten – Eschatologie in den monotheistischen Weltreligionen, De Gruyter 2008, pp.75-87.

Reynolds, G.S: نشوء الإسلام – التقاليد الكلاسيكيّة من منظور معاصر (the opening section of The Emergence of Islam, tr. Saʽd Saʽdī and ‘Abbūd Saʽdī), Beirut, Dar al-Machreq, 2017.

Saadi, A-M: Nascent Islam in the Seventh Century Syriac Sources in The Qur’ān in its Historical Context. Edited by Reynolds, Gabriel Said. Routledge Studies in the Qur’ān. London / New York: Routledge, 2007, pp.217-222.

Sahas, D: The Seventh Century in the Byzantine-Muslim Relations: Characteristics and Forcesin Sahas, D: Byzantium and Islam, Collected Studies on Byzantine-Muslim Encounters, Brill, Leiden, pp.256-275.

Sahas, D: Byzantium and Islam, Collected Studies on Byzantine-Muslim Encounters,. Part 1: Mental and Theological Predispositions for a Relationship, or Conflict; Part 2: Historical Preambles under the Sting of the Arab Conquests; Part 3: Damascenica: Part 4: On or Off the Path of the Damascene. Brill, Leiden.

Segal, Judah Benzion, Syriac Chronicles as Source Material for the History of Islamic Peoples, in Historians of the Middle East. Edited by Lewis, Bernard and Holt, Peter Malcolm. London: Oxford University Press, 1962, pp.246-258.

Shahîd, Irfan, Islam and Oriens Christianus: Makka 610-622 AD, in Grypeou, E (ed): The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, Leiden / Boston: Brill, 2006, pp.9-31.

Shoemaker, S: Syriac Apocalypticism and the Rise of Islam

Shoemaker, S: The Apocalypse of Empire: Imperial Eschatology in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Philadelphia PA, University of Pennsylvania Press 2018.

Shoemaker, S: ‘The Reign of God Has Come’: Eschatology and Empire in Late Antiquity and Early Islam, Arabica, Volume 61, Issue 5, 2014, pages 514 – 558.

Suermann, H: Early Islam in the Light of Christian and Jewish Sources, in Angelika Neuwirth, Nicolai Sinai, Michael Marx (edd.), The Qurʾān in Context. Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu, Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān 6, Leiden, Boston 2010, pp.135-148.

Tolan, J: Christian reactions to Muslim conquests (1st-3rd centuries AH; 7th-9th centuries AD) in Volkhard Krech & Marion Stienicke, eds, Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives (Leiden: Brill, 2012, 191-202 [Proceedings of the conference at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum (October 2008)].

Van Breukelen, M: Relations Arabia and Byzantium fifth-ninth century: Muslims, Christians and Jews. Vol.1 History and Historiography, Ridero 2022.

Van Ginkel, J: The Perception and Presentation of the Arab Conquest in Syriac Historiography: How Did the Changing Social Position of the Syrian Orthodox Community Influence the Account of Their Historiographers?,pp.171-184 of Grypeou, E (ed): The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, Leiden / Boston: Brill, 2006.

Wood, P: Christians in the Middle East, 600-1000: Conquest, Competition and Conversion in A. Peacock, B. Da Nicola and S.-N. Yildiz (eds.), The Islamization of Anatolia, c.1100-1500, pp.23-50.

Yadgar, L: Jewish Accounts of Muhammad and His Apostate Informants. Mizan Project.

Collected sourcebooks

Boras, L : “A prophet has appeared coming with the Saracens”: The non-Islamic testimonies on the prophet and the Islamic conquest of Egypt in the 7th-8th centuries. MA Thesis, Radboud University, June 2017.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997.

Hoyland, R: الإسلام كما رآه الآخرون – مسح وتقييم للكتابات المسيحية واليهودية والزردشتية عن الإسلام المبكر (Arabic translation of Seeing Islam as Others Saw It), tr. Hilāl Muḥammad al-Jihād, Maktabat al-‘Awlaqī, Yemen 2024.

Kirby, P: External References to Islam (excerpts from Hoyland: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It).

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015.

Penn, M: حين التقى المسيحيون بالمسلمين أول مرة (Arabic translation of When Christians First Met Muslims, tr. ‘Abd al-Maqṣūd ‘Abd al-Karīm).

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021.

Thomas, D (ed): The Bloomsbury Reader in Christian-Muslim Relations, 600-1500, Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

Source Texts to the year 800 AD

The Teaching of Jacob Διδασκαλία Ίακώβου Νεοβαπτίστου

Fragment on the nomads’ conquests

Stephen of Alexandria Ἀποτελεσματικὴ Πραγματεία πρὸς Τιμόθεον

Chronicle (Thomas the Presbyter) ܡܟܬܒ ܙܒܵܢܐ

Maximus the Confessor Ἐπιστολή Δογματική

St Ephrem’s Homily on the End-Times ܥܠ ܚܪܬܐ ܕܦܣܝܩܬܐ

An Armenian Chronicle Պատմութիւն Սեբէոսի

Coptic Apocalypse of Pseudo-Shenute. نبوة ابينا القديس انبا شنودا

Fredegar Chronicorum Liber Quartus

Letters of Isho’yahb III of Adiabene ܟܬܒܐ ܕܐܓܪܵܬܐ

The Secrets of Rabbi Shim‘ōn ben Yoḥai נסתרות רבי שמעון בן יוחאי

The Chapters of Rabbi Eliezer פִּרְקֵי דְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר

The Panegyric of the Three Holy Children of Babylon Ⲡⲉⲣⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⲛ̄ⲡⲓⲅ̄ ⲛⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲉⲧϧⲉⲛ ⲃⲁⲃⲩⲗⲱⲛ

The Khuzistan Chronicle ܫܪܵܒܐ ܡܕܡ ܡܢ ܬܫܥܝܵܬܐ ܥܕܬܢܝܵܬܐ

The Maronite Chronicle ܡܟܬܒ ܙܒܵܢܐ ܕܣܝܡ ܠܐܢܫ ܕܡܢ ܒܝܬ ܡܪܘܢ

Theophilus of Alexandria’s Homily ميمر قاله انبا تاوفيلس من اجل بطرس وبولس

Anastasius of Sinai Οδηγος – Ερωτησεις και Αποκρισεις

Jacob of Edessa Letters to John the Stylite

The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu

Theophilus of Edessa Chronicle source

John Bar Penkaye ܟܬܒܐ ܕܪܝܫ ܡܠܐ

Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius ܡܐܡܪܐ ܥܠ ܝܘܒܠܐ ܕܡܿܠܟܐ̈ ܘܥܠ ܚܪܬ ܙܒ̈ܢܐ

Edessene fragment of Pseudo-Methodius

Coptic Apocalypse of Pseudo-Athanasius ⲟⲩⲗⲟⲅⲟⲥ ⲉⲁϥⲧⲁⲟⲩⲟϥ ⲡⲉⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲥ

Apocalypse of John the Little ܓܠܝܢܐ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ ܙܥܘܪܐ

Greek Daniel (First Vision) Διήγησις περὶ τῶν ἡμερῶν τοῦ ἀντιχρίστου τὸ πῶς μέλλει γενέσθαι

Ps.-Methodius, Greek addendum Περὶ τοῦ ἀφανισμοῦ τῶν Σαρακηνῶν καὶ τῆς τοῦ κόσμου συντελείας

The Zuqnīn Chronicle ܡܟܬܒܢܘܬܐ ܕܬܫܥܝܬܐ ܕܙܒ̈ܢܐ

Baḫirā (‘Sergius the Monk’) ܬܫܝܬܐ ܕܪܒܢ ܣܪܓܝܣ ܕܡܬܩܪܐ ܒܚܝܪܐ

The Coptic Apocalypse of Daniel ϯⲡⲣⲟⲫⲏⲧⲓⲁ ⲛ̄ⲇⲁⲛⲓⲏⲗ ⲡⲓⲡⲣⲟⲫⲏⲧⲏⲥ

Ghewond’s History Պատմութիւն Ղեւոնդեայ

Later visionary / apocalyptic works

The Apocalypse of Ps. Ezra ܫܐܠܬܐ ܕܫܐܠ ܥܙܪܐ ܥܠ ܥܬܝܵܕܬܐ ܕܒܐܚܪܝܬ ܙܒܢܐ̈

The Apocalypse of Peter كتاب المجال– جليان بطرس

Later non-Muslim historical texts

Theophanes the Confessor Χρονογραφια

Michael the Syrian ܡܟܬܒܢܘܬ ܙܒ̈ܢܐ

< 634

The Teaching of Jacob Διδασκαλία Ίακώβου Νεοβαπτίστου

The Doctrina Jacobi nuper baptizati or Teaching of Jacob newly baptized (dated to July 634 AD) is a series of debates that took place among the Jews of North Africa in response to their forced baptism under Heraclius in 632. One of the discussions mentions in passing a letter that one had recently sent his brother from Palestine, mentioning the recent arrival of the Saracens who had entered the Holy Land under the leadership of a new unnamed prophet who was proclaiming the imminent arrival of the Messiah. Individuals who had met this prophet had said that he was false, ‘for the prophets do not come armed with a sword and a war chariot’ – μὴ γὰρ οἱ προφὴται μετὰ ξίφους καὶ ἂρματος ἔρχονται – and that ‘there was no truth to be found in the so-called prophet, only the shedding of men’s blood. He says also that he has the keys of paradise, which is incredible’. The text implies that the Prophet was still alive and leading his followers as they first entered the Byzantine lands, and that the prophet’s message was eschatological, preaching the end of times when Christ will return. The Greek original of the text has been preserved in a direct but acephalous version and in an abbreviated version, so the main text has to be taken from later Arabic, Ethiopic and Slavic translations. The work remains a subject of controversy, with scholars disagreeing on whether the unnamed prophet, in an age awash of apocalyptic preachers, refers to Muḥammad, or whether it comes from a later date and dependent upon subsequent messianic writings.

Anthony, S: Muhammad, the Keys to Paradise, and the Doctrina Jacobi: A Late Antique Puzzle. Der Islam 2014; 91(2): 243–265.

Dagron, G and Déroche, V: Juifs et Chrétiens dans l’Orient du VIIe Siècle, in Dagron, G and Déroche, V, Juifs et Chrétiens en Orient Byzantin, Paris 2010, pp.47-273. Greek text, French translation and commentary.

Hoyland Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. p.55-61.

Jacobs, A: Teaching of Jacob Newly Baptized. English translation of the text.

Nau, F: La Didascalie de Jacob, Première Assemblée, in Patrologia Orientalis, Vol. VIII, Paris 1912, pp.711-780 (Greek text pp.745-780).

Shaddel, M: Doctrina Iacobi and the Rise of Islam (in Nadine Viermann and Johannes Wienand, Reading the Late Roman Monarchy).

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. pp.37-45.

Van der Horst, P: A Short Note on the Doctrina Jacobi Nuper Baptizati. Brill, Leiden 2009.

Von Sivers, P: Dating the Doctrina Iacobi, an Anti-Jewish Text of Late Antiquity, Inarah Publications, 2022. Dating the “Doctrina Iacobi” and “The Nistarot of Rabbi Simon b. Yohai,” hitherto assumed to have been composed in the 630s, to the end of the seventh century.

John Moschus Λειμών

The Byzantine monk John Moschus (c.550-619) includes among his 300 or so anecdotes on the feats and achievements of holy men in his Pratum Spirituale (Λειμων) some mentions of ‘Saracens’ as predatory creatures whose attacks are foiled by appeals to God or helped by holy men. The accounts give an indication of the worsening conditions that preceded the conquest of Palestine. An appendix to the Georgian version includes a detailed description of the Saracens’ entry into Jerusalem and their immediate construction of a miżgit’a on the Temple Mount.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.61-66.

Sahas, D: Saracens and Arabs in the Leimon of John Moschosin Sahas, D: Byzantium and Islam, Collected Studies on Byzantine-Muslim Encounters, Brill, Leiden, pp.203-217.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. pp.73-80.

Wortley, J: The Spiritual Meadow (Pratum Spirituale), Introduction, Translation and Notes, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1992. The attacks of the ‘Saracens’ are featured in sections 21, 99, 107, 133, 155.

Migne, J: Patrologia Graeca, Pratum Spirituale, Λειμων, Vol. 87, pp.2844-3116. Greek text with Latin translation. Extracted sections 21, 99, 107, 133, 155.

< 637

Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem Epistula Synodica – Εις τα θεια του Σωτηρος Γενεθλια – Εις το Αγιον βαπτισμα

Sophronius was the Patriarch of Jerusalem (d. c.639), who witnessed the first wave of Arab attacks which he recorded in his letters and sermons. He was tasked with collaborating with the invaders and surrendering Jerusalem to ‘Umar. His works significant for early Islam include his Synodical Letter (late 634) in which he refers to the invaders’ ‘wanton acts, full of madness’, who ‘on account of our sins they have now unexpectedly risen up against us and are seizing everything as booty with cruel and savage intent and godless and impious boldness’. In his Homily on the Nativity (25 December 634) he laments the Christians’ inability to travel to Bethlehem due to ‘the sword of the savage and barbaric Saracens which, filled with every diabolical cruelty, striking fear and bringing murder to light, keeps us banished … and threaten slaughter and destruction if we should go forth.’ In his Homily on Epiphany (6 Jan 636 or 637) Sophronius wonders ‘Why is there endless shedding of human blood? Why are the birds of the sky devouring human flesh? Why have the churches been torn down? Why is the cross mocked? Why is Christ, the giver of every good thing and the provider of this our great joy, blasphemed by mouths of heathens?’ They ‘plunder cities, mow down fields, burn villages with fire, set flame to the holy churches, overturn the sacred monasteries … they mock us and increase their blasphemies against Christ and the church and speak iniquitous blasphemies against God. And these adversaries of God boast of conquering the entire world, unrestrainably imitating their general the Devil with great zeal, and emulating his delusion’ – τον στρατηγον αυτων ασχετως Διαβολον μετα πασης σπουδης εκμιμουμενοι. Sophronius ascribes the triumph of these ‘Ishmaelites’ and ‘Hagarenes’ to the sins of Christians, and sees no hope for rescue other than through increased piety.

Allen, P: Sophronius of Jerusalem and Seventh-Century Heresy, The Synodical Letter and other Documents, Oxford Early Christian Texts, 2009, pp.152-155. Parallel Greek text and translation.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.67-73.

Migne, J: Sancti Sophronii Hierosolymitani Epistula Synodica ad Sergium Patriarcham Constantinopolitanum, in Patrologia Graeca, Vol. 87, pp.3147-3200. Greek text and Latin translation of the Synodical Letter, extracted section.

Migne, J: Sancti Sophronii Hierosolymitani Orationes – In Christi Servatoris Natalitia, in Patrologia Graeca, Vol. 87, pp.3201-3212. Latin translation.

Sahas, J: The face to face encounter between Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem and the Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb: Friends or Foes? in Grypeou, E (ed): The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, pp.33-44. Also in Sahas, D: Byzantium and Islam, Collected Studies on Byzantine-Muslim Encounters, Brill, Leiden, pp.141-152.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.45-54.

Usener, H: Weihnachtspredigt des heiligen Sophronius in Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 41 (1886), pp.500-16. Greek text on The Nativity. Mentions of the Saracen threat: pp.506-7, 508, 515.

Papadopoulos-Kerameus, A (ed.): Του εν Αγιοις Πατρος ημων Σωφρονιου Αρχιεπισκοπου Λογος εις το Αγιονβαπτισμα, in Αναλεκτα Ιεροσολομιτικης Σταχυολογιας Vol. 5, St Petersburg 1898, pp.151-168. Greek text on The Epiphany / Holy Baptism. The passage on the Saracens begins at Section 10 (p.166).

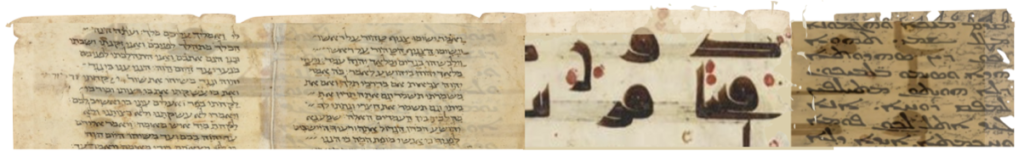

Fragment on the nomads’ conquests

Some notes were written around the year 637 AD on the front blank pages of a sixth-century Syriac manuscript of the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. These notes referenced the attacks by the ‘nomads’ (ṭayyāyē) and gave the first explicit reference to Muḥammad (ܡܘܚܡܕ mūḫmd) by name in history. They mention how ‘many towns were destroyed in the slaughter by [the nomads of] Mūḫmd and many people were slain and taken prisoner … about fifty thousand’ and also intriguingly suggest that Muḥammad was still alive in 636 at the battle of Yarmouk (‘Gabitha’ in the text), contradicting the traditional Muslim accounts of the date of his death.

Brooks, E: Chronica Minora II, p.75 (Syriac text).

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.116-117.

Nöldeke, T: Zur Geschichte der Araber im 1. Jahrh. d. H. aus syrischen Quellen, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 29 (1875): pp.77-82 (Syriac text and translation).

Palmer, A: The Seventh Century in West-Syrian Chronicles, (with S. Brock and R. Hoyland), Liverpool university Press, 1993, pp.2-4.

Palmer, A : Une chronique syriaque contemporaine de la conquête arabe: essai d’interprétation théologique et politique,in La Syrie de Byzance a l’Islam, VIIe–VIIIe siècles. Actes du Colloque international, Lyon–Maison de l’Orient Méditerranéen, Paris – Institut du Monde Arabe, 11–15 Septembre 1990. Edited by Canivet, Pierre and Rey-Coquais, Jean-Paul. Publications de l’Institut français de Damas 137. Damascus: Institut Français de Damas, 1992, pp.31-46.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.21-24.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.55-56.

Stephen of Alexandria Ἀποτελεσματικὴ Πραγματεία πρὸς Τιμόθεον

Stephanos Alexandreus (c.580 – c.640) was a Byzantine Greek philosopher who also wrote works on alchemy and astrology. In his Definitive Treatise addressed to his disciple Timotheos he mentions the emergence of a ‘new and godless lawgiving of Muḥammad’ (νεοφανῆ καὶ ἄθεον νομοθεσίαν τοῦ Μωάμεδ) and relates an intriguing anecdote told by a guest, an Arab merchant who had called in on him on the 3rd day of the month Thoth. This visitor mentioned how ‘In the desert of Ethrib there had appeared a certain man from the so-called tribe of Quraysh (Κορασιανων),of the genealogy of Ishmael, whose name was Muḥammad and who said he was a prophet … He has brought a new expression and a strange teaching (καινοφωνιας και διδαχην εξηλλαγμενην), promising to those who accept him victories in wars, domination over enemies and delights in paradise.’ At the request of the merchant, Stephen then casts a horoscope concerning this self-proclaimed prophet and his followers, and divines the length of future Arab domination to be ‘12 revolutions of Saturn’. The horoscope gives astrological details of the character of 21 Arab sovereigns and the events of their reigns, ending with Al-Mahdī (r.775-785), indicating that if the anecdote of the Arab merchant dates from the lifetime of Stephen, the text of the astrological prediction is a later interpolation. The horoscope concludes with a warning to ‘keep it to yourself, due to the changeability of the times and the cruelty of those in power’.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.302-305.

Papathanassiou, M: Stephanos of Alexandria: A Famous Byzantine Scholar, Alchemist and Astrologer, 2016.

Papathanassiou, M: Stephanos Von Alexandreia und Sein Alchemistisches Werk, Critical Edition, Athens, 2017.

Usener, H: De Stephano Alexandrino, 17-31 repr. in Usener, H: Kleine Schriften, III, Berlin 1914, pp.266-87. Greek text (the account of the Arab merchant appears on p.272 and the horoscope of the Arab kings: pp.279-286).

< 640

Chronicle (Thomas the Presbyter) ܡܟܬܒ ܙܒ̈ܢܐ

Part of a collection of historical texts compiled by an anti-Chalcedonian priest named Thomas, soon after Muḥammad’s followers invaded Mesopotamia in 639-640. One of the entries also gives one of the first explicit mentions of the name Muḥammad (ܡܿܚܡܛ maḫmṭ) when it states that ‘there was a battle between the Romans and the nomads of Muhammad in Palestine near Gaza …. Four thousand poor peasants of Palestine were killed .. and the nomads devastated the entire region’ and the work appears to reference the same incursions mentioned in the Doctrina Jacobi.

Brooks, E: Chronica Minora II, pp.147-8 (Syriac text).

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, p.119.

Palmer, A: The Seventh Century in West-Syrian Chronicles, (with S. Brock and R. Hoyland), Liverpool university Press, 1993, pp.5-12.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.25-28.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.60-61.

Maximus the Confessor Ἐπιστολή Δογματική

In a letter dated between 634 and 640 Peter the governor of Numidia, the theologian Maximus indicates the importance of prayer (writing between 634 and 640), and in passing refers to grave unfolding events, as people are seeing ‘this barbarous people from the desert overrunning another’s lands as if they were their own’ as civilisation is being ‘ravaged by wild and untamed beasts whose form alone is human’. The Arab incursions are seen as part of the eschatological drama in which the Jews are accused as occupying the leading role.

Benevich, G: Christological Polemics of Maximus the Confessor and the Emergence of Islam onto the World Stage in Theological Studies, 2011.

Brock, S: An Early Syriac Life of Maximus the Confessor, in Analecta Bollandiana, Revue critique d’hagiographie, Vol. 1, Bruxelles, 1973, pp.299-346. Syriac text and English translation.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, p.76.

Maximus, Epistula 14, Πρός Πέτρον ἰλλούστριον ἐπιστολή δογματική in Migne Patrologia Graeca 91, 537-540. Extract from the Greek text.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.62-68.

Sahas, D: The Demonizing Force of the Arab Conquests: The Case of Maximus (ca. 580–662) as a Political “Confessor” in Sahas, D: Byzantium and Islam, Collected Studies on Byzantine-Muslim Encounters, Brill, Leiden, pp.236-255. (Ἐπιστολή Δογματική pp.241-243).

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.57-59.

< 650

St Ephrem’s Homily on the End-Times ܥܠ ܚܪܬܐ ܕܦܣܝܩܬܐ

This memrã or verse homily, falsely attributed to St Ephrem (306-373), dates from the mid-640s, and the last historical events to which the apocalypse refers are the Near Eastern invasions by Muhammad’s followers in which ‘a people will emerge from the wilderness, the progeny of Hagar, the handmaid of Sara’. It is one of the first examples of an apocalyptic interpretation of the events of this period, by which Jerusalem features as the pivotal point of a divinely chosen, imminent eschatological empire that would subdue the world and hand over authority to God. Borrowing the imperial eschatology themes of the triumph of Christianity over Rome in the 4th century, the vision depicts the defeat of Persia by the Romans, to be followed by the victory of the descendants of Hagar (the Ishmaelites) who will drive the Romans from the Holy Land – a theme to be incorporated later in the Qur’ān (sūra XXX – ‘al-Rūm’ – verses 2-4).

Alexander, P and Abrahamse, D (edd): The Byzantine apocalyptic tradition, University of California Press1985, pp.136-147.

Beck, E (ed.): Des heiligen Ephraem des Syrers Sermones III (CSCO 320; Louvain: Secrétariat du Corpus SCO, 1972), 60-71. English translation: Ephrem: A Discourse (memra).

Lamy, T ed.,: Sermo II – Mar Ephraemi de fine extremo in Sancti Ephraem Syri Hymni et Sermones, Mechliniae: H. Dessain, 1882-1902, Vol. 3: pp.187-212. Syriac text and Latin translation.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.37-47.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.80-93.

An Armenian Chronicle Պատմութիւն Սեբէոսի

An anonymous chronicle, traditionally attributed to a Bishop Sebeos and which relates events in the mid-650s, concluding with al-Mu‘āwiya’s victory in the First Civil War. The chronicle gives valuable information on the rise of the new believers, most probably relying on an earlier source dating from the 640s. It speaks of the rise of a preacher from the sons of Ishmael, and couches the narrative in Biblical references. It narrates how the preacher called for ‘fulfilling the promise to Abraham’, legislated laws (but without any mention of a ‘scripture’) and how ‘all the remnants of the people of the children of Israel assembled, they joined together, and they became a large army’ – indicating what appears to be an interconfessional community of the Believers. But it also speaks subsequently of ‘the plots of the seditious Jews, who when they secured an alliance with the Hagarenes for a little while, devised a plan to rebuild the Temple of Solomon … and when the Ishmaelites became envious of them, they drove them out from that place and called the same house of prayer their own.’

Abgaryan, G: Պատմութիւն Սեբէոսի, Erevan 1979. The critical Armenian edition.

Howard-Johnston, J: The History of Khosrov in Howard-Johnston, J: Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp.70-102 (‘History of Khosrov’).

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.124-131.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.62-72.

Thomson, R and Howard-Johnston, J: The Armenian History Attributed to Sebeos, Liverpool, 1999.

Thomson, R: Muhammad and the Origin of Islam in Armenian Literary Tradition, in Armenian Studies in Memoriam Haig Berberian, Dickran Kouymjian, (ed) Lisbon 1986, pp.829-858.

Coptic Apocalypse of Pseudo-Shenute. نبوة ابينا القديس انبا شنودا

A short historical apocalypse, most likely composed about the year 644 by a Coptic miaphysite author in Shenute’s ‘White Monastery’ in Middle Egypt, and preserved as part of an Arabic and an Ethiopic version of the Life of Shenute. It consists of a prophecy of Christ to the Coptic saint Shenute (d. 464) about the end of time. The prophecy includes references to the Sasanian occupation of Egypt (619-29), the rule of Cyrus al-Muqawqis (631-42), and the Arab conquests. In addition, an historical passage gives a brief account of Muslim rule, mentioning harassment of the population, the wrongful gathering of possessions, and people abandoning Christ’s church owing to oppression. The text gives the impression of having been written to counter the threat of conversion to Islam, implicitly comparing the Muslim rulers with the Antichrist. The text states that after the trials of the Persian occupation (619-628) ‘the sons of Ishmael and the sons of Esau will arise, and they will pursue the Christians. And the rest of them will want to rule over the entire world and dominate it, and they will build the Temple in Jerusalem. When that happens, know that the end of time approaches and has drawn near. And the Jews will expect the Antichrist and will be ahead of the peoples at his arrival’ after which they will see ‘the [abomination of] desolation of which the prophet Daniel spoke standing in the holy place, [know that] they are those who deny the pains which I received upon the cross and who move freely about my church, fearing nothing at all’. The construction of a sanctuary on the Temple Mount, with the Jews taking the lead, and its interpretation as the fulfilment of the Gospel prophecy on the ‘Abomination of Desolation’ (Matthew 24:15-16), something ’set up’ on the Temple Mount, is a common topos in Apocalyptic literature but is here linked with the new construction by the new Believers taking place on the Temple Mount. The ‘Sons of Esau’ here in alliance with the sones of Ishmael reflects early accounts of there being among the Arab invaders some Christian contingents (here understood as ‘heretical Byzantine Diophysites’ persecuting the ‘true Miaphysite Christians’ of Egypt), supporting the hypothesis that the Arab invaders’ community of the Believers predated the formation of a new distinct ‘religion’.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.279-281.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.171-184.

Van Lent, J: The Apocalypse of Shenute, in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History 1, 600-900, ed. D. Thomas and B. Roggema, (History of Christian Muslim Relations 11), Leiden and Boston 2009, pp.182-185.

Van Lent, J: The Prophecies and Exhortations of Pseudo-Shenute in Thomas, D and Mallett, A: Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History 5, 1350-1500, Brill 2013, pp.278-286.

Fredegar Chronicorum Liber Quartus

An anonymous Frankish chronicle latterly attributed to one Fredegar, begins with the creation of the world and ends in AD 642. It reproduces the echoes of the cataclysmic defeat of the Byzantines, most probably the Battle of Yarmuk in 636, at the hands of the Saracens – ‘a race that had grown so numerous that at last they took up arms and threw themselves upon the provinces of the Emperor Heraclius’. Following the Byzantines’ defeat as a result of being ‘smitten by the sword of God’, it tells of how the Saracens ‘proceeded – as was their habit – to lay waste the provinces of the empire that had fallen to them. Heraclius felt himself impotent to resist their assault and in his desolation was a prey to inconsolable grief.’

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.217-219.

Wallace-Hadrill, J: Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its continuations. Latin text and English translation. See pp.54-55.

< 660

Letters of Isho’yahb III of Adiabene ܟܬܒܐ ܕܐܓܪ̈ܬܐ

Patriarch Ishoʻyahb III (d. 659) was a high-ranking cleric in Mesopotamia. Of his 106 letters three in particular are important for references to the new believers, even though in these his primary interest was the doctrinal probity of his bishops and flock. Letter 48b includes the first mention of the term Hagarenes ( ܡܗܓܪܝܐ mhaggrãyē) indicating a specific group of Arabs, most probably the community of muhājirūn, ‘emigrants’ that had undertaken a hijra to the Roman and Persian lands, with the term only later coming to refer to Muḥammad’s hijra from Makka to Madina.. Letter 14c speaks of ‘Arabs to whom at this time God has given control over the world’, and laments the shortcomings of Christians whom ‘the Sheol of apostasy has suddenly swallowed’ particularly since the Arabs are ‘not only no enemy to Christianity, but they are even praisers of our faith, honourers of our Lord’s priests and holy ones, and supporters of churches and monasteries.’ Ishoʻyahb notes that the inducement to apostasy was to avoid the Arabs’ demands on their possessions and the imposition of a poll tax.

Bcheiry, I: An Early Christian Reaction to Islam: Išū‘yahb III and the Muslim Arabs, Gorgias Press, 2019. Excerpts in Syriac and English.

Duval, R: Išō‘yahb Patriarchae III Liber Epistularum, in Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, Scriptores Syri, Series Secunda, Tomus LXIV, Textus Leipzig: Otto Harrassowitz, 1904. The Syriac texts.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.174-182.

Ioan, O – Muslime und Araber bei Īšōʻjahb III (649-659), Harrassowitz, Göttinger Orientforschungen, Reihe 1, Syriaca, Vol.37, 2009.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.29-36.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.93-100.

The Secrets of Rabbi Shim‘ōn ben Yoḥai נסתרות רבי שמעון בן יוחאי

A Judaic messianic interpretation ascribed to the 2nd century Rabbi, but composed in the mid-seventh century, intimating that Muḥammad is a messianic deliverer divinely chosen to liberate the Jews and their Promised Land from Rome’s oppressive yoke. The ‘Kenite’ of Numbers 24.21 is revealed to him as a prophecy about the Ishmaelites and their coming dominion over the land of Israel. The angel Metatron appears to him and reassures him that God will use the Ishmaelites to free the Jews from Byzantine oppression as the fulfilment of the messianic deliverance foretold in Isaiah’s vision of the two riders (Isaiah 21.6–7) and also in Zechariah 9.9. Muhammad’s successor (i.e. ʿUmar) will restore worship to the Temple Mount. The apocalypse then forecasts the Abbasid revolution, which augurs the beginnings of a final eschatological conflict between Israel and Rome to usher in a two-thousand-year messianic reign, followed by the final judgment. Muhammad’s early followers took a keen interest in restoring worship to the Temple Mount, indicating a close affiliation with Judaism that was severed only in the mid-eighth century by which time Islam had developed into a new, distinctive religious confession that drew a sharp boundary between itself and other faiths.

Crestani, S: The Prayer of R. Šim’on b. Yoh’ai between Text, Revelations and Prophecies ex eventu in Materia Giudaica2022.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.308-311.

Reeves, J: Tefillat Rabbi Shim’on b. Yohai in Reeves, J: Trajectories in Near Eastern Apocalyptic: A Postrabbinic Jewish Apocalypse Reader, 2005. (An expansion of the text of The Secrets).

Reeves, J: The Secrets of R. Šim‘ōn ben Yoḥai in Trajectories in Near Eastern Apocalyptic: A Postrabbinic Jewish Apocalypse Reader, 2005, pp.76-89.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.139-143. Translation of the first part of the text.

Spurling, H and Grypeou, E: Pirke de-Rabbi Eliezer and Eastern Christian Exegesis in Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 4 (2007), pp.217-243.

The Chapters of Rabbi Eliezer פִּרְקֵי דְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר

Falsely attributed to Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (1st – 2nd c. AD), the text, which appears to have been compiled in the early Islamic period in Palestine but includes earlier materials, predicts the role of Ishmael’s descendants in the events of the eschaton and contains details that lead to its being dated to around 660 AD. It notes how the Ishmaelites ‘will build a building on the Temple’ indicating the Jewish belief that the arrival of the sons of Ishmael and their rule are signs that the Messiah and the End of Days would soon arrive. The text anticipates a future moment when both the Christian and Muslim empires will be annihilated by the power of God when ‘the Holy One, blessed be He, is going to destroy the descendants of Esau, for they are the adversaries of the children of Israel, and likewise (He will destroy) the Ishmaelites, for they are enemies.’ להשמיד לבני עשו שהם צריו לבני ישראל וכן לבני ישמעאל שהן אויבין . It also mentions that ‘two brothers will rise as rulers over them, whom scholars have identified with ʿAbd al-Malik and his brother ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, or alternatively Mu‘āwia and Ziyād ibn Abī Sufyān.

Adelman, R: The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha, in Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 140, Brill 2009.

Fernández, M: Los Capítulos de Rabbí Eliezer, Valencia 1984. Spanish translation.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.313-316.

Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer: Sefaria.org (Online Hebrew text and English translation).

Reeves, J: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer 30 in Trajectories in Near Eastern Apocalyptic: A Postrabbinic Jewish Apocalypse Reader, 2005.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.144-149.

The Panegyric of the Three Holy Children of Babylon Ⲡⲉⲣⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⲛ̄ⲡⲓⲅ̄ ⲛⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲉⲧϧⲉⲛ ⲃⲁⲃⲩⲗⲱⲛ

An anonymous source, preserved in a 12th century manuscript, that was probably written shortly after the Arab invasions (circa 650s). The text discusses the exodus from paradise, Christ and the story of Daniel, but contains an early reference to the ‘Saracens’, stating ‘let us not fast like the deicidal Jews; neither let us fast like the Saracens, oppressors who follow after prostitution and massacre, and who lead the sons of men into captivity, saying ⲧⲉⲛⲉⲣⲛⲏⲥⲧⲉⲩⲓⲛ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲧⲉⲛϣⲗⲏⲗ ⲉⲩⲥⲟⲡ “We fast and pray at the same time”’. it thus gives an early record of the Coptic sentiment that the Muslims were not liberators but oppressors.

De Vis, H: Homélies coptes de la Vaticane, in II Cahiers de la Bibliothèque Copte, 6, Kopenhagen, 1929, pp.64-120. Coptic text and French translation.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, p.120.

Suermann, H: Copts and the Islam of the Seventh Century in Grypeou, E (ed): The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam, pp.107-109.

< 670

The Khuzistan Chronicle ܫܪ̈ܒܐ ܡܕܡ ܡܢ ܬܫܥܝܵܬܐ ܥܕܬܢܝܵܬܐ

Dated to around 660 the anonymous Chronicle (also known as the Anonymous Guidi) includes an account of the appearance of Muḥammad’s followers the ‘sons of Ishmael’, including the earliest attacks on Syro-Palestine but focussing on Khuzistan in particular, listing the progress of the conquests in sequence. It assumes Muḥammad as still alive leading the invasions against the Sasanians. The Nestorian author of the Chronicle also reports on the ‘tent of Abraham’ located in a remote part of the desert as an important cultic site for the Believers, and gives the first non-Qur’ānic reference to Madina/Yathrib. By referring to a King Mundhir as ‘the sixth in the line of the Ishmaelite kings’ the chronicler took the present invaders to be a continuation of the Lakhmid line, rather than as a new power. The invaders are portrayed as violent, including towards Christians, but also concerned to appropriate the relics of the Prophet Daniel, as an indication of their pre-occupation with Biblical authentication.

Guidi, I (ed): Chronica Minora, in Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, Series Tertia – Tomus IV of Scriptores Syri, Paris 1903, pp.15-39. Syriac text.

Howard-Johnston, J: The Khuzistan Chronicle in Howard-Johnston, J: Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp.128-135.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.182-188.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.47-53.

Robinson, C: The conquest of Khuzistan: a historiographical reassessment, Bulletin of SOAS, 67, 1 (2004), pp.14-19.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.128-137.

The Maronite Chronicle ܡܟܬܒ ܙܒ̈ܢܐ ܕܣܝܡ ܠܐܢܫ ܕܡܢ ܒܝܬ ܡܪܘܢ

An untitled, and highly debated, account that includes episodes from the caliphate of Mu‘āwiya, including his adjudicating debates between Jacobites and Maronites, and his visiting of places associated with the life of Christ: Golgotha, Gethsemane and the tomb of Mary, at all of which he prayed ( ܘܨܿܠܝ ܒܗ ) . There is also a mention of the formula ‘God is great’ ( ܐܠܗܐ ܪܒ ܗܘ Alāhā rabb hū ). The text takes the Arab raids up to Pergamum and Smyrna in the year 663/4.

Breydy, M: Geschichte der syro-arabischen Literatur der Maroniten vom VII. bis XVI. Jahrhundert (Opladen: Westdeutscher, 1985).

Brooks, E (ed): Chronica Minora, in Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, Series Tertia – Tomus IV of Scriptores Syri, Paris 1904, pp.43-74. Syriac text.

Howard-Johnston, J: The Maronite Chronicle in Howard-Johnston, J: Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp.175-178.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.135-139.

Palmer, A: The Seventh Century in West-Syrian Chronicles, (with S. Brock and R. Hoyland), Liverpool university Press, 1993, pp.29-35.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.54-61.

Theophilus of Alexandria’s Homily ميمر قاله انبا تاوفيلس من اجل بطرس وبولس

Preserved in Arabic, possibly as a translation from Coptic or perhaps Greek, the ‘Homily in honour of Peter and Paul’, is claimed to have been given by Theophilus, patriarch of Alexandria (385-412), but contains one of the earliest Coptic references to Islamic rule. The text, which is held to date from the 7th century, retains a tone of antipathy to Byzantium and appreciation of Arab domination. It begins with a short vaticinium ex eventu in which St Peter relates how Athanasius’ see will be the only one to remain firm in the true faith, and how God will then remove the Byzantines from the land of Egypt and establish ‘a strong nation that will have care for the churches of Christ and will not sin against the faith in any way’ ويقيم امة قوية تشفق على بيع المسيح ولا يخطوا الى الامانة بشيء من الانواع but nevertheless God will ‘punish through these people the people of Egypt due to their sins’ ۄﯾﺆدب الله اهل ديار مصر من تلك الامة من اجل خطاياهم . The text thus stands at the point where, after half a century of peace and relief from Byzantine oppression the country is witessing the first effects of a changing attitude of Muslim rulers towards their Christian subjects, in the form of swingeing tax measures and intensified religious assertiveness.

Fleisch, H – Une homélie de Théophile d’Alexandrie en l’honneur de St Pierre et de St Paul in Revue de l’Orient Chrétien 30 Tome X (1935- 36) 371-419. Arabic text and French translation.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, p.172.

Van Lent, J: The Arabic Homily of Pseudo-Theophilus of Alexandria in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History 1, 600-900, ed. D. Thomas and B. Roggema, (History of Christian Muslim Relations 11), Leiden and Boston, 2009, pp. 256-260.

< 690

Anastasius of Sinai Οδηγος – Ερωτησεις και Αποκρισεις

Born in Cyprus, Anastasius travelled widely in the Holy land before settling, in 680 at the monastery of the Theotokos at Mount Sinai (today the monastery of St. Catherine). Of hiσ many works the most relevant for early Islam are his Hodegos(‘Guide’) in which he notes how the ‘Arabs’ regularly misinterpret Christian doctrine as maintaining ‘two Gods’ and blasphemously assume the ‘birth of God’ as involving ‘marriage and insemination and carnal union’ – an indication of growing theological faultlines. His Questions and Answers highlight scriptural and doctrinal issues , the problems of living under the domination of non-Christians (‘if our rulers are Jews or infidels, or heretics, surely we should not have prayers for them in church?’ and occasionally refer to the erroneous beliefs of the Arabs. His Narrations, a collection of edifying tales, and dating possibly to between 640 and 660, provide insights to aspects of day-to-day Christian-Muslim relations in this period, one in which the followers of Muḥammad are represented as wicked and blasphemous oppressors of the Christians, ‘the demons name the Saracens as their companions. And it is with reason. The latter are perhaps even worse than the demons … these demons of flesh trample all that is under their feet, mock it, set fire to it, destroy it’. His accounts are often pious tales of Christian perseverance in their faith, and in one case the first recorded act of martyrdom at the hands of these Believers, including an execution for apostasy. The narrations also include contemporary events, such as news of building works upon the Temple Mount – a reference to the Dome of the Rock, and thus predating the Islamic traditional date of its founding. A particularly interesting reference is made to some Christians’ observations on a place ‘where those who hold us in slavery have the stone and the object of their worship’, and where innumerable sacrifices of sheep and camels are made. The puzzle is whether to consider this a reference to Makka, or some other location that predates the Hijazi shrine.

Griffith, S: Anastasios of Sinai, the Hodegos, and the Muslims in The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 32 (1987), pp.341–58.

Haldon, J: The works of Anastasius of Sinai: A key source for the History of Seventh-Century East Mediterranean Society and Belief in Cameron A and Conrad L: The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East, Princeton 1992.

Hansen, B: Making Christians in the Umayyad Levant: Anastasius of Sinai and Christian Rites of Maintenance, in Studies in Church History 59 (2023), pp.98–118.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.92-102.

Nau, F: Le Texte grec des récits utiles à l’âme d’Anastase le Sinaïte, Gorgias Press, 2009.

Richard, R and Munitiz, J (edd): Anastasii Sinaïtae: Quaestiones et responsiones. CCSG 59. Turnhout, 2006.

Sahas, D: Anastasius of Sinai (c. 640–c. 700) and “Anastasii Sinaitae” on Islamin Sahas, D: Byzantium and Islam, Collected Studies on Byzantine-Muslim Encounters, Brill, Leiden, pp.174-181.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.101-127.

Uthemann, K: Anastasios Sinaites: Byzantinisches Christentum in den ersten Jahrzehnten unter arabischer Herrschaft,Teilband I, De Gruyter, 2015.

Adomnán De Locis Sanctis

Adomnán of Iona (ca. 628–704) was the Irish abbot of Iona Abbey (western Scotland). His work On the Holy Placespresented to King Aldfrith of Northumbria before 688 is the first description of the holy sites of Jerusalem and Palestine following the Arab conquest. In amongst the details of holy places visited by pilgrims Adomnan provides interesting details of life under the new Arab masters. He quotes an account given him by a Frankish bishop from Gaul, Arculf, that ‘where once the Temple had been magnificently constructed, located near the wall on the east, now the Saracens have built a quadrangular house of prayer, which they constructed poorly by standing boards and great beams over some of the remains of its ruins.’ This gives another indication of the early cultic pre-occupation of the Arabs with the Temple Mount, and their building of what may have been a precursor to the Dome of the Rock or of the Al-Aqsa Mosque or the Stables of Solomon.

Geyer, P: Itinera hierosolymitana saecvli IIII–VIII in Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 39. Vienna 1898, pp.219-297.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.219-221.

Meehan, D. (ed.): Adomnan’s ‘De Locis Sanctis’ in Scriptores Latini Hiberniae 3. Dublin, 1958. 1–34. Latin text and English translation.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.164-170.

Wilkinson, J: Jerusalem pilgrims before the Crusades, Warminster 1977, pp.93-111. English translation.

Jacob of Edessa: Letters to John the Stylite

In a series of letters Jacob of Edessa (d. 708, and bishop from 684-688) deals with matters such as whether to make altar coverings with materials on which the profession of faith of the ‘Hagarenes’ ( ܬܘܕܝܬܐ ܗܓܪܝܬܐ tawdītha hāgāraythā) is embroidered, or whether one-time Christian converts to the Hagarenes, on returning to Christianity, should be granted baptism or not. Another indication of the atmosphere of the times is his second letter to John in which he argues that it is best that the doors of a church be closed when the Eucharist is offered ‘especially because of the Hagarenes, so that they might not enter, mingle with believers, disturb them and ridicule the holy mysteries’. He notes how the Hagarenes acknowledge that Christ ‘is the true messiah who was to come and who was foretold by the prophets … and they call him the Word of God’ although denying that he is the Son of God. And in one particularly interesting communication, the Fourth Letter to John the Stylite, Jacob writes of how the Hagarenes ( ܡܗܓܪܝܐ mhaggrãyē), even those resident in Egypt, do not face south while worshipping but ‘worship toward the east, toward the Kaʻba’, that the Hagarenes in Ḥira (Kufa) and Basra ‘pray to the west toward the Kaʿba’. The implication is that the Kaʿba of the Hagarenes does not appear to be located in Makka, for which the Hagarenes in Egypt would have to pray directly southwards, but somewhere in Palestine, that is, eastof Egypt and west of Mesopotamia. It appears then that this Kaʿba would have to be sited at Jerusalem or not too far from Jerusalem.

Hoyland, R: Jacob of Edessa on Islam in After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J.W. Drijvers. Edited by Reinink, Gerrit J. and Klugkist, Alex C.. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 89. Louvain: Peeters, 1999, pp.149-160.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.160-167. See also pp.565-6 in Chapter 13: ‘Sacred direction in Islam’.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.160-174.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.202-208.

Ter Haar Romney, R: Jacob of Edessa and the Syriac Culture of His Day, in Peshitta Institute Leiden, 2009.

Van Ginkel, J: Greetings to a Virtuous Man: The Correspondence of Jacob of Edessa in Ter Haar Romney, R – Jacob of Edessa and the Syriac Culture of His Day, in Peshitta Institute Leiden, 2009, pp.67-82.

The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu

An Egyptian Coptic bishop Nikiu in the Nile Delta and general administrator of the monasteries of Upper Egypt in 696. Although the part of the Chronicle concerning Egypt was written in Coptic it is extant only in an Ethiopic translation. The most important section of John’s Chronicle is that which deals with the invasion and conquest of Egypt by the Muslim armies of ‘Amr ibn al-‘Āṣ, for which the Chronicle provides the sole near-contemporary account, detailing how the Byzantine troops were weakened in their morale by the hostility of the native inhabitants ‘towards the Emperor Heraclius because of the persecution he launched over all Egypt against the orthodox faith’. The annalist notes how subsequently ‘a number apostatised from the Christian faith and embraced the faith of the beast’. The text goes on, however, to chronicle the progressive acquiescence of the conquered people to their new masters, noting how Amr ibn al-‘Āṣ ‘exacted the taxes which had been determined upon but he took none of the property of the churches and he committed no act of spoliation or plunder, and he preserved them throughout all his days.’

Charles, R: The Chronicle of John, Coptic Bishop of Nikiu, Being a History of Egypt before and During the Arab Conquest, translated from Zotenberg’s Edition of the Ethiopic Version. The Text and Translation Society, Philo Press, Amsterdam

Howard-Johnston, J: A Detailed Narrative of the Arab Conquest of Egypt in Howard-Johnston, J: Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp.181-189.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.152-156.

Theophilus of Edessa: Chronicle source

One of a series of short chronologies a work by one Thomas of Edessa, an astrologer who served under the caliph Al-Mahdī (775-785), the so-called ‘Syriac Common Source’ that formed the source for later chroniclers of this period provides more evidence of Jerusalem as a cultic focus. In the entry for 634 the chroniclers using this source describes how ʿUmar entered the Holy City clothed in filthy garments made of camel’s hair, and showing diabolical deceit, he sought the Temple of the Jews, the one built by Solomon, in order to make it a place of worship for his blasphemy. Seeing this, Sophronius said, “Truly this is the abomination of desolation, as Daniel said, standing in a holy place”. For the year 642, the chronicler relates how ʿUmar began to build the Temple in Jerusalem, but the structure would not stand and kept falling down. When he inquired about the cause of this, the Jews said to him, “If you do not remove the cross that is above the church on the Mount of Olives, the structure will not stand.” On account of this advice the cross was removed from there, and thus was their building made stable. For this reason the enemies of Christ took down many crosses.’

Howard-Johnston, J: The Lost History of Theophilus of Edessa and its derivatives in Howard-Johnston, J: Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp.194-236.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.400-409.

Hoyland, R: Theophilus of Edessa’s Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam, Translated Texts for Historians, Vol.57, Liverpool University Press, 2011.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.224-234.

John Bar Penkaye ܟܬܒܐ ܕܪܝܫ ܡܠܐ

Writing in the year 687, The Book of Salient Points is a chronicle of the world in brief form, so as ‘not to get entangled in lengthy narratives, and so lose the thread of forget our purpose … to demonstrate what God has done for us in His grace and what we in our wickedness have presumed to do in opposition to Him’. At the end of the fourteenth chapter the author explains how the conquest occurred: ‘We should not think of the advent (of the children of Hagar) as something ordinary, but as due to divine working. Now when these people came, at God’s command, and took over as it were both kingdoms, not with any war or battle, but in a menial fashion, such as when a brand is rescued out of the fire; not using weapons of war or human means. God put victory into their hands in such a way that the words written concerning them might be fulfilled, namely, ‘One man chased a thousand and two men routed ten thousand’! How, otherwise, could naked men, riding without armour or shield, have been able to win, apart from divine aid, God having called them from the ends of the earth so as to destroy, by them, a sinful kingdom, and to bring low, through them. the proud spirit of the Persians…. Against those who had not ceased in times of peace and prosperity from fighting against their Creator, there was sent a barbarian people who had no pity on them. The fifteenth and last chapter describes the nature of these Arab conquests – ‘robber bands, among whom were also Christians in no small numbers: some belonged to the heretics, while others to us’ – and explains all the famines and plagues as proddings by God for Christians to repent for ‘those who in peace and prosperity did not cease from fighting against their Creator there was sent a barbarian people who had no mercy on them…Bloodshed without reason was their comfort, rule over all was their pleasure, plunder and captives were their desire, and anger and rage were their food’. Their coming is conceived of in Biblical terms as part of God’s plan as a preface to the end of the world, being steered by the ܡܗܕܝܢܘܬܐ (mhaddyānūthā ‘guidance’) to ‘hold to the worship of the One God in accordance with the customs of ancient law’. The author notes how these originally zealously held to the ‘tradition’ (ܡܫܠܡܢܘܬܐ mashlmānūthā) of Muḥammad, but then details how this degenerated into factionalism, leading to the triumph of the Umayyads, where order and justice was restored. His account goes on to detail the rebellion of al-Mukhtār (685-687) and ends with an apocalyptic prediction of the destruction of the Ishmaelites ‘for only one thing is missing for us: the advent of the Deceiver’. Noteworthy is the lack of any reference or awareness of a sacred scripture, as is the case with all the contemporary Christian writings.: none describes him in terms other than as a teacher or a political leader, nor is there any reference to a sacred writing.

Brock, S: North Mesopotamia in the late seventh century: Book XV of John Bar Penkayé’s Rish Melle, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, 9 (1987), 51-75. Includes an English translation.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.194–200 (translation of extracts).

Mingana, A: Sources Syriaques, Vol.1, Book 15. Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1908. Part 2. Syriac text p.143ff; French translation p.172ff. Syriac text and French translation and Index.

Pearse, R: John bar Penkaye, Summary of World History (Rish melle). English translation of Book 15.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.85-107.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.185-201. Translated excerpt.

< 700

Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius ܡܐܡܪܐ ܥܠ ܝܘܒܠܐ ܕܡܿܠܟܐ̈ ܘܥܠ ܚܪܬ ܙܒ̈ܢܐ

This apocalyptic vision, a vaticinia ex eventu, delivered from Mount Sinjar, is attributed to Methodius bishop of Olympus (ob.312 AD) and was likely written in around the year 690, a date that corresponds to a prediction of 70 years in which the Arab kingdom was supposedly to last. It speaks of those who will come, under the four leaders of the Ishmaelites: Desolation, Despoiler, Ruin and Destroyer, who will be ‘destitute of love and robbers and spoilers and the wild and those void of understanding and of the religion of God … who will be servants of That One and their false words will find credence … true men and clerics will be subjected to the punishment of the Ishmaelites … They will blaspheme and say: “There is no deliverer for the Christians”. Then suddenly there will be awakened perdition and calamity and a king of the Greeks will go forth against them in great wrath… and will lay desolation and ruin in the desert of Jethrib and in the habitation of their fathers.’ Those who are left will be able to return, ‘everyone to his land and to the inheritance of his fathers, ‘and there will be peace on earth the like of which had never existed, because it is the last peace of the perfection of the world. And there will be joy upon the entire earth, and men will sit down in great peace and the churches will arise nearby, and cities will be built and priests will be freed from the tax.’ The theme of the apocalyptic section of his chronicle is that if the Byzantine emperor was to hand over his dominion to God at the end of time, the Byzantine Empire itself would last to the final consummation and none of its enemies would ever be able to destroy it. The expectation and hope was that the end of the world was about to begin with the impending fall of the Arabs.

Aerts, W and Kortekaas, G: Die Apokalypse des Pseudo-Methodius: die ältesten griechischen Übersetzungen, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 570, Louvain 1988. Parallel Greek and Latin texts.

Alexander, P and Abrahamse, D (ed): The Byzantine apocalyptic tradition, University of California Press 1985, pp.13-60. English translation and study of the Greek translation.

Bonura, C: When did the Legend of the Last Emperor Originate? A New Look at the Textual Relationship between the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius and the Tiburtine Sibyl, in Viator, vol. 47 no. 3 (Autumn, 2016).

DiTommaso, L: The Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius: Notes on a Recent Edition.

Garstad, B: Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius, An Alexandrian World Chronicle, Harvard University Press, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 14, 2012. Greek and Latin texts with English translation.

Greisiger, L: Ein nubischer Erlöser-König: Kūš in syrischen Apokalypsen des 7. Jahrhunderts. In Sophia G. Vashalomidze, Lutz Greisiger (eds.): Der christliche Orient und seine Umwelt. Gesammelte Studien zu Ehren Jürgen Tubachs anläßlich seines 60. Geburtstages (Studies in Oriental Religions 56). Wiesbaden, 2007.

Grifoni, C and Gantner, C: The Third Latin Recension of the Revelations of Pseudo-Methodius – Introduction and Edition and Gritoni, C: Pseudo-Methodius’ Revelations in the so-called Third Latin Recension, in Wieser, V, Eltschinger, V and Heiss, J: Cultures of Eschatology, Volume 1: Empires and Scriptural Authorities in Medieval Christian, Islamic and Buddhist Communities – Volume 2: Time, Death and Afterlife in Medieval Christian, Islamic and Buddhist Communities. De Gruyter, 2020, pp.194-253.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.263-267.

Livne-Kafri, O: Is There a Reflection of the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius in Muslim Tradition? in Proche-Orient Chrétien 56 (2006): pp.108-119.

Lolos, A: Die Apokalypse des Ps.-Methodius, Beiträge zur klassischen Philologie, Vol. 83, Meisenheim am Glan, 1976.

Martinez, F: Eastern Christian Apocalyptic in the Early Muslim Period: Pseudo-Methodius and Pseudo-Athanasius. Dissertation 1985, pp.2-201. Syriac text and English translation.

Minski, M: The Kebra Nagast and the Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius: A Miaphysite Eschatological Tradition,Jerusalem 2016.

Reinink, G (ed.): Die Syrische Apokalypse des Pseudo-Methodius, vol.1 , Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium,vol. 540 (Lovanii: E. Peeters, 1993), 1993, pp.1-48. Syriac text.

Reinink, G (ed.): Die Syrische Apokalypse des Pseudo-Methodius vol.2 , Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, vol. 541 (Lovanii: E. Peeters, 1993), pp.1-78. German translation.

Reinink, G – Neue Erkentnisse zur Syrischen Textgeschichte des ‘Pseudo-Methodius’ in Hokwerda, H. et al. (eds): Polyphonia Byzantina, Studies in Honour of W. J. Aerts. 1993, pp.85-96.

Shoemaker, S: A Prophet Has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes, A Sourcebook. March 2021, pp.80-84.

The Edessene fragment of Pseudo-Methodius

An abridged and modified version of the Pseudo-Methodius apocalypse extant in a 17th-c manuscript, the text, which scholars date to the 690s, adds that both the Sons of Ishmael and a horde of unclean nations from the north will be defeated in Mecca, that the city of Edessa will remain inviolate, and that Christ’s final victory will follow two reconquests of Jerusalem. The world will then end, and the Last Judgment will commence. The motive for its composition is likely to have been the turmoil accompanying the second Arab civil war and the subsequent consolidation of Umayyad rule under ʻAbd al-Malik. Many Syriac Christians were moved to predict the imminent demise of Arab rule.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.267-270.

Martinez, F: Eastern Christian Apocalyptic in the Early Muslim Period: Pseudo-Methodius and Pseudo-Athanasius. Dissertation 1985, pp.206-228. Syriac text and English translation.

Palmer, A: The Seventh Century in West-Syrian Chronicles, (with S. Brock and R. Hoyland), Liverpool university Press, 1993, pp.243–250. English translation.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.130-138

< 710

Coptic Apocalypse of Pseudo-Athanasius ⲟⲩⲗⲟⲅⲟⲥ ⲉⲁϥⲧⲁⲟⲩⲟϥ ⲡⲉⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲥ

This work, ascribed to the 4th century patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria includes an apocalyptic account of the trials of the faithful, ending with a prediction of the conquest of the Arabs: ‘God will stir up upon the earth of mighty people, numerous as the locusts. This is the fourth beast which the faithful prophet Daniel saw … And that nation will come upon the earth in its final days … That nation will rule over many countries and they will pay a tax to it. It is a brutal nation with no mercy in his heart … Many Christians, Barbarians and people from Basan and Syrians and from all tribes will go and join them in their faith, wanting to become free from the suffering that they will bring up on the earth… Their leader shall live in a city called Damascus, whose interpretation is “the one which rolls down to Hell” … The name of that nation is Saracen, one which is from the Ishmaelites, the son of Hagar, maidservant of Abraham.’ There is a mention of a new coinage, now bearing the name Muḥammad, as the invaders ‘destroy the gold on which there is the image of the cross in order to mint their own gold with the name of The Beast written on it, the number of whose name is 666.’ There is also in this text the first occurrence of the use of the Hijrī calendar, as monks are seized and branded with ‘the date of the rule of Islam … in the year 96 of the Hijra there was anxiety among the monks and anguish among the faithful. If an unbranded monk was found, they brought him before the governor who would order one of his limbs to be cut off.’ The text ends with an eschatological warning that‘when you see the bishops, the priests, the deacons and the superiors of the monasteries rendering assistance to those nations, then know and see that the abomination of desolation, namely, the Antichrist, has approached. Woe to the world in those days!’

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.-282-285.

Martinez, F: Eastern Christian Apocalyptic in the Early Muslim Period: Pseudo-Methodius and Pseudo-Athanasius. Dissertation 1985, pp.285-411 (Coptic and Arabic text) and pp.462-555 (English translation).

Van Lent, J: Réactions coptes au défi de l’Islam: L’Homélie de Théophile d’Alexandrie en l’honneur de Saint Pierre e de Saint Paul in Etudes coptes XII, Quatorzième journée d’études (Rome, 11-13 juin 2009), éd. par A. Boud’hors et C. Louis (Cahiers de la Bibliothèque copte 18), Paris 2013, pp.133-148.

Witte, B: Die Sünde der Priester und Mönche, Koptische Exchatologie des 8. Jahrhunderts, Teil 1: Textausgabe, Oros Verlag, Altenberge 2002. Coptic text and German translation, with extensive study.

Apocalypse of John the Little ܓܠܝܢܐ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ ܙܥܘܪܐ

Composed in the early years of the 700s, this pseudonymous work is part of a collection entitled the Gospel of the Twelve Apostles together with Revelations of each one of them. The Apocalypse of John the Little contains some of the earliest references to Christians converting of Islam, and unlike other apocalypses which emphasized the transitory nature of their conquerors’ rule – in line with the traditional Christian interpretation of Daniel in which the Romans (now the Byzantines) would constitute the world’s final kingdom – it reinterprets Daniel’s four kingdoms as those of the Romans, the Persians, the Medes and the people of the South. As part of what was ‘written on the scrolls what men are to suffer in the last times’ …these people of the South will come in fulfilment of Daniel’s prophesy (XI, 15) that ‘God will bring forth a mighty southern wind’ … A warrior, one whom they will call a prophet, will rise up among them … None will be able to stand before them, because this was commanded of them by the holy one of heaven… They will take all the world’s people into a great captivity. They will pillage them, and all the corners of the world will become slaves. They will impose tribute … the likes of which was never heard …and will especially afflict all who confess Christ our Lord. Because, to the end, they will hate the Lord’s name. They will abolish his covenant, and truth will not be found among them. Rather, they will love evil and adore sin. They will do everything that is hateful in the Lord’s eyes and will be called a defiled people.’ The apocalyptic passage goes on predict their downfall as ‘the Lord will become angry with them, as with Rome, Media, and Persia … and an angel of wrath will descend and kindle evil among them’ in the form of the civil wars of the Fitna, after which ‘the Lord will return the southern wind to the place from which it came, and he will abolish its name and glory.’

Drijvers, Han J.W., Christians, Jews and Muslims in northern Mesopotamia in early Islamic times. The Gospel of the Twelve Apostles and related texts, in The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East. I: Problems in the Literary Source Material. Edited by Cameron, Averil and Conrad, Lawrence Irvin: Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 1. Princeton, NJ: Darwin, 1992, pp.67-74.

Drijvers, Han J.W.: The Gospel of the Twelve Apostles: A Syriac Apocalypse from the Early Islamic Period, in Drijvers, H: History and Religion in Late Antique Syria, Variorum 1994, pp.199-208.

Hoyland, R: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Vol. 13 Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1997, pp.267-270.

Penn, M: When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, pp.146-156.

Rendel-Harris, J: The Gospel of the Twelve Apostles Together with the Apocalypses of Each One of Them, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1900, pp.34-39. Syriac text and English translation.

Greek Daniel (First Vision) – Διήγησις περὶ τῶν ἡμερῶν τοῦ ἀντιχρίστου τὸ πῶς μέλλει γενέσθαι