Is there an influence from 'Wahhābī Salafism' on political Islam? If the reform project advocated by the Muslim Brotherhood may be considered the dominant intellectual matrix of political Islam, since the end of the 1970s a ‘Salafī anti-hegemonic discourse’ has emerged in Saudi Arabia, one that calls for an alternative vision for society and for engaging in a ‘symbolic struggle’ as to how reality is to be constructed and represented.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

DURING THE 1970S Saudi Arabia’s ambition and desire for influence began to surface. The oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 granted Saudi Arabia an unprecedented and unexpected geopolitical weight, and a margin of fiscal capacity that allowed it to implement an influence strategy it had never previously thought to achieve.

In 1979 Saudi Arabia received a painful blow to its influence and religious prestige with the hostage-taking at the Grand Mosque in Mecca.

On November 20th than year more than 200 militants seized control of the Grand Mosque during the reign of King Khālid ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz, and claimed the appearance of the awaited Mahdī. At the time some Islamic currents were beginning to form in a number of Saudi regions and across the Arab world, including some Islamic movements in Syria, but this coincided with the conclusion of the Camp David treaty – the official Arab recognition of the end of the era of war with Israel and its recognition of its right to exist – and the victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, which generated among other Islamic currents a sense of the possibility of repeating what Khomeini did in Iran. Added to that was the image of immorality of the Arab governments and the fear in these at the prospect of future Islamic movements controlling other countries in the region, and the emergence of Islamic states or republics outside of their control.

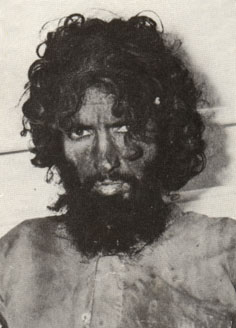

The events at the Grand Mosque began 16 days after the onset of the US embassy hostage in Tehran. Juhaymān al-‘Utaybī, the commander of the operation, justified his attack as a victory scored for the awaited Mahdī, the One who will fill the earth with justice and equity, in place of the current immorality and oppression, and called for the pledging of allegiance to Muḥammad ‘Abdullah al-Qaḥṭānī as caliph of the Muslims, and their imam as the awaited Mahdi.

The Saudi government found itself embarrassed and with its hands tied in the face of this act

After the dawn prayer Juhaymān al-‘Utaybī, with Muḥammad ‘Abdullah al-Qaḥṭānī beside him, announced before the worshipers the emergence of the Mahdī, and demanded that they pledge allegiance to Muḥammad al-Qaḥṭānī as the Mahdī who is to be followed. In the meantime the group took out light weapons hidden in coffins introduced before the time of prayer purporting to contain the bodies of the dead who were to be prayed for in the mosque. They were, instead, packed with weapons and ammunition, and the gunmen were able to close off all the doors and block the outlets of the sanctuary and fortify the interior.

A number of worshipers who were inside the sanctuary were able to perform the dawn prayer before fleeing. As for the rest, many seem to have been forced to comply. Juhaymān delivered a sermon from the minarets of the mosque during the siege broadcast by Arab and international radio stations, which contained a host of accusations against the Saudi ruling family. The Āl Sa‘ūd was held to have deviated from the teachings of the faith and from its principles, and objections were voiced concerning the general lifestyle of the people and how corruption had become rampant.

The echo of these calls continued to reverberate between the mountains of Makka and its neighbourhoods at various times, during which calls were made to the people of Makka and the Saudi special forces that had laid siege to the Grand Mosque to repent and join the militants and pledge allegiance to the Mahdī. The Saudi government found itself embarrassed and with its hands tied in the face of this act.

Before embarking on any military action, a fatwā had to be issued permitting any intervention by force and the use of weapons within the precinct of the Grand Mosque in Mecca to end the siege. The authorities were duly able to obtain the assent of 32 senior scholars to use force against the Juhaymān movement and allow the armed storming of the Grand Mosque.

Two weeks later, the attack began and continued on into the evening. Although the official Saudi narrative was largely fictitious in its claim that it was exclusively the Saudi army that undertook the liberation of the Ḥaram, other accounts have confirmed the fact that foreign countries contributed freeing the Grand Mosque in Makka from the armed group. After the Saudi king issued orders to the Royal Guard to liberate the Ḥaram and rid it of the militants, the operation failed as a result of dogged resistance from the militants. An American document dated November 24, 1979 and addressed to the US State Department, confirms that Saudi Arabia used American pilots to fly over the Ḥaram who participated in inflicting damage to the Grand Mosque in Makka..

Many scholars have described the export of Wahhābī Salafism as ‘the Āl Sa‘ūd religious diplomacy tool’ par excellence

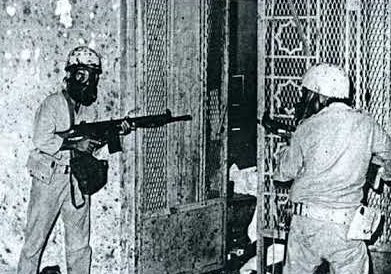

Due to the gravity of the situation following the failure of the first attempt the Saudi leadership drew up a number of plans to liberate the sanctuary, including flooding it with water, then applying electricity to lethally electrocute the rebels. This seemed difficult to achieve given the possibility of a large number of deaths among pilgrims. Under a French official mandate from former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Barril and two of his colleagues of the Group d’intervention de la Gendarmerie (GIGN), all three of whom were among the world’s most famous snipers at the time, headed to Riyadh and met with Saudi King Khālid ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Āl Sa‘ūd and senior military commanders.

In the absence of information on the whereabouts and numbers of the militants, the French military delegation assessed the situation and prepared a plan to liberate the compound. The French plan was based on snipers targeting Al-‘Utaybī and his followers who were located in the upper places of the sanctuary, and forcing them to go down to lower levels. The operation commenced on the morning of December 4, 1979 with the sanctuary being besieged from all sides. Gas was launched into the places where the militants were located, and the operation ended with total control of the sanctuary and the killing of the majority of the rebels and arrest of all the rest.

The operation left nearly 5,000 people dead, most of them civilians and worshippers. One source states that Osama bin Laden commented on the incident by saying:

It would have been possible to solve this crisis without a fight, as sensible people agreed at the time. The resolution of the situation would only have been a matter of time, especially since those in the sanctuary numbered only a few dozen, their weapons were light – mostly hunting rifles – their ammunition supplies were limited and they were besieged. However, the enemy of God did what no other pilgrims before him had ever done, he stubbornly resisted everyone and forced the caterpillar tracks and armoured vehicles into the sanctuary. I still remember the impact of the tracks on the tiles of the sanctuary – lā ḥawla wa-lā quwwata illā bi-Llāh – and people still remember how the minarets were covered in black after being shelled by the tanks. Innā li-Llāh wa-innā ilayhi raji‘ūn!

In order to expand and strengthen its influence and re-establish its religious legitimacy from this painful blow, and in an effort to consolidate its position as a regional power in the Middle East and confront the young Islamic Republic of Iran, whose ‘revolutionary’ principles presaged a danger of penetration into the region, Riyadh relied on the ‘promotion and exporting’ of Wahhābī Salafism to Muslim societies around the world.

A number of non-governmental organizations and transnational Islamic organizations such as the Muslim World League and Saudi institutions have worked to combine preaching with social and humanitarian work, and have invested financially and ideologically in many places across the globe to preach and support a conservative interpretation of Islam, so much so that many scholars have described this practice as ‘the Āl Sa‘ūd religious diplomacy tool’ par excellence.

Suggested Reading

In addition to this so-called soft power strategy, Riyadh also engaged in hard power. For example, it supported armed groups in Afghanistan in their war against the Soviet army in 1979 and exported and disseminated this ‘ideology’ with the support of the ‘first generation’ of jihadists – Afghans and a large number of foreign fighters who, in the name of ‘Islamic Internationalism’ mobilized Afghanistan to defend the Islamic Umma against the Soviet Union. Returning to their country of origin after the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan in 1988 these trained and experienced jihadists actively participated in the spread of Salafī-jihadism.

In this way the spread of Saudi Wahhābī Salafism has had its impact across the globe, and affects the entire Muslim world.

Even so, despite these interactions and mutual influences, there remains a strong distinction between the ‘Islamism’ of the Muslim Brotherhood and that of the Salafists. The attacks of September 11, 2001, also signalled a rupture between the Saudi regime and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Main image: Snapshot taken during the siege of the Grand Mosque at Makka in 1979