Antoine Milot conducted a study on the origin, differences, and predictions of political Islam in the Middle East and North Africa, which I would like to briefly present in this paper.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

MILOT’S CAREER as a French researcher led him to work with many public and private figures in North Africa and the Middle East. His topics of study focused mainly on geopolitical dynamics in the region, and the status of political Islam occupied an important place in his research field.

Critics of political Islam – or ‘Islamism’[1] – are almost unanimous in holding that Islamists are all driven by the need to create a ‘global Islamic caliphate.’ This ranges from the average simple sympathizer of a party that adopts the values of Islam, to the fanatical and extremist jihadist activist. All of them, hypothetically, are obsessed with the establishment of an Islamic state based on a fundamentalist interpretation of the Qur’ān and the Sunna.

But the matter is more complex than that, and one should not overlook the divisions that have been permeating political Islam for over a century. And it was by focusing on these divisions that Milo concluded that there have now developed more recent currents, more hostile projects and divergent agendas. The components of the so-called ‘Islamist’ movements are advancing at different rates and rhythms, and are in structural competition with each other at the local, national and regional levels.

One should not overlook the divisions that have been permeating political Islam for over a century

In North Africa and the Middle East the concept of Islamism is a single concept that crystallizes all expectations. The political current is often simplified as one monolithic bloc, dismissed as a manifestation of ‘social obscurantism’, authoritarian policies and violent activism (jihād).

While these charges have undeniable roots on the ground, many accusations of this nature are highly reductive, since they do not distinguish the different ‘waves’ that make up the Islamic spectrum.

In his work Milot sought to understand the nature of these differences and disparities between the Islamist currents, and noted that the national emergence on the one hand of the Muslim Brotherhood and on the other hand the Salafist current, represents the two main ‘successful’ forms of political Islam in the North African and Middle Eastern region. However, despite their interactions and inter-influences, it now clearly appears that there is now a permanent disconnect between these two poles of Islamism, from an ideological-religious perspective rather than from a political and geopolitical perspective.

But what are the potential dynamics of Islamism existing in North Africa and the Middle East? Are there ideological and religious differences, political divisions and geopolitical rivalries between Salafism and the Muslim Brotherhood?

Historically, the Muslim Brotherhood distinguished itself right from the outset from strict Salafism, as evidenced by their position on ijtihād,[2] but a kind of confusion between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists, persists, especially with regard to how to define their political rivalries. The ‘Arab Spring’ also contributed to highlighting the geopolitical rivalry between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists.

A kind of confusion between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists persists

From the beginning, the Muslim Brotherhood differed from Salafism with respect to ijtihad, irrespective of its actual emergence from what is termed the ‘Salafī reformist current’.

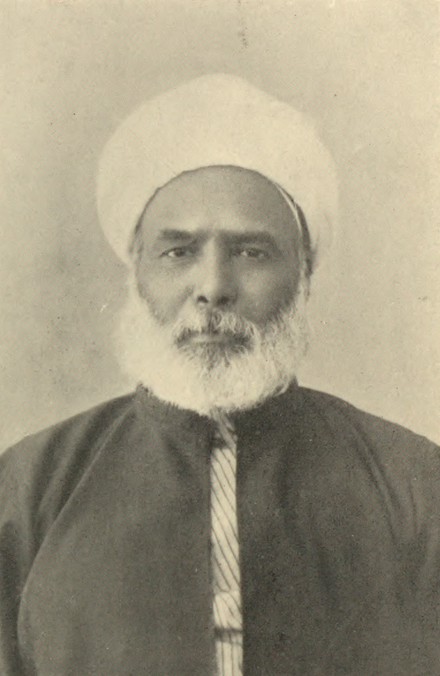

At the end of the nineteenth century, the first movement describing itself as Salafism arose among ‘reformist’ Muslim historians and thinkers, such as the Persian Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, the Egyptian Muḥammad ‘Abduh and the Syrian Rashīd Riḍā. They called for a return to the sources of Islam in order to counter a dual ‘existential threat’: European colonialism and the Ottoman domination. At the time, this Salafī current was elitist, modern and intransigent in its propaganda, hence the early establishment of the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928.

The Muslim Brotherhood aspired to be a continuation of these reformists. Ḥasan al-Bannā’ became editor-in-chief of the Al-Manār newspaper after Rashīd Riḍā’s death in 1935, which indicates the influence and role of reformist Salafists in the late nineteenth century in the emergence of the Muslim Brotherhood, with its assertion that it was Islam that should set the guidelines for society and with its opposition to ‘blind imitation’ of the European model. This is what appears in Ḥasan al-Bannā’ book Memoirs of the Call and the Preacher. They sought to ‘revive’ Islam, and so a special attention was paid to ijtihād.

The Brotherhood remained close to Sufist currents for a long time, but they soon became motivated towards political and social commitments, and in particular objected to the path that was being adopted by Egypt (the Wafd Party).

Suggested Reading

The main guiding principles of the movement were drawn up during the twentieth century: a conservative Islam that adopted the above-mentioned reformist Salafism, a programme for the ‘Islamization’ of society from below through proselytizing based on the social values of Islam, the adoption of Sharī‘a and the condemnation of violence.

[1] ‘Islamism’ generally refers to political Islam. The term originated from the confrontation between Western modernity and Islam, and its origin can be traced back to the eighteenth century with thinkers such as Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhāb (1703-1792) and ‘Wahhābism’, or the later Ḥasan al-Bannā’ (1906-1949), the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood. Both of these advocated an ‘Islamo-political religious system’ that attempted to impose the Sharī‘a in whole or in part as the basic law of a state or group of states. Analysts and researchers have employed the term ‘Islamism’ particularly since the seventies of the last century, in order to avoid using the term ‘fundamentalism. They thereby make a distinction between Islamism and fundamentalism, which more specifically refers to a return to the primary sources of religion (the Salaf). In the case of Islam, fundamentalism may also mean a literal reading of the sacred Text (the Qur’ān). Islamism has been the starting point of many concepts in the Muslim world in thinkers such as Sayyid Quṭb. Some of these concepts served as a springboard for radical and extremist movements, while some also supported the establishment of the Islamic State in Iran after the 1979 Khomeinist revolution. On the other hand, the term ‘Islamism’ has also been used to describe the social, economic and political transformations that took place in the Islamic space between the sixties and seventies of the last century. It is this multiplicity of meanings that is creating some considerable semantic confusion about Islamism. It is clear, however, that Islamism today expresses itself, first and foremost, by a rejection of, or a refraining from, adopting the characteristics of Western modernity that‘Islamism’ seeks to counter, contend with, or even eliminate by force. It is for this reason that, for Muslims described as ‘moderate’, Islamism isassociated with terrorist groups, and is considered to be a deviant and fanatical form of Islam.

[2] See Glossary.