Non-Muslims generally see Islam as a political-religious movement, built entirely on a holy book – the Qur’ān – a book of paramount and fundamental importance for believers. It is the source of everything: the source of belief, of worship and human dealings, the basis of all rituals, the source of Sharī‘a law and the supreme authority to be referred to in cases of disagreement. The Muslim also sees history, the future and the fate of the world through the Qur’ān. Based on it, the rules of behaviour and thought were crystallized, as well as the principles and rules of grammar and rhetoric.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

IN THE QUR’ĀN, the Hebrew Bible is referred to in two different ways: the ‘Book’ and the ‘Torah’. The Torah defines not only the Pentateuch – the five books of Moses – but also the rest of the Hebrew Bible[1] along with post-biblical sources such as the Talmud [2] and the Midrash.[3]

If the reflection of the Hebrew Bible in the Qur’ān is entirely fragmentary, it nevertheless includes many indications of it and features a number of biblical stories and characters. The Hebrew Bible is also important to Islam because Qur’ānic scholars interpret many of its passages to be prophecies about the coming of Muḥammad and the triumph of Islam. In addition, many Muslim commentators question the integrity of the texts of the Hebrew Bible in their Christian and Jewish versions, and that these could have been falsified – on the grounds, in their view, that revelation should contain only God’s words.

The Tanakh is of particular importance to Islam because its contribution, indirectly above all, is crucial. Islam considers it to be one of the sacred texts revealed by God before the Qur’ān, as well as evidence of the Qur’ān’s ‘proof’.

In the Qur’ān, many ‘post-Biblical elements overlap with biblical accounts as if they were part of the Hebrew Bible

The Qur’ān rarely quotes verses verbatim from the Hebrew Bible but gives emended or commented versions, given that the Qur’ān is concerned with the content of what it adopted from it rather than its literal wording. It is as if the recipient is supposed to know the story of the holy book as conveyed by popular oral tradition. In the Qur’ān, many ‘post-Biblical elements – including many of the midrashīm (plural of midrash) – overlap with biblical accounts as if they were part of the Hebrew Bible, while many of the midrashīm’s elements actually do not. The gaps are then filled via exegetical literature and hadith collections. This is particularly the case with the Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’ (‘Tales of the Prophets’) by Ibn Kathīr[4] which provide a richer picture to the Hebrew Bible.

According to the Qur’ān and the Islamic narrative, Adam was a Muslim – that is, one who ‘submitted’ to God, as was Abraham and all of the prophets. A famous hadith asserts that every newborn child is by nature inclined towards this submission to God, that is it is born a Muslim, and that it is only the actions of his parents who make him a Jew, a Christian, a Mazdakian, a Zoroastrian, or otherwise.[5]

There are many memories of Old Testament figures, such as Adam, Noah, Lot, Jacob… And stories such as those of Abel’s burial by his brother Cain, the story of Abraham, a warrior of icons and idols, who survived the flames of fire, stories of Joseph’s rejection of the wishes of his master’s wife “Potiphar”, or the account of the life of Moses, one of the central figures in the Qur’ān.

The Qur’ān also contains biblical concepts such as the Garden of Eden or the Resurrection among other things. The ethics of the Qur’ān, for their part, adopt the statements of the Ten Commandments with some further expansion made to some of them.

In addition to the terms ‘Book’ and ‘Torah’, the Qur’ānic text employs the term zabūr ‘Psalms’[6] – a Qur’ānic designation for the mazāmīr (Hebrew מזמורים mizmōrīm) which refers to a scripture that was independently revealed to David. The Qur’ān also vaguely mentions the ‘books’ (ṣuḥuf or kutub) of Abraham and Moses, or simply the first asfār (Hebrew ספרים sfārīm) without knowing which writings these referred to exactly. The Qur’ānic writings also speak of the ‘People of the Book’, designating Jews and Christians.

Muḥammad and Christ in the Hebrew Bible – ‘announcing the coming of Muḥammad’

According to the Islamic narrative, several verses of the Hebrew Bible predicted the coming of the Prophet Muḥammad and the triumph of Islam. But they are the same passages in the Bible where Jewish or Christian commentators see in them an evocation of the coming of the Messiah, as in a verse from Isaiah IX that mentions ‘a child born’ (…) with the ‘sign of his government on his shoulder’.[7] Muslim scholars consider in this the ‘seal’ of prophecy which, according to Islamic belief, appears specifically on Muḥammad’s shoulder.[8]

The Islamic narrative has interpreted what is mentioned in Isaiah IX as a prior announcement of the coming of the Prophet Muḥammad bearing the seal of prophecy on his shoulder. How, then, did the Christians interpret this passage? The interpretations almost unanimously agree on the following:

Isaiah was speaking of the birth of Jesus, and the Hebrew phrase for to us a child is born signifies a child to be born among us and for us. The phrase the government shall be upon his shoulder signifies Christ with his cross that he carried on his shoulder reigns over the hearts of all those who believe in him.

Many Islamic narratives give Muḥammad a certain ‘messianic dimension’

In Islam, the term al-masīḥ (the Messiah) is attributed specifically to Jesus of Nazareth, or in the form al-masīḥ al-dajjāl (the ‘deceitful Messiah’, or ‘anti-Christ’) in Islam to a demonic figure who foreshadows the end of times Islam. There is mention of the idea of a saviour, which previously had existed among Arab Christians, as it did in Aramaic or Syriac.

For al-Ṭabarī, the Messiah is Jesus who is ‘cleansed of man’s defects and debilities’. Abū ‘Abd Allāh al-Qurṭubī lists quotes 23 views regarding the origin of the word al-masīḥ in his work al-Tadhkira fī Aḥwāl al-Mawtā wa-Umūr al-Ākhira (‘A Reminder of the Conditions of the Dead and the Matters of the Hereafter’) while others mount up fifty opinions.

Even so, many Islamic narratives give Muḥammad a certain ‘messianic dimension’. Thus the Gospel of Barnabas[9] – a manuscript written by a sixteenth-century Spanish Muslim in Italian – retained the title of al-masīḥ exclusively for Muḥammad and the Moriscos made Muḥammad the universal Messiah even though Jesus was the Messiah only to the Israelites. Similarly, the Ahmadiyya community considers Mirza Ghulam Ahmad to be the Messiah and the Mahdī, although this in the Muslim world is but a marginal usage.

The Arabic translation of the Hebrew Bible

While some sources in the Islamic narrative acknowledge that there are literary arguments for the existence of Arabic translations of the Hebrew Bible that date back to the ninth century AD, the evidence is very uncertain. Abū Muḥammad ‘Abd Allāh ibn Muslim ibn Qutayba al-Dīnūrī[10] quoted passages from Genesis and reproduced them in Arabic. According to Ibn al-Nadīm[11] the historian Aḥmad ibn ‘Abd Allāh ibn Salām had translated the entire Hebrew Bible into Arabic, but his work was lost and nothing remains of it. Ibn Ḥazm al-Andalusī’s work Al-Faṣl fī al-Milal wal-Ahwā’ wal-Niḥal (‘On Peoples, Passions and Sects’)[12]contains numerous excerpts from the Hebrew text.

Suggested Reading

Some unfinished publications relative to the Hebrew Bible are attributed to the Nestorian theologian Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq[13] in the ninth century AD and to Yaphet ibn ‘Alī in the tenth century (d. 101 AD). But the most complete translation into Arabic, accompanied by commentaries, was produced by the tenth-century Jewish scholar, Saadia Gaon.[14] It is not known whether Muslims were aware of these translations and whether they saw them.

The integrity and distortion of texts

The Qur’ān is to be considered as a written version of revelation (the word of God – and according to some Muslim scholars the verbatim word) that declares that God is unique; has no companion or partner or rival. Thus, in this strict monotheistic perspective, Muslims understand the Qur’ān to be the ‘last revelation’ – the final revelation come to correct the Jewish and Christian distortions of the first original revelation concerning Adam. Although it borrows many passages from the Hebrew texts, Islam has since its inception contested the integrity of the Hebrew Bible. The Qur’ān strongly censures the Jews, arguing that they have altered their book[15] – that is, they replaced some passages[16] announcing the coming of the Prophet of Islam.

The Qur’ān is referred to as ‘Makkan’ (revealed at Makka) and ‘Madinan’ (revealed at Madina). There are two phases, one with many Biblical expressions and formulas and corresponding to the Makkan period (612 AD-622 AD), the other corresponding to the Madinan period (622 AD-632 AD), during which the rupture occurred between on the one hand the Muslims and on the other hand both Christians and Jews. Verses which raise the issue of corruption, alteration, and distortion directly or explicitly never actually indicate that the text of the Torah (or Bible) has been forged, instead concur more with the authenticity of the Torah and the Gospel. Qur’ānic tafsīrs confirm this, yet ambiguity on this issue still remains for as long as it is not specified exactly where corruption, distortion and alteration has occurred.

Christoph Luxenberg,[17] for his part, asserts that the Qur’ān (the ‘canonical version’) selects from Judeo-Christian texts, while rejecting some manuscripts and scrolls as having been ‘forged’ by scribes. It also sought to decide between different readings of the texts in Aramaic and Hebrew, something which led to a distortion of the meaning of the verses as they were read.

The argument on the falsification of the Bible predates the Qur’ānic text, and it is possible that Muḥammad borrowed it from Christians who had previously used it against the Jews

In fact, when the Massoretes[18] wrote down the text of the Hebrew Bible, they standardised the words and phrasing of the text and imposed a standard recitation that is at odds with the recitation the Qur’ān derived from the Hebrew Bible. However, for the Qur’ān, it was the Jews who changed the meaning of the revealed words, having forgotten part of what was revealed to them and which the Qur’ān in part mentions, while the Christians also forgot part of what was revealed to them. Verse 15 of Sūrat Al-Mā’ida runs:

O People of the Scripture! Now hath Our messenger come unto you, expounding unto you much of that which ye used to hide in the Scripture, and forgiving much. Now hath come unto you light from Allah and plain Scripture.

Christoph Luxenberg concludes that the argument on the falsification of the Bible predates the Qur’ānic text, and it is possible that Muḥammad borrowed it from Christians who had previously used it against the Jews – as evidenced by the quarrel between the Jacobites and the Nestorians on the subject.[19] The traditional Islamic narrative attributes these modifications mainly to ‘Uzayr, a mysterious figure in the Qur’ān whom many Muslim authors recognize as the scribe Ezra mentioned in the Bible[20] held to have erased all evidences regarding Muḥammad’s coming and prophecy, or any descriptions of his or his attributes, or any mention of the triumph of the new religion that humanity will call for.

In Islam, Abraham becomes the original figure for the pure monotheistic believer, before the deviations perpetrated by the Jews and Christians whose sacred books do not reflect, according to the Qur’ān, the purity of the Qur’ānic message. Therefore, for Muslims, the Bible cannot be considered an authentic book.

[1] The ‘Hebrew Bible” refers to the collection of books written in Hebrew and Aramaic which Jews accept as sacred texts. It is also termed the Tanakh. ‘Tanakh’ is an abbreviation in Hebrew letters כ–נ–ת (T-N-Kh) referring to (T) for Torah, (N) for Nevī’īm (‘Prophets’) and (Kh) for Khetūvīm (‘Scriptures’) which together make up the Jewish holy book, and it is the most commonly used term for the Hebrew Bible in the scholarly community. It is also called מִקְרָא Miqrā’ – the ‘reading’.

[2] The Talmud is the central text for rabbinic Judaism and the primary source for Jewish religious law (Halakha) and Jewish theology. Before the modern period, the Talmud formed the central book of cultural life for all Jewish societies and was the foundation of ‘all Jewish thought and hope, and a guide in the daily life’ for Jews. The term Talmud refers to a group of writings called the ‘Babylonian Talmud’, along with an older collection known as the ‘Jerusalem Talmud’. The Talmud consists of: the Mishnah (written around 200 AD) which is a compendium of the oral Torah of rabbinic Judaism, and the Gemara (written around 500 AD) which is an explanatory commentary of the Mishnah that deals with other topics and provides extensive interpretations of the Hebrew Bible.

[3] The Midrash is a collection of ancient commentaries on all parts of the Tanakh organized and categorised differently from one group to another. Each part of a work in the Midrash can be quite short, some of them at times a matter of a few words or a single sentence . Some of the sections of the Midrash are included in the Talmud.

[4] Ibn Kathīr’s Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’ is an encyclopaedic work categorising materials relative to the prophets, collecting together verses that relate to the story of each prophet in a dedicated chapter. These are linked together in tafsīrs and hadiths and related issues.

[5] It is stated in the Ṣaḥīḥs of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, as related by from Abū Hurayra, that the Prophet Muḥammad said: There is none born but is created to his true nature (Islam). It is his parents who make him a Jew or a Christian or a Magian quite as beasts produce their young with their limbs perfect. Do you see anything deficient in them? … ‘The nature made by Allah in which He has created men there is no altering of Allah’s creation; that is the right religion’ (quoting Qur’ān XXX (al-Rūm), 30). See https://sunnah.com/muslim:2658b . The hadith, of course, does not say ‘make him a Muslim’ since the child is born a Muslim. It implies that none other than those already Muslim actually ‘submit’ to Allah.

[6] The Bible, the Old Testament, the Book of Psalms – most of the Psalms were revealed to David, the shepherd, soldier, king and prophet. David organized the service of praise in the Holy of Holies. Only 73 of the body of 150 Psalms are explicitly attributed to David. Many scholars believe that the Book of Psalms was finalized by the Second Temple rulers, although most reflect the official worship of the pre-exilic era.

[7] Isaiah IX, verses 6-7: For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end, on the throne of David and over his kingdom, to establish it and to uphold it with justice and with righteousness from this time forth and forevermore. The zeal of the Lord of hosts will do this.

[8] The Seal of Prophethood is one of the signs and indications of Muḥammad’s Prophethood. It is a red swelling like a dove’s egg, a mass of hairs between the Prophet Muḥammad’s shoulders and nearer to his left shoulder. Some even went so far as to say that it was like a stony mark, or like a black or green mole, on which there inscribed ‘Muḥammad is the Messenger of God’ or ‘move forth for thou art granted victory’ or suchlike things. But none of this was confirmed.

Editor’s note: The issue of whether the term ‘seal of the prophets’ derives from Mani the prophet of Manicheism, who was also referred to in Muslim sources as the ‘Seal of the prophets’, may have more to do with the usage of the seal metaphor by Mani as defining his role as ‘sealing’ in the sense of ‘authenticating’ the prophets that preceded him. This is the way it is used in the Xuāstvānīft, a Uyghur Manichean confession book. (on this see, in the Almuslih Library, Guy Stroumsa’s The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity pp. 87-99). It may also be conjectured that the Qur’ānic phrase khātim al-nabiyyīn ‘the seal of the Prophets’ [Qur’ān XXXIII (al-Aḥzāb) 40] is meant to refer to Muḥammad in the same way, not as finalising the sequence of the prophets but as confirming the message of the prophets, in the way that this is expressed in Qur’ān XXXVII (al-Ṣāffāt), 36-37: And said: Shall we forsake our gods for a mad poet? Nay, but he brought the Truth, and he confirmed those sent (before him).

[9] The Gospel of Barnabas is by an anonymous author and describes the life of Jesus of Nazareth. The two oldest manuscripts, in Italian and Spanish, date from the end of the sixteenth century, but of the Spanish text only an eighteenth-century copy is extant. The Italian manuscript consists of 222 chapters, most of which describe the ministry of Jesus. In many ways, particularly the explicit proclamation of the coming of Muḥammad, it corresponds to the prevailing Muslim idea of the New Testament. Scholars generally consider this Gospel to be a ‘devout forgery’—that is, a document designed to support a late-appearing and false doctrine. Many Muslims do not consider it any more or less authentic than the other Gospels, while some Muslim organizations cite it to support the Islamic conception of Jesus. Jacques Jomier proved that it was the work of counterfeiters or of a Moorish monk who had converted to Islam. According to Henri Corbin the author possessed a great knowledge of Jewish, Christian and Muslim theology. The Gospel of Barnabas may suggest the influence of the Ebionites and developed the theme of the pre-existence of Muḥammad first popularised among Gnostic philosophical mystics before penetrating into more Orthodox circles. For more information on this see: Geneviève Gobillot: ‘Évangiles et Pacte prééternel’ in Mohammed Ali Amir-Moezzi (dir.) Dictionnaire du Coran, éd. Robert Laffont, 2007, pp. 290-291 and 628.

[10] Known as Ibn Qutayba (213 AH / 828 AD – 276 AH / 888 AD), one of the leading lights of the third century AH / ninth century AD, an ‘Abbasid scholar, jurist, critic, philologian and author of many works, the most famous of which are ‘Uyūn al-Akhbār, the Adab al-Kātib and others. He was considered a proponent of the Ahl al-Sunnah wal-Jamā‘a (see Glossary) and used his pen to elevate the status of the Sunnīs and refute the arguments of their opponents.

[11] Ibn al-Nadīm Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq (d. 994 AD, 995 AD or 998 AD) was a historian, biographer, encyclopedist and collector of indexes born in Baghdad. He is the author of the well-known book the Kitāb al-Fihrist which he published in 938 AD. In its introduction he described himself as a collector of all Arabic and non-Arabic books that had been published. Ibn al-Nadīm was the first bibliographer in the Islamic world, in that prior to his time all that existed were books termed ṭabaqāt (‘classes’) that categorised poetry and poets. He was the first to use the Persian word fihrist (‘index’) and introduce it to Arabic. The fihrist is a work in which he collected every book and essay that had been published by his time – works on religion, jurisprudence, law and accounts of famous kings, poets, scientists and thinkers. He stated that he had been working on it since 377 AD. By 385 AD he had passed away, leaving many gaps in the work, which were filled by ‘the Moroccan Vizier’ in (418 AH), but this addendum is no longer extant. In fact, the Fihrist is considered to be the culmination of Arab culture of his time. Ibn al-Nadīm listed 8,360 books by 2,238 authors, including 22 women and 65 translators. Among the areas covered by the Fihrist were the field of linguistics, holy scriptures, the Qur’ānic sciences and religious beliefs.

[12] Ibn Ḥazm al-Andalusī al-Qurṭubī (384 AD / 994 AD – 456 AH / 1064 AD), is considered one of the greatest scholars of Andalusia and after al-Ṭabarī one of the greatest and most prolific Islamic scholars. Al-Faṣl fī al-Milal wal-Ahwā’ wal-Niḥal is a comparative study of religions, sects, and non-Islamic beliefs, and a digest of the opinions of Islamic denominations such as Mu‘tazila, the Jahmiyya, the Qadariyya, the Shī‘a and others (see Glossary). The work is notable for its complete boldness in criticism, its sagacious insights, its discussion and refutation of various ideas. Ibn Ḥazm worked up to 20 years on its composition.

[13] Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq was born in al-Hira c. in 808 AH / 1405 AD and died in Baghdad in 873 AH / 1468 AD. He was an Arab doctor, translator and a lecturer at Baghdad, and was a Nestorian Christian. He served under nine caliphs. He is kown in the West under the Latin name ‘Johannitius’ and with the sobriquet of the ‘Master of Translators’. Around 830 AH / 1426 CE, he was overseer of the translators of the ‘House of Wisdom’ of the Caliph al-Ma’mūn. He then participated in the polemical scholarly debates organized by the Caliph al-Wāthiq (842 AH – 847 AH) and was reknowned for his ethics as a doctor. The caliph Ja‘far al-Mutawakkil asked him, in exchange for a large sum of money, to prepare a poison for him so that he could get rid of one of his enemies. Ḥunayn’s response was that his knowledge and experience only related to what was beneficial, and that he did had studied nothing else. Two things thus prevented him from preparing the deadly poison: his religion and his profession. Considering this an affront, the caliph imprisoned him and threatened him with execution if he continued to refuse to obey the order. But he maintained his position, and the caliph released him and rewarded him with a large sum of money for his moral and professional integrity. About a hundred works, half of which have reached us, are attributed to him and are mostly in manuscript form, since very few of them have been printed. Many were written in Syriac, but almost all that remains are those written in Arabic. What has survived is his response to the Muslim scholar Ibn al-Munajjim who wrote a work entitled Al-Burhān in which he claimed to prove by logic the truth of Muḥammad’s prophethood.

[14] Sa‘īd ibn Yūsuf Abū Ya‘qūb al-Fayyūmī, known as ‘Saadia Gaon’ (268 AH / 882 AD – 330 AH / 942 AD) was an Egyptian Jewish rabbi and philosopher. He was influenced by scholastic theology and the Mu‘tazila doctrine. He defended the legitimacy of prophecy and the oneness of God, and refused to believe in magicians and astrologers. He was the first important Jewish figure to write extensively in Arabic.

[15] Qur’ān V (al-Mā’ida), 13: And because of their breaking their covenant, We have cursed them and made hard their hearts. They change words from their context and forget a part of that whereof they were admonished. Thou wilt not cease to discover treachery from all save a few of them. But bear with them and pardon them. Lo! Allah loveth the kindly.

[16] Qur’ān VII (al-A‘rāf), 162: But those of them who did wrong changed the word which had been told them for another saying, and We sent down upon them a pestilence from heaven for their wrongdoing.

[17] ‘Christoph Luxenberg’ is the pseudonym of the author of the book A Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran. This book asserted that the language of the early writings of the Qur’ān was not exclusively Arabic, as the classical commentators postulated, but was rooted in the Syriac language of the Makkan tribe of Quraysh in the seventh century AD, a tribe which was associated in ancient times with the establishment of the religion of Islam. Luxenberg’s hypothesis was that the Syriac language that was prevalent throughout the Middle East during the early period of Islam was the language of culture, and the liturgy of Christianity, and had a profound influence on the biblical formation, meaning of the contents of the Qur’ān.

Editor’s note: On this, see the Almuslih articles: An Aramaic and Syriac reading of the Qur’ān and Syriac and Aramaic origins of the Qur’ān.The book is available in the Almuslih Library here.

[18] The Masoretes are those who preserved the מסוֹרָה masōra, the ‘tradition’ of the text and were known as the בַּעֲלֵי הַמָּסוֹרָה Baʿălēy Hammāsōrā ‘The Masters of the Tradition’ – the tradition or handing on of the faithful textual form of the Hebrew Bible, as well as the nuances of how it was to be pronounced, at a time when the languages in which the Bible was written had long died out. Many schools maintained different versions of it, but in the ninth century AD the system of Aaron ben Asher from Tiberias became the standard. The masōra comprises a system of critical notes on the external form of the biblical text, designed to preserve it accurately not only in the way words are spelled but also how they are enunciated and pronounced in pause. An authorised version of the text, that is, one considered reliable within Judaism, is called a ‘Masoretic’ text. It was also widely used as a basis for the translation of the Old Testament in the Protestant and later Catholic Bibles.

[19] The Jacobites, a term attributed to the Syriac Bishop Ya‘qūb al-Barādi‘ī, followed the doctrine that Christ had one nature but two essences, the one divine and the second human but both united. Ya‘qūb al-Barādi‘ī, who lived in the sixth century, was one of the most active bishops in defending the doctrine of one nature (monophysitism). Their communities were dispersed over Egypt, Nubia and Abyssinia. Nestorianism is named after Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, who opposed the teaching of the Council of Ephesus (431 AD) concerning the status of the Virgin Mary as theotokos, ‘’Mother of God’ and preferred to call her ‘Mother of Christ’. His belief was widely spread in Mosul, Iraq and Persia. The Jacobites believed that Christ was God, and that God and man were united in one nature, Christ; the Nestorians argued that Christ had two distinct natures: a theological nature and a human nature, although the two communities also differed in other details.

[20] Ezra (in the Greek Septuagint the Hebrew עזרא ‘Ezrā Is rendered as Ἔσδρας – Esdras) is known as ‘Ezra the scribe’. According to the Hebrew Bible, he was a descendant of Seraiah the last high priest who served in the First Temple, and a relative of Joshua, the first High Priest of the Second Temple. He returned from Babylonian exile and reintroduced the Torah to Jerusalem. Some authors see the name ‘Uzayr as a distortion of ‘Azāzīl which corresponds to the word ‘Satan’ or the Egyptian god Osiris. The historian of early Islam Gordon Newby proposed an association the character of Enoch. See Meir Bar-Asher, article ‘Uzayr, in Dictionnaire du Coran, éd. Robert Laffont, 2007, pp. 892-894.

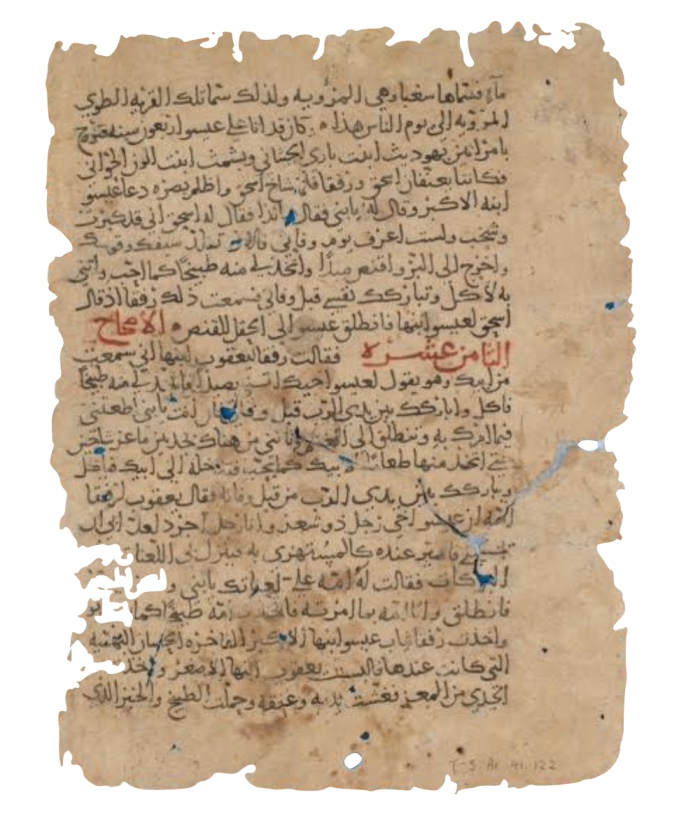

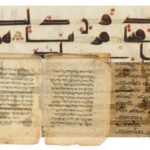

Main image: Arabic text of Genesis XXVI:15 to XXVII:17 from the Cairo Genizah, copied before 963 AD.

Mānī šlīḫā d-Īšō‘ mešiḫā (‘Mani the Apostle of Jesus Christ’). Possibly Mani’s actual private seal.