The student of the Qur’ān will be confronted with the following facts that we discussed in our previous articles. The first of these is that the scribes of the Qur’ān, with the exception of a few cases,[1] did not care to mention the time, place or names of people. The second is that the Qur’ān evolved and that during this development elements were added or removed from it, and sometimes many of its parts underwent distortion.

BY NAFI SHABOU

THIS IS CONFIRMED by the work of scholars and researchers on the distortion of the Qur’ān, and it is from the Epistle of ‘Abd al-Masīḥ al-Kindī to Abdullah al-Hāshimī during the era of Al-Ma’mūn (the Abbasid era) that we learn the truth of forgery, of distortion, of the additions and the manipulation of Qur’ānic texts. The publication of this forbidden Epistle is one of the most important ancient documents that testifies to the fact that the earliest (Christian) Qur’ān had become distorted.[2]

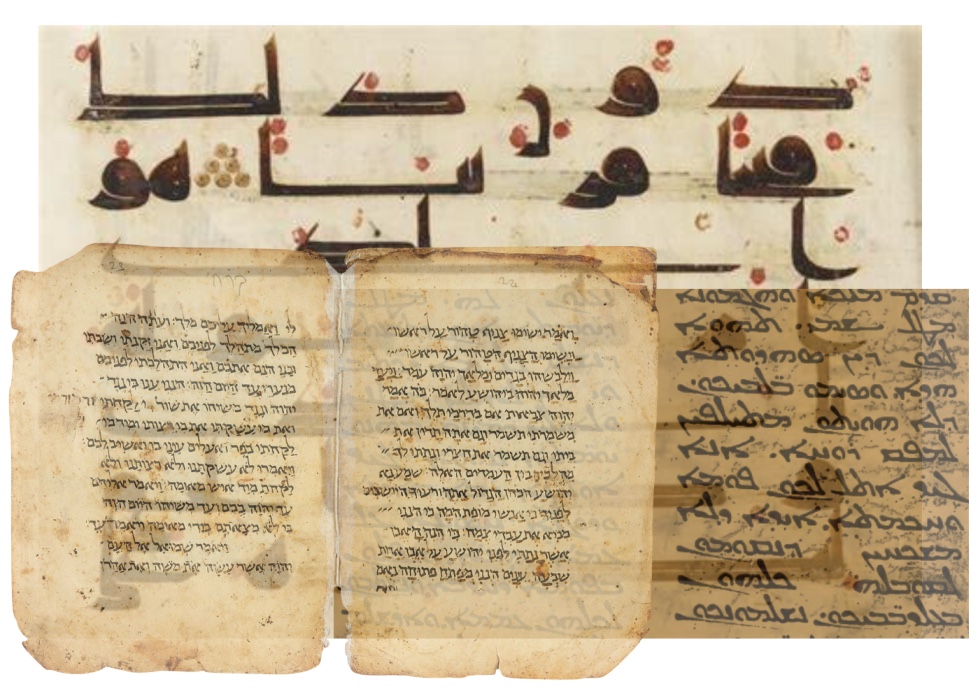

The third fact, the subject of this present article, is this: the plurality of authors and sources of the Qur’ān. The writings of those who translated for the Qur’ān were lifted from many different sources, in particular from the Jewish Torah (the Old Testament of the Christians) and from apocryphal Jewish and Christian works. Materials for this book were also taken from Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Mazdakism, Arianism, Ebionite Christianity and many other sources.

The writings of those who translated for the Qur’ān were lifted from many different sources

Who, then, are the authors of the Qur’ān as given in Islamic works? Later Islamic sources indicate the names of some candidates as authors:

… such as the priest Waraqa ibn Nawfal, the monk Baḥīra, the rabbi Abdullah ibn Salām who converted to Islam before Muḥammad’s death, the rabbi Ka‘b al-Aḥbār who converted to Islam after Muḥammad died, Wahb ibn Munabbih (also a Judaeo-Christian), and Salmān al-Farsī who was condemned by the Magi and subsequently met with monks and priests and then became Muslim after becoming acquainted with Muḥammad (cf the marginalia to Qur’ān XVI, verse 103).[3] Zayd ibn Thābit was the writer of the Revelation and the one in charge of the committee for the collection of the Qur’ān. He was a Jew, according to the testimony of Ibn Mas‘ūd. For Ibn Mas‘ūd was asked: “Do you not recite according to the reading of Zayd?” To which he replied: “What have I to do with Zayd and Zayd’s reading? I have taken seventy sūras from the mouth of the Messenger of Allah himself, whereas Zayd ibn Thābit is a Jew who sports two dhu’ābs” (the braided peyot, the sidelocks of the Jews).[4] This does not mean that these are the ones who wrote the Qur’ān, but it is possible that the information contained in the Qur’ān had been lifted at various stages, and its meanings and its drafting was made by ‘the Messenger of the Arabs’. This means that the Qur’ān is not dependent on a single author, but on a plurality of authors.[5]

Imam al-Bukhārī in his Ṣaḥīḥ narrated from ‘Abd al-‘Azīz ibn Ṣuhaiy, from Anas:

There was a Christian who embraced Islam and read Sūrat al-Baqara and Sūrat Al-‘Imrān, and he used to write (the revelations) for the Prophet. Later on he returned to Christianity again and he used to say: “Muḥammad knows nothing but what I have written for him.” Then Allah caused him to die, and the people buried him, but in the morning they saw that the earth had thrown his body out. They said, “This is the act of Muhammad and his Companions.” … They dug the grave for him as deep as they could, but in the morning they again saw that the earth had thrown his body out. So they believed that what had befallen him was not done by human beings and had to leave him thrown (on the ground).[6]

The historian Jawād ‘Alī says in his book A detailed history of the Arabs before Islam:

It is stated in the Ṭabaqāt Ibn Sa‘d that Muḥammad “went out with Maysara the slave boy of Khadīja until they came to Bosra in the Levant. At the market at Bosra they took shade under a tree near the hermitage of a monk named Nestorius (an alternative name for the monk Baḥīra). The monk looked on Maysara whom he previously knew, and said: O Maysara, who is this who has settled down under this tree… None but a prophet ever sat under this tree.” The chroniclers mentioned the name of the priest Ibn Sā‘ida al-Ayādī, a public preacher at the ‘Ukāẓ marketplace. Muḥammad loved his speeches and stated: “No matter how much I do forget, I will never forget him at the ‘Ukāẓ market, standing atop a red camel preaching.” To this Ibn Sā‘ida is attributed the phrase: “Nay, but He is One God, neither begotten nor begetting”. This account coincides in meaning with the text in Sūrat al-Ikhlāṣ: He begetteth not nor was begotten. And there is none comparable unto Him.[7]

The accounts speak of a Nestorian monk who cured Muḥammad of a severe ophthalmia in his eyes. In addition to the Christian ‘Uthmān ibn al-Ḥuwayrith of the Asad tribe, and the monk ‘Adās al-Nīnawī, Khadīja consulted him about the convulsions he suffered when the revelation came to Muḥammad, at which he said to her:

O Khadīja, the devil may have appeared to the slave and showed him things. Take this book of mine and take it to your friend. If he is mad, he will depart from him, and if he is from God, he will not harm him.

Ibn Isḥāq’s sources (references) vary as to their authenticity and reliability. Hishām ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Sā’ib al-Kalbī was also one who took information from among the People of the Book, and who imported for the Muslims the Isrā’īliyyāt[8] and the genealogy of the Torah. There are others as well who took materials from the People of the Book, but listing their names here would take us away from the heart of our subject. So I only mention these two men due to their conspicuous impact upon those who came after them with respect to the Isrā’īliyyāt and the genealogy of the Torah.

The odd thing is that Orientalists have neglected these resources and have only addressed a few of them

As for the sayings attributed to Ibn Abbās relating to the Torah, these must be handled with in a cautious and deeply critical manner. Comparison should be made with what is stated in the books of the Torah and other Jewish works, and the chain of authorities that narrate these sayings and attribute them to him should be the subject of critical evaluation.

Jawād ‘Alī makes a further admission when he adds:

To date, no researcher has drawn attention to this subject. I hope, therefore, that scholars will attentively give their opinion on this, and to similar statements attributed to other Companions and Followers,[9] so that our judgment in such matters will be studious and scientific.

Concerning Ka‘b al-Aḥbār, Jawād ‘Alī notes:

It was not known that Ka‘b al-Aḥbār composed or wrote anything. What was known about him was that he used to conduct sessions in the mosque in which he talked to people using the Torah. He would sometimes read from it and expound it to them. However, al-Hamdānī mentioned that he had authored books and that the people of Sa‘da had inherited these books and narrated from them. Ka‘b was a Himyarite Jew from the Arab tribe of Dhū Ra‘īn, he had read the Torah, the Gospel, the Psalms, and the Furqān,[10] and was a polymath.

The odd thing is that Orientalists, known for their studiousness and keenness to take note of everything reported about an incident, have nevertheless neglected these resources mentioned and have only addressed a few of them. Foremost among those narrating pre-Islamic news are: ‘Ubayd ibn Shariya and Muḥammad ibn al-Sā’ib al-Kalbī, his son Abū al-Mundhir Hishām ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Sā’ib al-Kalbī, and others. Some of these, such as ‘Ubayd ibn Shariya, Ka‘b al-Aḥbār, Wahb ibn Munabbih were peddlers of legends and myths. Samar took from Jewish myths, and these, and others like them, are the source of the Isrā’īliyyāt in Islam.

Suggested Reading

Wahb relates stories about the Christians of Najrān and the tortures inflicted upon them by Dhū Nuwās, and the story of the monk Femion is identical to Christian tales. It was related that Wahb would make use of books, and that his brother Humām ibn Munabbih used to purchase books for his brother. He may have derived his accounts of some matters related to Christianity, such as the birth and life of Christ, from these sources. It was also narrated that ‘Ubayd ibn Shariya was from a class of storytellers, not of the level of chroniclers, and thus had a proclivity to activities that would spare him condemnation and satisfy a need: tales of the Jews and things related to people in the past that were mentioned in the Qur’ān – for which the early Muslims needed someone to talk about such stories and personalities. Ibn Isḥāq’s narrative is a mixture of Isrā’īliyyāt, tales from ancient Yemen and other materials possibly developed or invented by others before him, or which he took from word of mouth, such as the multifarious poems and verses attributed to the Followers and others. He adopted names taken from the Torah just as they are pronounced in Hebrew, which suggests that they were taken from a Jewish source.

Dr. Jawād ‘Alī adds an important note for students of Qur’ānic origins sources and the Prophet’s biography:

I would like to draw scholars’ attention to the importance of the Wahb ibn Munabbih narrations and reports with respect to those aiming to study the Biblical and Talmudic studies of that era, since there are many passages that Wahb or others claim to have composed, while they are readings from translations of the Torah and from other divine books. If, after comparing them with the texts of the Torah, the Talmud, the Mishna, and other Jewish works, it can be proven that they are indeed from those books, and that they were translated correctly, then we will have obtained some (not most) of the ancient templates for passages in those books that may usefully lead us to still earlier translations. They may also help us to identify the cultural aspects of the Arabs of that era, the era preceding Islam or the era contemporary with the emergence of Islam.

Dr. Jawād ‘Alī provides the name of a man who inserted religious stories for the Muslims:

This is Tamīm ibn ’Aws ibn Khārija al-Dārī who stated that he became Muslim in the ninth year of the Hijra, and that he had been a Christian, and that he met the Prophet, to whom told the story of Al-Jassāsa and Al-Dajjāl.[11] He stated that he was minded towards monasticism and behaved like a monk even after his conversion to Islam … He used to relate tales in the mosque of the Prophet and was thus the first in Islam to do so. He recounted that he was the first to light the lamp in the mosque… However, we cannot rule out the possibility that he confused Christian tales with Arab myths. He was a Christian who listened to the sayings of church preachers, learnt from them, and applied what he learned in Islam.[12]

Our aim here, as the major historian Jawād ‘Alī also purposed, is to prove that most of the religious Qur’ānic texts derive from Judaeo-Christian sources – that is, from the Torah, the Gospel, from Jewish works such as the Mishna and the Talmud, and from apocryphal Gospels and Christian heresies.

[1] See Nafi Shabou: The Qur’ān according to critical research – 3.

[2] See Nafi Shabou: The Qur’ān according to critical research – 6.

[3] Qur’ān XVI (al-Naḥl), 103: And certainly We know that they say: Only a mortal teaches him. The tongue of him whom they reproach is barbarous, and this is clear Arabic tongue.

[4] Cf. Ibn Mas‘ūd’s hadith: According to whose recitation do you want me to recite? Because I recited seventy-odd Surahs to the Messenger of Allah [SAW] when Zaid had two braids, and was playing with the other boys. https://sunnah.com/nasai:5063 (Ed.)

[5] Dr. Sāmī ‘Iwaḍ al-Deeb, القرآن الكريم (see the work here in the Almuslih Library).

[6] https://sunnah.com/bukhari:3617

[7] Qur’ān CXII (al-Ikhlāṣ), 3-4.

[8] Isrā’īliyyāt (‘Israelisms’, ‘Judaisms’) refers to narratives assumed to have been taken into the hadith from earlier Jewish folklore. The term can also be extended to cover the genre of Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’ (‘Tales of the Prophets’). See Glossary: ‘Isrā’īliyyāt’and the Almuslih article:The meaning of the term ‘Isra’iliyyat’. (Ed.)

[9] The ‘Followers’ (Tābi‘ūn) are the generation of Muslims who were born after the death of the Prophet Muḥammad but who were nevertheless contemporaries of the Sahāba (‘Companions’). (Ed.)

[10] Another word for Qur’ān, commonly understood by Muslims as the ‘divider’ or ‘criterion’ between Right and Wrong. The 25th sūra of the Qur’ān is entitled Al-Furqān. (Ed.)

[11] Al-Dajjāl (or Al-Masīḥ al-Dajjāl, the ‘Deceitful Messiah’) is the Anti-Christ, an evil figure in Islamic eschatology who will pretend to be the promised Messiah and later claim to be God, appearing before the Day of Judgement. The term likely derives from Christian Syriac eschatology which features the ܡܫܝܚܐ ܕܕܓܠܘܬܐ mšīḥā d-daggālūtā the ‘pseudo-Christ’, the ‘false Messiah’. Al-Jassāsa is al-Dajjāl’s spy. Many of Tamīm al-Dārī’s stories related in the hadith include those which featured the end of the world, the Dajjāl beasts and the coming of the Antichrist. (Ed.)

[12] Jawād ‘Alī, المفصل في تاريخ العرب (‘A detailed history of the Arabs before Islam’), p.128.

On this essay read the earlier sections: Part One; Part Two; Part Three; Part Four; Part Five, Part Six; Part Seven; Part Eight; Part Nine, Part Ten