In The History of the Qur’ān the Orientalist scholar Theodor Nöldeke hinted at the existence of distortion in the Qur’ān in a section entitled: ‘The Revelation revealed to Muḥammad was not preserved in the Qur’ān’.

BY NAFI SHABOU

WE THEN FIND HIM declaring the existence of distortion in the article ‘Qur’ān’ for the Encyclopaedia Islamica, where he states: ‘there is no doubt that there are paragraphs in the Qur’ān that have been lost’. In the article ‘Qur’ān’ in the Encyclopaedia Britannica the issue of distortion in the Qur’ān is confirmed: ‘The Qur’ān is not complete in all its parts…. It seems that Nöldeke has contributed strongly to consolidating the question of distortion among orientalist thinkers; he opened up for others the way towards a truly scientific study on the subject of the distortion of the Qur’ānic text’.

If we proceed from an assumption that the Qur’ān is immune to distortion, then one would obviously need to dispense with this type of reading. Accordingly the studies of the German Orientalist Nöldeke in The History of the Qur’ān has not been distributed in the Arab world nor translated into Arabic.

The language of the Qur’ān is not a language for communication, and whether for the illiterate or the scholar it is difficult to understand

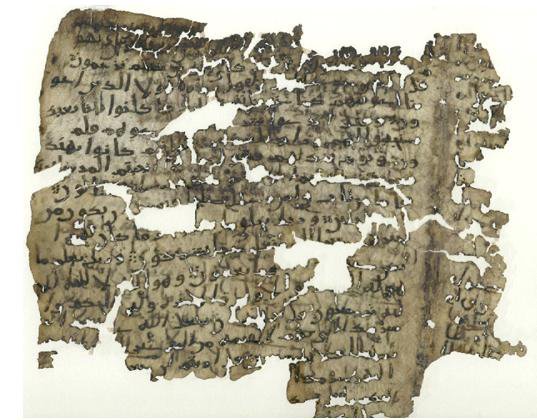

The discovery of a large number of Qur’ānic manuscripts in 1972 during the restoration of the Great Mosque in Ṣan‘ā’ – and which incuded texts dating back to the seventh century AD – represented an important opportunity for Qur’ānic philology. This is especially so since these copies reveal some differences to the canonical text in terms of the order of the sūras and the vocalisation of the letters. To the best of my knowledge no serious Arabic study of these manuscripts exists. Some excerpts, however, have been published in Western journals.

Ancient manuscripts of the Qur’ānic text appear without vocalisation and pointing for consonants and it is difficult today to determine just when the dots were first added, so that ب (b) could be distinguished from ت (t) or ث(th). The same applies to ا (ā) and ي (ī ) and their late appearance in writing. Luxenberg states that:

We do not know precisely how and in what specific circumstances the laws of vocalisation were established due to the contradictory evidences we have in this respect.

Due to its antiquated language, its many allusions, its repeated phrases, and its many contradictory components, the Qur’ān comes across as difficult to understand, and so it is left to commentators and interpreters to separate one possible meaning from other to understand what is meant. Whether it was spread by the sword or the power of meaning and content, the result is the same: the language of the Qur’ān is not a language for communication, and whether for the illiterate or the scholar it is difficult to understand and use as a means for communication. A translation of the Qur’ān into the vernacular dialects of the various Arab countries is very urgent, and there is no room for any doubt on that (see Muṣṭafā Ṣafwān’s book: Why the Arab World is Not Free [1]). Thus, the reader has room to think when presented with concepts and intellectual frames of reference that are contradictory in content, or far from his own reality and the time he is living in. However, even if these translations existed, they would not be enough to solve the problem of the meanings, sources and purposes of the Qur’ānic text for, as Maarouf al-Ruṣāfī says:

The Qur’ān has condemned itself: through its contradictions, distortions, deletions, additions and meaningless phrases, and words that are not worthy of God to speak.

An example of this is the word nikāḥ – a strange incomprehensible and confused word, beyond the capacity of many to grasp.[2] Indeed, it is the object of all manner of disagreements and disputes. No book in the world presents the same level of controversy and disputation as does the Qur’ān. It neither maintains any historical sequence nor evidences any style even remotely close to any method. It is uncoordinated and unreliable.

The Qur’ān has condemned itself: through its contradictions, distortions, deletions, additions and meaningless phrases

Concerning the abrogating and abrogated verses of the Qur’ān, Maarouf al-Ruṣāfī cites the following from the work Al-Itqān fī Tafsīr al-Qur’ān:

The Al-Itqān, when talking about the abrogating and abrogated, relates how Ibn ‘Umar had said, “None of you should say that he has full knowledge of the Qur’ān; how could he know what full knowledge is! So much of the Qur’ān has been lost! Let him say instead: “I have taken of the Qur’ān that which there still is.” This means that ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān left out much of the Qur’ān (i.e. omitted many of the Qur’ānic passages).[3]

In addition, Muslims differ on how to read the Qur’ān. Muslim shaykhs recognise that the issue of abrogating and abrogated verses is a disaster, since about 62% of the Qur’ān is abrogated by other Qur’ānic sūras. The Qur’ān is classified by Muslim scholars into two parts. The first part consists of muḥkamāt (‘decisive’, ‘definite’) verses – that is, verses that do not need to be explained because a muḥkam passage is one that is free of anything that impugns a meaning or is ambiguous, and is ‘reasonable as to its meaning’.

The second part consists of verses that that are mutashābih (‘similar’), that is, words of ambiguous meaning that are difficult to define and distinguish. The mutashābih verse, according to Ibn ‘Abbās, is one ‘which the Muslim believes in but knowledge of which lies with Allah alone’. One should note that it is the mutashābih verses that predominate in the Qur’ān.

Muslim shaykhs recognise that the issue of abrogating and abrogated verses is a disaster, since about 62% of the Qur’ān is abrogated

Since the time of ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān, who burned the Qur’ān, a kind of dissent has existed among Muslims concerning how to read the Qur’ān. Some of them held to the reading the Qur’ān as according to ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib, others held to the reading the Qur’ān according to Ibn Mas‘ūd, while still others held to the second century hijrī reading of Abū ibn Kalb, and even others who maintained the reading of the desert-dwelling Arabs. Due to these different readings the present Qur’ānic text has undergone expansion, shortening, distortion and alteration.[4]

‘Abbās ‘Abd al-Nūr in his work My ordeal with the Qur’ān and with God in the Qur’ān[5] writes:

Truly, the Qur’ān is not amongst the secrets of the gods. It is not connected in any way to divine inspiration that would take it outside historical trends. It is purely a human achievement that complies with human principles. Like all human efforts, it is subject to strength and weakness, accuracy and error, agreement and contradiction, cohesion and disarray, consistency and inconsistency, originality and imitation, depth and superficiality, lucidity and brittleness.

You will hardly come across one page where ideas correlate or flow in a connected sequence, or follow one another

Elsewhere in his book the writer summarises how in his study of the Qur’ān he found

contradictions, generalisations, pompous rhetoric, and facetious phrases that have no meaning. The grammatical and stylistic errors that the classical scholars were at their wits’ end trying to find explanations for. And other mistakes, both of scientific and historical natures … The Qur’ān is full of rhetorical explosive charges and verbal bombs that create such an extreme uproar that ears almost become deaf. But after deep analysis, and despite what it contains of sweetness and charm and alluring beauty, it becomes clear that it is pale, emaciated, with little content and lacking substance, like bubbles in the air, or radiating beams of light from fireworks that soon extinguish and fall to the ground, spent, leaving behind pitch darkness.

Even the doggerel of soothsayers is better—a thousand times better, in fact—than many of the Qur’ānic verses that are of nonsensical language and so stuffed full of fairy tales that the Qur’ānic commentators (and, strangely, some Mu’tazilites) have had to become past masters in dealing with it and defending it.[6]

The writer draws an ominous conclusion that every Muslim ought to grasp, which is that anyone reading the Qur’ān cannot possibly know “who is the one who misguides people? Who is the one who makes evil deeds seem good?”

What is the difference between them? The God of the Qur’ān seduces people and leads people astray, and “misguidance, making bad seem good, seduction and temptation are all evil attributes shared by God and Iblees, according to the text of the Qur’ān. So what is the difference between them? Are they not just two sides of the same coin?”

Suggested Reading

The Qur’ān has condemned itself: through its contradictions, distortions, deletions, additions and meaningless phrases, and ‘words that are not worthy of God to speak’. As Abbās ‘Abd al-Nūr concludes:

That which it contains of contradictions goes beyond the limit of “a lot.” Nay, it is the centre of every disparity and contradiction! The amount of disparities and contradictions in any other book in the world has not yet reached the level of the Qur’ān.

[1] In his work Why the Arab World is Not Free (لماذا ليس العالم العربيّ حرّا) Muṣṭafā Ṣafwān reveals the structures of tyranny and analyses the mechanisms that prop it up, mechanisms that are not only political, but also social, cultural and linguistic. One of the most prominent components of the structures of tyranny that this work addresses is the relationship between language and writing, and how these link to the powers of tyranny, and to the cultural unconscious as something similar to the individual unconscious. All these act to consolidate the tyrannical relationship between the ruler and the people. (Ed.)

[2] The word nikāḥ has caused the commentators some embarrassment over the centuries, since it appears to waver between ‘marriage contract’ and ‘sexual intercourse’. An example of this is where it occurs at Qur’ān IV (al-Nisā’), 22: And marry not woman whom your fathers married, except what has already passed; this surely is indecent and hateful, and it is an evil way. The confusion is illustrated by the elaborate explanation given on the website Islam Q&A: which explains the verse as saying ‘that it is forbidden for a person to marry a woman with whom his father did the marriage contract but did not consummate the marriage with her, and that it is forbidden for him to marry a woman with whom his father had intercourse but did not do the marriage contract with her’. (Ed.)

[3] The work Al-Itqān fī Tafsīr al-Qur’ān is by Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (c.1445-1505 AD). Immediately after this passage al-Suyūṭī goes on to list many instances of lost or suppressed verses. See, in the Almuslih Library, Al-Itqān fī Tafsīr al-Qur’ān (tr. Muneer Fareed) pp.12ff of the section on Nasīkh and Mansūkh (Electronic pages pp.60ff). (Ed.)

[4] See Maarouf al-Ruṣāfī, الشخصية المحمدية (‘The Muḥammadan Personality’).

[5] Read ‘Abbās ‘Abd al-Nūr’s work My Ordeal with the Qur’ān here. (Ed.)

[6] ‘Abbās ‘Abd al-Nūr also adds the following: “It is as though it is a bolt of lightning, glistening with fury, which then fizzles out as though it never shone” (a line from a poem by Ibn Sina). (Ed.)

On this essay read the earlier sections: Part One; Part Two; Part Three; Part Four; Part Five