Costi Bendaly the author of الله والشر والمصير (‘God, Evil and Destiny’) says in the margin of chapter VI, p. 231 of this work: “A few years after writing these lines, I published an interview with Muḥammad Ṭalbānī, the great Tunisian thinker and historian, and one of the founders of the University of Tunis – a believing and practising Muslim, an expert in Islamic studies boldly fighting for an open Islam, renewed by its return to the Qur’ānic sources (Syriac-Christianity)”.

BY NAFI SHABOU

IN THIS INTERVIEW, conducted in 1988 by the Parisian journal L’Actualité Religieuse he said the following:

“Prayer is one of the five pillars of Islam, and it begins with Al-Fātiḥa, the sūra that opens the Qur’ān with the phrase: In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.” Muḥammad Ṭalbānī added: “Al-Fātiḥa is the key to reading the Qur’ān; those who lost this key read the Qur’ān as if it were a book of hatred, while it is in fact a book of love. They betray the spark that God placed in them and they betray God.” When he was asked at the end of the interview: “You are a lover of the Qur’ān, are you reading the same book as the those who react in paroxysms?” He replied: “Yes, but I read it with this key to reading Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful, whereas those (the generality of Muslims) do not want to take up this key, and cannot not see it”.

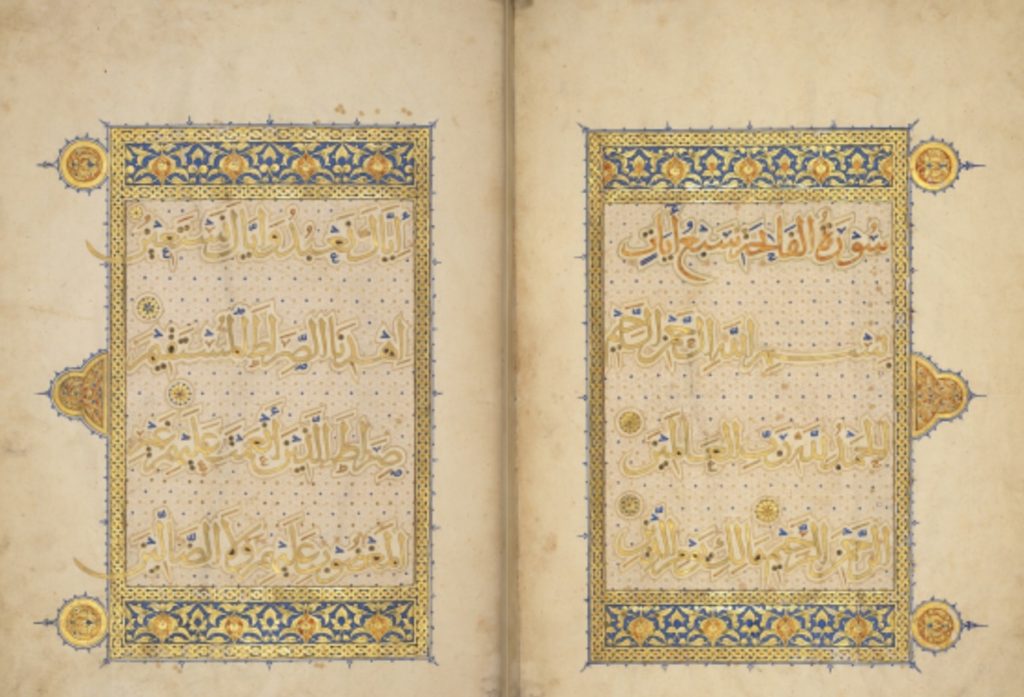

When we turn to Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa, which is the first sūra in the Qur’ān, we discover that Muslim scholars have interpreted it according to a jurisprudence that was not based on the roots of this sūra, which we discover is from a Syriac Christian source: a prayer recited by Christians before Islam. The evidence is numerous and has been published on many sites.

A pre-Islamic, Syriac reading of the Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa would be (with the Arabic text in brackets):

ܒܫܡ ܐܠܗܐ ܪܚܡܢܐ ܪܚܝܡܐ B’shem Ālāhā rakhmānā rakhīmā

(B-Ism Allāh al-raḥmān al-raḥīm)

In the name of God the merciful the beloved

ܚܡܕ ܠܐܠܗܐ ܪܒ ܥܠܡܝܢ

Khamd [1] le-Ālāhā rabb ‘ālmīn

(al-ḥamd li Allāh rabb al-‘ālamīn)

Praise be to God the Master of the ages

ܪܚܡܢܐ ܪܚܝܡܐ rakhmānā rakhīmā

(al-raḥmān al-raḥīm)

The merciful the beloved

ܡܠܟ ܝܘܡ ܕܝܢܐ mlek yawm dīnā

(mālik yawm al-Dīn)

King of the Day of Judgement

ܐܝܟܐ ܐܢܬ ܢܥܒܕ aykā (aṉ)t [2] ne‘bed

(iyyāka na‘bud)

Wheresoever, Thee we worship

ܘ ܐܝܟܐ ܐܢܬ ܢܬܥܢܡ wa-ayka (aṉ)t net‘enem

(wa-iyyāk nasta‘īn)

And wheresoever, Thee we ask for succour

ܐܗܕܐ ܠܢ ܠܐܣܛܪܛܐ ܕܡܬܬܩܢܝܢ ahdā lan le-esṭrāṭā dhe-meththeqenīn

(ihdi-nā al-ṣirāṭ al-mustaqīm)

Guide us to the way of the upright ones

ܐܣܛܪܛܐ ܕܗܢܘܢ ܕܐܢܥܡܬ ܥܠܝܗܘܢ esṭrāṭā dhe-hānōn de-an‘emt ‘alayhōn

(ṣirāṭ alladhīna an‘amta ‘alayhim)

The path of those whom you have favoured.

The Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa (‘in the name of God’) is still written at the beginning in the Syriac way: bismi ‘Llāh and not bi-ismi ‘Llāh. This was how the Syriac speakers wrote and pronounced their language, and therefore the original form was b’shem Ālāhā which is how the Arabs used it in the Qur’ān, and still do. The Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa is not part of the Qur’an[3], but has been taken over from a Syriac prayer of supplication.

The Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa (‘in the name of God’) is still written at the beginning in the Syriac way

Let us turn now to some Muslim interpretations of Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa:

-

- In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

- Praise be to Allah, Lord of the Worlds,

- The Beneficent, the Merciful.

- Master of the Day of Judgment,

- Thee (alone) we worship; Thee (alone) we ask for help.

- Show us the straight path,

- The path of those whom Thou hast favoured; Not the (path) of those who earn Thine anger nor of those who go astray.

This is al-Ṭabarī’s interpretation on the word bism:

The Messenger of Allah said: The mother handed over ‘Īsā ibn Maryam to the scribes in order that they may instruct him. One teacher said to him: “Write bism”. ‘Īsā replied “What is bism?” The teacher said: “I do not know!” To which ‘Īsā replied: “The b stands for God’s effulgence (bahā’); the s stands for His radiance (sanā’); the m stands for His Kingdom (mamlaka).

My own comment is that this bism goes back to the Syriac b’shem, meaning ‘in the name of”, rather than as interpreted by al-Ṭabarī and others. Of the whole Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa here what interests us are verses 6 and 7 and the ‘path’ – ṣirāṭ – that is mentioned there. This is a Syriac word meaning ‘way’, ‘road’,[4] but it is the interpretation of the verse 7 that has proved disastrous, since Muslim scholars have interpreted it according to their belief-system and not according to way it is used in the Syriac prayer.

The path of those whom Thou hast favoured; Not the (path) of those who earn Thine anger nor of those who go astray.

In the Simplified Encyclopaedia of the Qur’ān the following is given:

Ṣirāṭ means the path granted them by the angels, the prophets, the sincere ones, the martyrs and righteous, other than those against whom Thou hast been angered, those who have deviated from the way of truth and righteousness, the ignorant ones that are far off the right path, followers of heretical sects and faiths other than Islam (i.e. the Jews and the Christians) and immoral people and hypocrites.

In one of al-Ṭabarī’s responses to a question, it states:

Who are those who have earned the anger, the ones whom the most praiseworthy God has ordered us to shun? It was said in a hadith that: ‘Aḥmad ibn al-Walīd al-Ramlī related from ‘Abdullah ibn Ja’far al-Ruqqī, from Sufyān ibn ‘Uyayna, from Ismā‘īl ibn Abī Khālid, from al-Sha’bī, that ‘Udayy ibn Ḥātim said: “The Messenger of Allah (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) said: ‘Those who have earned the anger are the Jews. For the Jews are considered to be the children of apes and pigs according to the perverse interpretation of Muslim scholars.[5]

The online site IslamWeb states the following:

When describing the Jews God Almighty made reference to His anger with them, that Worse is the case of him whom Allah hath cursed [Qur’ān V (al-Mā ‘ida), 60]. And He also said: They have incurred anger upon anger [Qur’ān II (al-Baqara), 90]. And when describing the Christians as misguided He said: follow not the vain desires of folk who erred of old and led many astray [Qur’ān V (al-Mā ‘ida), 77].

Muslim scholars have interpreted this verse according to their belief-system and not according to way it is used in the Syriac prayer

This is what Muslims repeat in all their prayers day and night: a supplication to God to curse those with whom He is angry – the Jews and the errant Christians. As evidence for this we may also cite the ṣaḥīḥ hadith recorded by al-Bukhārī and Muslim and others, that runs:

The Muslims will fight against the Jews, until a Jew will hide himself behind a stone or a tree, and the stone or the tree will say: ‘O Muslim, there is a Jew behind me. Come and kill him’.[6]

Some contemporary Muslim researchers want to interpret verse 7 of Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa in a way that differs from the classical commentators of the early centuries of Islam. In one of his published articles the writer Anas Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ wrote about how this sūra was being interpreted:

As for what I saw in most of the works on tafsīr … that those who have earned His anger are the Jews and that the errant ones are the Christians – there is nothing in the Book of God to justify or confirm this. It is an interpretation that entirely opposes and contradicts the spirit, essence and content of the Holy Qur’ān. It has nothing at all to do with the truth. Jews and Christians are adherents to monotheistic heavenly books, just like us. Allah sent them prophets and messengers (peace be upon them) just as to us. Among them are believers and disbelievers, in this respect we are not different from them at all.[7]

Suggested Reading

I agree with the above writer that the majority of Muslim commentators have deviated from the context of Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa, which is originally a Christian prayer, as we mentioned above. How could it be that a Christian would therefore curse his Christian brother? This prayer has nothing to do with the Jews or with the Christians. We do not know where this interpretation of Muslim scholars came from, since there is no Christian or Jewish name in Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa for Muslim commentators to refer to.

[1] The root kh-m-d (‘praise’) exists in Aramaic ( חמד ), but according to R. Payne Smith’s Thesaurus Syriacus the root was not used by the Syrians (p.1302). More commonly the term used was sh-bh-kh, related to the Arabic ṣ-b-ḥ (as in ṣubḥān) (Ed.)

[2] The first letter (-a-) is elided and the second letter (-n-) is unpronounced. (Ed.)

[3] On this see the Almuslih article The Qur’ānic text – Hypothesis 3. (Ed.)

[4] The Arabic ṣirāṭ is a rendition of the Syriac word ܐܣܛܪܛܐ esṭrāṭā and the term originally comes from the Latin (via) strata (‘paved’ road).

[5] The text in al-Ṭabarī’s commentary is here.

[6] For the text of this hadith, see here.

[7] See his article (in Arabic) here.

Main image: the Sūrat Al-Fātiḥa, the opening chapter of the Qur’ān, from an illuminated text commissioned by the Mamluk sultan Rukn al-Dīn Baybars (1223-1277). British Library Add MS 22406.