3. Al-Fatiha confirms the devotional function of the Qur'an There is a question raised by some, according to what Al-Qurtubi relates, about whether Surat Al-Fatiha – the opening sura of the Qur’an – is actually a part of the Qur’an. For there are those who hold that if it were part of the Qur’an “Abdullah ibn Mas‘ud would have confirmed its presence in his Qur’an.”[1] Is it merely a supplication for its opening and a prayer seeking blessing before proceeding with the recitation of the Qur’an? There are many reasons to doubt this.

BY SAID NACHID

FIRSTLY, THE SURA BEARS the name Al-Fatiha, or ‘the Opening’ of the Book, but it is a name that is not derived from any of the words contained within the sura, which in this respect sets it apart from all other suras. The name instead refers to its description as an opening, and therefore subsequent to the completion of the arrangement of all the suras.

Secondly, we usually end the recitation of Al-Fatiha with the word Amin. And this word, albeit not written but orally pronounced, likely bears the possibility that it is merely a supplication for a blessing and an act of worship.

Thirdly, it is clear that the order of the suras was largely, though not always, subject to the criterion of length – whereby the long suras were placed first, with the shortest suras placed last. In this way, placing the Surat Al-Fatiha at the beginning of the Qur’an appears to be a departure from the rule governing the arrangement, if the text constituted a sura like the rest of the suras.

Fourthly, the Surat Al-Fatiha differs from the rhetorical structure governing most of the other suras of the Meccan Qur’an. This sura does not address a specific person or persons, nor does it refer to anyone specific. On the other hand, the rest of the other suras of the Meccan Qur’an manifest at least one of one of the following aspects:

Either they speak to the Prophet using a verb of command:

Say, He is God, one … Say, I seek refuge in the Lord of people … Say, I seek refuge in the Lord of the daybreak … Arise and warn … Read in the name of Your Lord…

He frowned and turned away … Did he not find you an orphan and sheltered you …

or they tell us about a specific person or persons:

May Abu Lahab’s hands perish … for the protection of Quraish …

or they address a specific group:

Rivalry in worldly increase distracteth you …

In comparison, the Surat Al-Fatiha appears to be a pure supplication without any imperative verbs, without a specific addressee, and without any declarative sentences – as if, in the end, it is simply a devotional prayer to the divinity.

However, no matter how legitimate such observations and questions may be, this does not necessarily provide a single, unique hypothesis such as the sura may be fabricated or inserted into the Qur’an. Rather, there is another hypothesis that is more appropriate.

That is, that the Al-Fatiha may not be a sura like the rest of the usual suras of the Qur’an, but at the same time it is also not to be considered a sura lying outside, or on the margins, of the Qur’an. Instead it may constitute a supra-Qur’anic sura. Or more clearly, ‘the mother of the Qur’an’ as the Messenger of Islam said about it.

As Abu Sa‘id ibn Al-Mu‘alla reported:

I was praying, and the Prophet called me, but I did not answer him. I said: “O Messenger of God, I was praying”. He said: “Did not God say: ‘Respond to God and the Messenger when he calls you’?” Then he said: “Shall I not teach you the greatest sura in the Qur’an?” before leaving the mosque. So he took my hand, and as we were about to leave, I said: “O Messenger of God, you said ‘Shall I not teach you the greatest sura of the Qur’an?’” And he said: “Praise be to God, Lord of the Worlds – this is the ‘seven ones that are recited’[2] and the ‘Great Qur’an’ which was given to me.” [3]

As for the word al-mathani (‘recited ones’), which the ancients differed as to how it was to be understood, the martyr Mahmoud Muhammad Taha[4] attempted to provide an approximate meaning:

“The significance of al-mathani is that it has two meanings – a distant meaning known only to our Lord, and a meaning revealed to us.” [5]

Put simply, we can talk of a recondite Lordly meaning and an approachable, textual meaning. This is how we can ascertain, once again, that not all verses of the Qur’an are of the same importance, specificity and precision. There are verses that are more definitive (muhkamat) and unambiguous,[6] and verses that are superior, or more appropriately, there is a devotional sura of seven verses that constitutes ‘the Mother of the Qur’an,’ in the sense of being the greatest of all there is in it, and thus ‘the Great Qur’an’.

It is noticeable that the Surat Al-Fatiha, which does not address a specific person and does not refer to anyone in particular, has a purely devotional function. It takes the form of a divine prayer, without which any other prayer is not valid. As such, its introductory or supra-Qur’anic status supports the devotional function of the rest of the suras and verses of the Qur’an.

Suggested Reading

Restoring the Holy Qur’an to its purely devotional function would serve to rid it of all the ‘magical’ uses that have turned it into a mythical means for solving all the problems of politics, power, economics, industry, money, agriculture, fishing – even problems of health and medicines, and so on.

Nor is it the function of the Holy Qur’an to establish states, found institutions or enact laws. Just as it is not a function of the Qur’an to preoccupy itself with issues of politics, economics, science and knowledge. The function of the Qur’an is for it to be worshipped, and emotional inspiration to be drawn from it – such as mercy, wisdom, love and so on.

As for those imperative verbs, these are commands specific to a time, a place, and to the context of their revelation. We are therefore not continually being commanded by it.

[1] Al-Qurtubi, ، الجامع لأحكام القرآن، تحقيق محمد ابراهيم الحفناوي، دار الحديث، القاهرة، الطبعة الثانية 1996 ، ص: 131، 132.

[2] The Surat Al-Fatiha numbers seven verses: “In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful – All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds – The Beneficent, the Merciful – Master of the Day of Judgment – Thee do we serve and Thee do we beseech for help – Keep us on the right path – The path of those upon whom Thou hast bestowed favours. Not (the path) of those upon whom Thy wrath is brought down, nor of those who go astray.”

[3] Sahih al-Bukhari, المجلد الثالث، منشورات محمد علي بيضون، دار الكتب العلمية، بيروت، طبعة جديدة بدون تاريخ، كتاب تفسير القرآن، ص : 173. . Al-Qurtubi, الجامع لأحكام القرآن، تحقيق محمد ابراهيم الحفناوي، دار الحديث، القاهرة، الطبعة الثانية 1996،ص: 125. Ibn Kathir, تفسير القرآن العظيم، كتب هوامشه وضبطه حسين بن ابراهيم زهران، دار الفكر، بيروت، 1994، المجلد الأول، ص : 16.

[4] Mahmoud Muhammad Taha was a modernizing scholar who was executed by the Sudanese regime in 1985 on charges of apostasy. He had developed what he called the ‘Second Message of Islam’, which postulated that the verses of the Qur’an revealed in Madina were appropriate only to their time but that the verses revealed in Makka represented Islam as an ideal and universal religion (Ed.)

[5] Mahmoud Muhammad Taha, نحو مشروع مستقبلي للإسلام، المركز الثقافي العربي (بيروت) ودار قرطاس (الكويت) الطبعة الأولى 2002، ص:168.

[6] Cf. Qur’an III (Al ‘Imran), 7: “He it is Who has revealed the Book to you; some of its verses are decisive, they are the basis of the Book, and others are allegorical.“

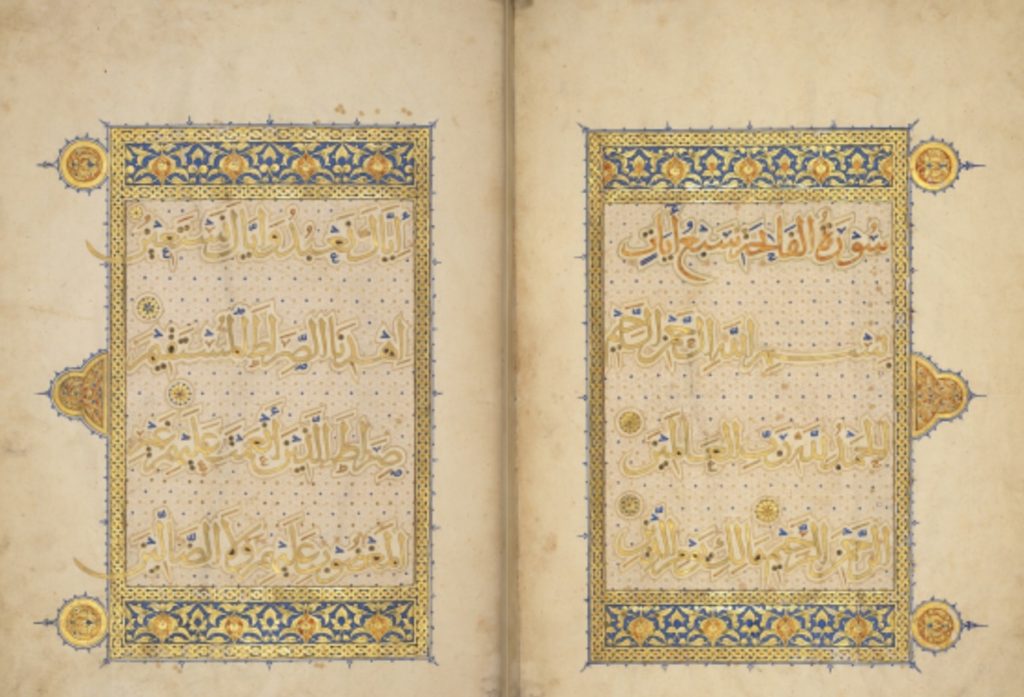

Main image: Qur’ān I (Surat al-Fatiha) 1-7 – from an illuminated Qur’ān commissioned by the Mamluk sultan Rukn al-Dīn Baybars (1223-1277). British Library Add MS 22406.