The month of Ramaḍān is the ninth month in the Islamic Hijri calendar and follows the month of Sha‘bān. Muslims attach a special place to Ramaḍān since it is the month of fasting – the fourth pillar of Islam – and during which Muslims abstain from the lusts of the abdomen and the vulva, that is from eating, drinking and having sexual relations during a specific period that extends from dawn to sunset.

ACCORDING TO THE official Islamic narrative, fasting in the month of Ramaḍān was imposed during the second year of the Hijra (corresponding to 624 AD). This is confirmed by Imam al-Nawawī in his Al-Majmū‘ (6/250) where he says:

The Messenger of Allah (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) observed the fast of Ramaḍān for nine years, since it was imposed in the month of Sha‘bān in the second year of the Hijra, and the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) died in the month of Rabī‘ al-Awwal in the eleventh year of the Hijra.

Fasting is clearly one of the most important elements in the religions of the ancient East, especially the pre-Islamic religions of Judaism and Christianity with, for example, the Jewish Yom Kippur and Christian Lent). History, however, also acknowledges the existence of other religions that adopted the practice of fasting and made it a fundamental act of worship and a basis for theology and doctrine.

History acknowledges the existence of other religions that adopted the practice of fasting

The Sabaean Mandaeans

History books agree on the fact that by 200 AD Sabaeanism in southern Iraq was fully fledged religion. The Sabaeans believe in the ‘Great Living One’ as one creator of the universe and of Man (cf. the Ginza Rabba[1] the holy book of the Sabaeans). The Mandaean religion has Babylonian-Aramaic and Judeo-Christian elements at its core, but most of its beliefs are dominated by the Gnostic view of existence. The Sabaeans believe, among other things, in the necessity of washing and purification, in paying zakāh, praying three times a day and also in the obligation to fast for thirty separate days. This is confirmed by Ibn al-Nadīm’s work al-Fihrist, p. 443:

They have obligations for fastings: thirty days, beginning with the eighth day following the conjunction of Ādhār (March); also nine other [days], beginning with the ninth day from (after) the conjunction of Kānūn al-Awwal (December); and seven other days, beginning with the eighth following [the conjunction of] Shubāṭ (February). These are the most important of them [the fasts].[2]

The Manichaeans

Mani, the Babylonian messenger and ‘Seal of the Prophets’,[3] was born in 216 AD. Mani was educated in an environment of Mandaean influences and elements, and when he was twelve years old he received his first inspiration through a revelation. Manichaeism, in general, is a compromise blend of ancient religions of Persia (the most important of which is Zoroastrianism, albeit separated from it) and Christianity, within a general and comprehensive Gnostic framework. Among many things, Mani enforced abstinence from sexual intercourse, including during marriage, and recommended his followers to pray, give zakāh, and fast for a full month each year. This is confirmed by Geo Widengren’s Mani and Manichaeism (one of the most reliable sources on Manichaeism), p.98:

The Elect had to fast on two days, Sunday as well as Monday, these being the two sacred week-days. In addition there were more extensive periods of fasting, particularly during an entire month prior to the greatest religious festivity of the year, the Feast of Bēma. Presumably this month of fasting provide d the model for the Koranic fast-month of Ramadān.

Suggested Reading

The author later (p.103) explains the circumstances of the Manichaean Feast of Bēma:

Something needs to be said first about the festival at which this meal took place. It was the so-called Bēma Feast which was celebrated at the end of the twelfth or Manichaean fasting month. The focus of it was the remembrance of Mani’s death, and the founder was invisibly present. [4]

In addition, a number of Muslim historians (Ibn al-Nadīm, al-Hamadhānī, al-Bīrūnī and al-Shahrastānī, for example) emphasize how the Sabaeans and Manichaeans were forerunners with regard to fasting for a month, for prayer, for the zakāh tithe, the cleansing from ritual impurity (janāba), supplication to the Truth (al-Ḥaqq), and the forbidding of murder, adultery and lying. It is therefore clear that two of the most important religions of the Fertile Crescent, that of Mandaeans and Manichaeans, served noticeably as a mediator, or an interactive bridge, that enabled the transmission of a set of ideas and beliefs to the emerging and expanding Islamic religion.

[1] The Ginza Rabba (the ‘Great Treasury’), composed in eastern Aramaic, dates from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD and is the longest and the most important holy scripture of Mandaeism. It is composed of two parts: the Right Ginza (eighteen tractates that cover a variety of themes and topics) and the Left Ginza (three tractates focussing on the fate of the soul after death). (Ed).

[2] The English translation text of this passage is taken from Bayard Dodge, The Fihrist of al-Nadim, A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture, (Two Volumes), Columbia University Press 1970, Vol. 1 Chapter IX, Section One, p.747. (Ed).

[3] Editor’s note: The issue of whether the term ‘seal of the prophets’ derives from Mani the prophet of Manicheism, who was also referred to in Muslim sources as the ‘Seal of the prophets’, may have more to do with the usage of the seal metaphor by Mani as defining his role as ‘sealing’ in the sense of ‘authenticating’ the prophets that preceded him. This is the way it is used in the Xuāstvānīft, a Uyghur Manichean confession book. (On this see, in the Almuslih Library, Guy Stroumsa’s The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity pp. 87-99). It may also be conjectured that the Qur’ānic phrase khātim al-nabiyyīn ‘the seal of the Prophets’ [Qur’ān XXXIII (al-Aḥzāb) 40] is meant to refer to Muḥammad in the same way, not as finalising the sequence of the prophets but as confirming the message of the prophets, in the way that this is expressed in Qur’ān XXXVII (al-Ṣāffāt), 36-37: And said: Shall we forsake our gods for a mad poet? Nay, but he brought the Truth, and he confirmed those sent (before him).

[4] See Geo Widengren’s work in the Almuslih Library here.

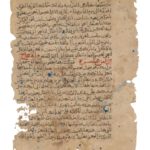

Main image: Rock crystal seal stone with figures in late Parthian style, with a Syriac inscription: ܡܐܢܝ ܫܠܝܚܐ ܕܝܫܘܥ ܡܫܝܚܐ Mānī šlīḫā d-Īšō‘ mešiḫā (‘Mani the Apostle of Jesus Christ’). Possibly Mani’s actual private seal.