These facts about the history of religions help schools pupils and students understand the historical formation of religious phenomena. It blocks the road to blind religious conviction, which is the legitimised mother of fanaticism, extremism, and religious violence. This is the royal path towards a moderate religiosity and an enlightened faith, one that paves the way for a dialogue of religions and cultures which provides today an alternative to wars between religions and cultures. Few people who study the comparative history of religions fail to recognize all religions as equal, since their structure is the same and their origins the same. They have evolved from each other through cultural cross-pollination.

EVERY DISCIPLINE in religious phenomenology can shed a revealing light on one or more religious phenomena. For example, religious sociology teaches new generations that religion is a social phenomenon, and as a whole it is a social phenomenon and therefore a subject for scientific research and analysis. It shows how evolution in society forces religion to adapt to society, and not the other way around. That is, historical developments modify or abrogate the provisions of religious texts. When social actors refuse to adapt it to historical developments, they turn religion into a stagnant phenomenon, that is, they turn it into an obstacle that impedes the historical development of the community of its believers. This is what happened to Islam centuries ago. It also teaches the believer how to play two roles, the role of the believer and the role of the researcher. As a believer it is his when he prays to dissolve in the text, that is. to identify with it; as a researcher he is not to identify with the text but rather take a neutral stance towards it in order to make objective research possible.

This is what we find, for example, with the French philosopher Paul Ricœur. I once asked this French biologist how he reconciled his knowledge with his faith. He replied:

When I enter the church, I leave my knowledge in the dressing room, and when I enter the laboratory, I leave my faith in the dressing room.

This is a model of a Muslim believer which can be reproduced by studying Islam with the sciences of religious phenomenology. In Judaism and Christianity a distinction is made between the religion of faith as a private domain of ritual practice, and the religion of history as a public domain of scholarly inquiry and research. Religious reform can bring about this distinction in Islam as well. It is a stage necessary to attain for the rationalization of Islam and, accordingly, for inculcating rationality in Islamic societies that have become mired in delirium, so that we can at least understand that we are a delirious nation.

The primary reason for the delirium was perhaps the shock of modernity, which the collective psychological personality was unable to absorb

The primary reason for this delirium was perhaps the shock of modernity, which the collective psychological personality was unable to absorb. A violent shock, according to psychiatry, causes the traumatized to turn from neurosis into psychosis. The Psychoanalyst Fatḥī Ben Salāma attributes this collective delirium to what Dr. ‘Abd al-Sabour Shaheen called ‘the contradiction between the Qur’ān and science.’ This delirium is only likely to get worse.

What is to be done?

We need a collective psychological analysis sponsored by a courageous religious reform that separates the Qur’ān from science. This is what Shaykh Mitwallī Al-Shaʽarāwī achieved in his book The Miracle of the Qur’ān, where he writes:

Those who say that the Qur’ān did not come as a book of knowledge are correct. Because it is a book that came to teach me religious rulings and did not come to teach me geography, chemistry or natural science.

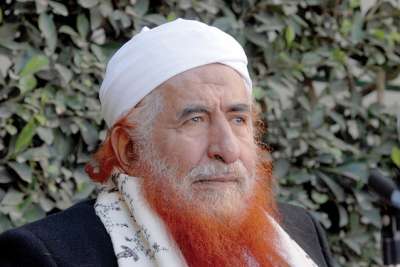

These words deserve to be written with golden ink and learnt by our children right from elementary school, so as to heal the likes of ‘Abd al-Majīd al-Zindānī at the ‘University of Faith’ from a clinical delirium that led him to claim to have discovered from the Qur’ān a cure for AIDS, a claim that doctors in Yemen refused to recognise.

Religious sociology

Religious sociology teaches young people how to analyze religious teachings and texts in relation to the behavior of religious people and the extent of the impact – positive or negative – of these upon them, what are the actual or imaginary needs that they respond to, and how social actors employ religion and for what purpose in any place or time. Such an understanding helps develop religious conduct and direct it towards the private sphere, that is, the family, the religious association and the mosque, so that the public sphere remains open to the practice of values common to all citizens irrespective of faith or sect. These common values are the universal values of human rights produced by the human mind for the human mind.

Religious sociology also teaches students that secularism is the only possible way out of this impasse

Religious sociology teaches us that the religious text does not speak for itself, but rather through the agency of social actors motivated by their own material and political interests or by their own delusions. We thus find that a verse or a hadith is interpreted by each group in accordance with its own political or religious beliefs. It also teaches students that religion is innately conservative and opposes renewal, and is therefore in constant conflict with religious, intellectual, scientific, literary and artistic renewal. It is enough for us to remember the hadith:

“Every new thing is an innovation, and every innovation is a misguidance, and every misguidance is in the fire.”[1]

Religious sociology also teaches students that secularism is the only possible way out of this impasse, so that religion is for God and the homeland is for all, as Saad Zaghloul said.

Religious anthropology

Religious anthropology teaches our students that religious texts are the building blocks of the cultural climate in which they emerged. They are therefore relative and change with changes in people’s sensitivities, lifestyle and mentalities, so they become dated, that is, transcended by time. The texts, especially those relating to transactions and settlements, thus become historically and symbolically significant. This applies to Islamic jurisprudence, legal personal status, and corporal punishments, the application of which has become a scandal and even a crime in the era of a human rights culture that preserves dignity, imposes the inviolability of one’s body, and recognizes a list of rights unprecedented in human history, rights such as the freedom of belief, that is the freedom to change religion, and freedom of conscience, that is, the freedom not to adopt any religion, and the freedom of thought and expression untrammeled by any religious supervision. How can Iran or Saudi Arabia, for example, apply the penalty of stoning, when the civilized countries have abrogated even a prison sentence for adultery? The abrogation includes the government of Muslim Turkey, which abrogated the death penalty and the penalty of adultery and recognized the right of a Muslim to change his religion or not to adopt any religion.

Is it not a scandal that the Supreme Sharīʻa Court in Saudi Arabia refused in 2008 to annul the marriage of a 58-year-old adult with an eight-year-old girl, on the pretext that the Prophet married ‘Ā’isha at the age of nine? The mother of the scandals is that Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arab countries, with the exception of Tunisia and Morocco, remain so far without a modern personal status law that prohibits marriage, child rape, polygamy, unilateral divorce, and disparity in testimony and inheritance? If Islam today is isolated and in conflict with the world and with an ever-growing segment of Muslims themselves, it is because it has not yet adapted itself to the realities of the world in which it lives.

Suggested Reading

The maẓālim courts that misogynistic jurists inflicted on women several centuries ago, today no longer have any anthropological justification in the world in which we live, the world in which a culture of human rights has acquired – in the collective consciousness of humanity and in the consciousness of an increasing segment of Muslims themselves – the legitimacy and sanctity of a religion. And I hope that the reformer King of Saudi Arabia will save both Islam and the Saudi people from the curse of applying legal corporal punishments that distort the image of Islam in the world.

In the name of science, I direct a warm appeal to him to lift the ban on archaeological excavations in the Hijaz, (especially in Mecca and Medina, which are forbidden to foreign researchers), for scientific purposes aimed at uncovering antiquities remaining from pre-Islamic and post-Islamic history, and to put an end to the fanatics’ destruction of Islamic antiquities since 1933, the last episode of which was their demand to convert Khadīja’s house in Mecca into a public toilet.[2] These antiquities are part of the memory of humanity and provide invaluable services to science and history. Neglecting them, or rather eradicating them, constitutes a crime against this memory, a crime against science and against the history of Islam. Archaeological excavations have yet to make a valuable contribution towards sifting through all the oral narratives that confuse the truth with half-truths or even the opposite of the truth, and defy researchers to distinguish between them.

[1] Sunan an-Nasā’ī 1578.

[2] The removal of the final traces of Khadīja’s house was highly controversial, with opponents accusing the Saudi’ state’s adherence to Wahhabism as the cause, in that the doctrine eschews all forms of worship that focus on places other than the Kaʽba as potentially fostering a form of idol-worship. By 1950, the house had been levelled by the Saudi government along with other significant historical sites. (Ed.)

Main image: Ruins of an ancient church dating from the 4th century, possibly Nabataean, and said to be the oldest standing church in the world. Discovered at Jubail in Saudi Arabia in 1986 and awaiting examination.

Read Part 1 of this essay here