Almost every religion is inhabited by fanaticism, which is the lawful offspring of a religious narcissism promulgated via slogans of greatness. People like us are ‘God’s chosen people’ and we are ‘the best nation brought out to people’[1] and we are the ‘saved sect’. In the 1990s, I became aware of the existence of a Christian group of about 120 people spread out over six countries, who called themselves the ‘Kingdom of Light’ and called the rest of the world's population the ‘Kingdom of Darkness’, soon to meet the fate of Sodom, the city of Lot since the end of the world was nigh. Incidentally, apocalypse delirium is a symptom of clinical schizophrenia.

RELIGIONS THAT HAVE been redefined in the light of comparative religion sciences have largely tamed the tendency towards religious narcissism and intolerance. Redefining Islam with these sciences may yield similar results for us too. [2]

Today, political Islam and the quasi-modern ruling élites are competing for the legitimacy of Islamic collective memory. The competition is in fact being settled in favour of the Islamic far right. This is because the Salafist collective memory, whose motto is “Do not believe anything other than what God and the Messenger said” (in other words, fight against reason and science with all of your might) is being filled by the school of religious absurdity with a religious discourse that grinds love down at the mill of political Islam, which today constitutes the far right of Islam.

Instead of waging this miserable competition over who has ultimate control of an outdated collective memory, ruling élites have adopted a programme to re-shape this collective memory by inculcating it via the study of comparative religion in the a school of religious rationality. The French Third Republic was able to overcome sectarian conflicts between Catholics and Protestants through inculcating a pre-Christian history capable of creating a collective identity, one stronger than the religious identity of both Catholic and Protestant and with which all French people could identify.

Arab and Islamic countries could benefit from this experience and form a common collective identity stronger than the current sectarian identities

Arab and Islamic countries could benefit from this experience and form a common collective identity stronger than the current sectarian identities. It can do this by providing historical instruction in all eras of our history instead of confining it to its last moment, that is the Islamic moment, making it an ‘A to Z’ history. Egypt, for example, could study the Pharaonic period and the Coptic period, and so on, right up to the Islamic period. In Tunisia, history begin with the foundational era of Carthage, through to the important Roman period that influenced both Tunisian and Maghrebī Islam. For Mālikī jurisprudents took over a number of provisions from Roman law, which later became customary. Finally, we have the Islamic moment, the most influential and lasting of all of these three moments. The Tunisia case is inspirational in this respect, and reformist elites in the land of Islam might do well to draw inspiration from its long and rich experience of reform.

The disciplines of the phenomenology of religions that are to be taught include the comparative history of religions, religious sociology, religious anthropology, the psychology of religions, linguistics, philology and hermeneutics (a science of interpretation). To this I would add another science not originally part of religious phenomenology, but now is one of them: neuroscience. I also add philosophy, which although not a science as such, provides the critical thought necessary for a historical-critical approach to the phenomenon of religious faith and for immunizing the minds of new generations against the virus of religious delirium.

For Islam is not only a religion, but also a political-military project founded upon jihād until the Day of Judgment with the aim of achieving two goals: bringing humanity into Islam and killing the last Jew, as a sound hadith narrated by al-Bukhārī says and which Hamas included in Article 7 of its Charter drawn up in 1988.[3] Reform here requires the teaching and studying of the faith through the science of comparative religion, so as to de-sanctify its political and military ingredients and enable their separation from religion, the only sacred ingredient in this. Anything else and reform will remain a mere cosmetic exercise.

As to the objection that teaching religion through religious phenomenology would remove its sacredness, in that its Texts would be considered no different from any other literary texts, the fact is that not teaching Islam in the same way that other religions in the world are taught means that we leave people to be blind in their ignorance, merely so that they ‘remain religious’. According to this logic, it is better to be obscurantist, that is, to have a nation of ignorant religious people instead of a nation of educated people, scholars, and citizens who are indifferent to religious rituals. If any religion fears knowledge, then we should consider knowledge to be superior to it.

Not teaching Islam in the same way that other religions in the world are taught means that we leave people to be blind in their ignorance

Better than indulging in this everlasting debate, let us look at reality. Studying religion within the discipline of religious phenomenology and teaching this discipline in schools and universities is something that began in Europe centuries ago. And what was the result? A majority of the believers are mild and tolerant of the other and of the other religion, 25 percent are indifferent, but of these only 6 percent are convinced atheists. As for the Islamic Republic of Iran, where everything is religious – in the mosque, school, university, media, street and home since the revolution – what was the result? Thirty years of religious delirium has produced a population of 30 percent atheists.[4] Why? Because too much religion actually kills religion. Or, as the wise proverb says, ‘everything that goes beyond the limits turns into its opposite’.

Without this scientific approach, we will never move beyond the eulogistic approach to the critical approach, nor from takfīr[5] to thinking and taking a new look at the problems that religion and life pose for us. The fear of losing faith is in itself symptomatic of a fearful, suppressed doubt concerning the truth of their faith. The courageous and intelligent educational decision is one that is based not on unreasonable fears but on the well-defined public interest that makes religious reform a rational imperative.

As for the argument that the sciences of religious phenomenology are the product of a western, Judaeo-Christian environment and cannot be applied to the Islamic Texts without doing a violence to either, I maintain that it is totally possible to apply these sciences since, like all sciences, they were produced by the universal human mind, and its results are recognized by all those with sound minds. Just as the natural sciences are valid for every place, so are the sciences of religious phenomenology with which Hindus now study Hinduism and Buddhists study Buddhism. How can Islam not be studied or taught in these when it is descended from a deep cultural cross-pollination with the Jewish and Christian religions? The Qur’ān itself tells us that:

“Most surely this is in the earlier scriptures, the scriptures of Abraham and Moses.” [6]

Most of the stories of the prophets in the Qur’ān are taken from the Old Testament. Sūrat Yūsuf, for example, is a focused summarisation of the story of Joseph in the Old Testament. Likewise, in the Holy Qur’ān – under the names Zabur and Zabūr – we find verses quoted from the Song of Songs.

I particularly insist on the need to teach the comparative history of religions, from middle school to higher education of course, with curricula prepared by specialists that are appropriate for each stage of education. The comparative history of religions is based on a fundamental axiom: that it is not possible to understand the beliefs, rituals, symbols and myths of living religions such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam except by comparing them with the beliefs, rituals, symbols and myths of the earlier religions from which they developed, especially the Babylonian and Egyptian religions. Setting the phenomenon of the religion in history, the comparative history of religions makes it understandable historically and intellectually, that is, without the aid of secrets or mysteries which render the human mind incapable of questioning and understanding. There is nothing like the comparative history of religions and religious phenomenology for liberating the believers from the psychological slavery of the ancestral heritage that has turned many of our jurists into moving ‘heritage’ mummies.

The fear of losing faith is in itself symptomatic of a fearful, suppressed doubt concerning the truth of their faith

Can the human mind grasp all the secrets of faith via religious phenomenology? Maybe not. But the question is why? In both cases, the individual must be given the right to ask, while at the moment asking is forbidden in traditional Islam. So far, the sciences of religious phenomenology have been able to decipher most of the symbols and myths of the Old Testament. Archeological discoveries continue to provide more decipherment, as has been achieved in Israel, Palestine and Sinai over the past forty years.

By enabling the human mind to understand the religious phenomenon rationally it makes this phenomenon a relative phenomenon. Because everything that is historical and relative evolves and adapts to the requirements of life in every era and every land. The discovery of America was the real starting point for religious reform in Europe, because the presence of religious beliefs and rituals among its indigenous people – had had not been reached by the call either of Judaism or Christianity, issued a salutary shock to the Christian consciousness. It discovered what phenomenology terms ‘the unity of the religious experience’, one that is manifested in belief in the existence of the world of the unseen, a world that is transcendent, sacred and inhabited by spirits and gods, irrespective of the different historical manifestations of what is an essential unity in the religious phenomenon.

Suggested Reading

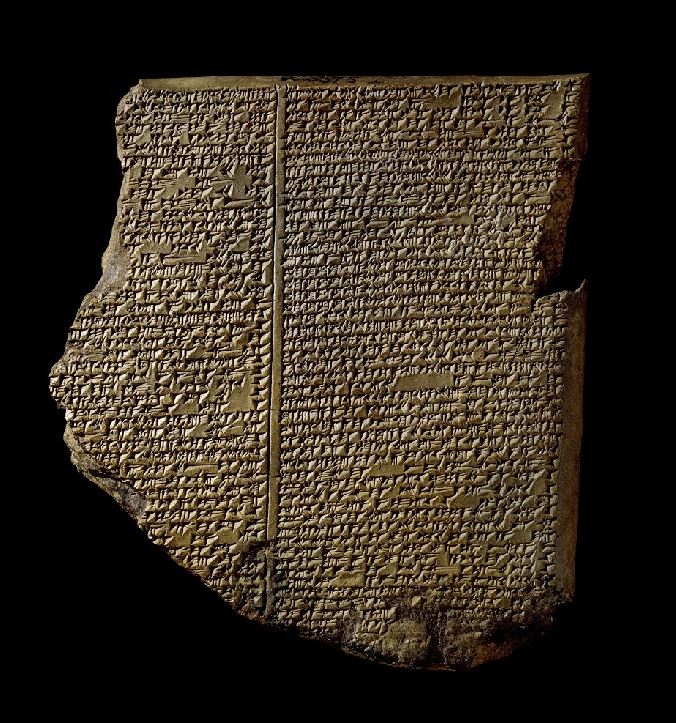

When the school pupil or student learns that religious symbols are the same in both the pagan and monotheistic religions, and that they have come down to us from the two pagan religions – Babylonian and Egyptian – to Judaism, he learns religious tolerance and the necessity of interfaith dialogue, and it cultivates within him a curiosity for knowledge and a love of research. The Babylonian myths were transmitted by the Jewish presence in Babylon during the Babylonian captivity in the sixth century BC, and their translation of the Babylonian myths on the origin of the universe which was created by seven gods, in seven days – into the Book of Genesis. Hence the myth of the sanctity of the number seven: in the Babylonian religion, for example, we have seven gods, seven heavens, and seven lands. In addition, the myth of ‘the first couple, Adam and Eve’ was translated by the Prophet Ezekiel in the Book of Genesis from Sumerian myths, which called Adam Adapa, meaning the man created from clay. The Hebrew Adam means “the earth’s skin” as it does also in Arabic. There is also the myth in the Book of Genesis of Noah’s flood which was taken from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which says, for example:

“O Utnapishtim [translated as Noah], build an ark and carry in it two of all life”

in order to continue the reproduction of the living after the flood. Similarly, the city of Lot is originally a Babylonian legend. Judaism adopted many of the myths of the Egyptian religion, and from there it transferred them to Christianity and Islam.

[1] Qur’ān, III (Āl ‘Imrān) 110.

[2] This essay is reproduced from an interview with Nāṣir ben Rajab and Laḥsan Warrīgh in January 2013.

[3] The hadith in question is Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2922 (et al.): “The last hour would not come unless the Muslims will fight against the Jews and the Muslims would kill them until the Jews would hide themselves behind a stone or a tree and a stone or a tree would say: Muslim, or the servant of Allah, there is a Jew behind me; come and kill him; but the tree Gharqad would not say, for it is the tree of the Jews.” (Ed.)

[4] The author was speaking in 2013. Today the figure is even higher, according to an analysis by the Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in IRAN (Gamaan) entitled Iranians’ Attitudes Toward Religion – A 2020 Survey Report which found that that only 32% of the population identified as Shi’ite Muslim and that ‘half of the population reported losing their religion’ (Ed.) Upload the report to Almuslih

[5] See Glossary.

[6] Qur’ān, LXXXVII (al-Aʽlā), 18.

Main image: Fragment of a clay tablet from the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (Tablet XI), with an Assyrian account of the Flood from the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic.

Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh