As things stand today you will find that the average Muslim knows nothing at all about the religion of his Christian fellow-citizen, while the Christian knows every detail of the religion of his Muslim fellow, since he studies it at school in Arabic language texts and in history and in the media. But in all these agencies in the country you will not see anybody addressing anyone other than Muslims.

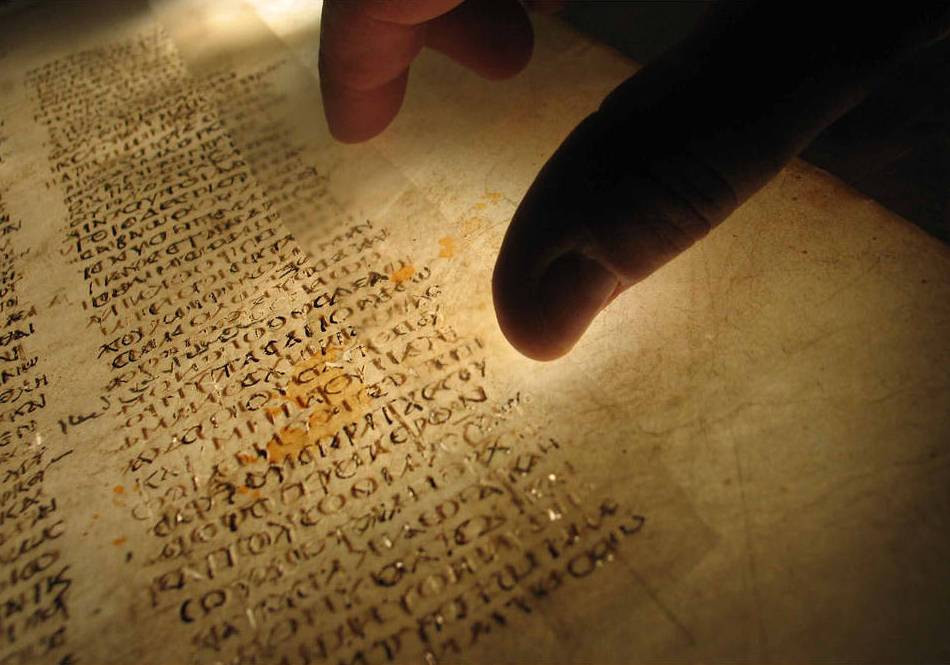

THE MUSLIM ONLY KNOWS about the religion of his Christian fellow in Egypt according to what the Islamic faith in its texts, commentaries and fiqh says about it. This contrasts with, and indeed contradicts, the Christianity that the Christians themselves are familiar with from their four Gospels and their 23 Apostolic letters. Islam’s view on the revealed Gospel depends on those it calls the adherents of the Gospel of the Hebrews. Yet these were communities in schism with mainstream Christianity and whom Christian Ecumenical Councils consider to be errant, heretical groups. These councils only recognized the four Gospels now in general circulation. Just like the Prophetic Hadīth, they were not revealed but were written down by its authors from accounts of the Messiah and events of his time.

From this ecumenical decision the adherents of other Gospels were suppressed, anathematized and erased. The adherents of the Gospel of the Hebrews hailed from several sects, some of them Nestorians, some Bardaisanites[1], some of them Arians, and so on. With the consolidation at the councils of an agreed-upon Christianity as the official religion of the Byzantine Empire at the time of Constantine, the suppression took on an organized form. This forced them to flee far from the reach of imperial religious might, right into the wastes and wildernesses of the Arabian Desert – along with their Gospel of the Hebrews which is what the Qur’ān took to be Christianity.

They raise themselves aloft to a station above that of God

With this historical understanding we find that the target of the Qur’ānic verses expressing hostility to the People of the Book are the particular People of the Book who were living in the Arabian Peninsula during this period. With the passing of time and the clearing of the Peninsula of all but the Muslims and Islam, the adherents of the Gospel of the Hebrews waned so that they became obscure and disappeared from history. All, that is, except some scattered remnants in northern Iraq and Syria, who lost their connection with their original beliefs so that the remnants went their separate ways. This means that the rulings of the Qur’ānic verses concerning them became obsolete with the severance of the cause (which governs its existence or non-existence) from its effect, as the Muslim fundamentalists see it. Some of our fellows, however, suffer from an imbalance in the majesty of faith and its innate tolerance with its spectrum of colours embracing all complexions. Instead they raise themselves aloft to a station above that of God, and hold their decisions to be above God, so that they destroy and burn houses in which the name of God is invoked. It all brings to mind the people of the mosques of mischief.

From this historical projection through the window of faith we can understand how Qur’ānic verses on freedom of belief can juxtapose with verses of incitement and hatred against the People of the Book. This can only be because they refer to events specific to a time and a place. For the verses affirm to us a Gospel wherein is guidance and a light and a Torah wherein is guidance and a light. They also ask How come they unto thee for judgment when they have the Torah, wherein Allah hath delivered judgment?[2] It would not be true to say that we are committing the very sin of selectivity we wish others to refrain from, and are selecting verses that were subsequently abrogated. This is patently not a selection of verses of peace and tolerance assumed to have been abrogated by verses of hatred and war. Rather, it is those who harbour deep-seated intolerance who imagine that the Islamic faith has incorporated and abrogated all previous religions, or that the Qur’ān has incorporated and abrogated all previously revealed holy books.

Here faith can assist us, for faith assumes that God’s majesty cannot permit some people to distort some of His words (the Gospel and the Torah) while preserving other words of His (the Qur’ān). For His words all issue from Himself and His holy utterance. Hence a sound faith must assume that all His words are the object of His protection and preservation. Even if we were to go along with them and maintain Islam’s abrogation of all religions and books that preceded it, we have in the Qur’ān a lesson and a precedent to follow. What is amazing about this lesson is just how clear it is. For you will find that the overwhelming majority of verses that have been abrogated remain preserved in the Qur’ān. They thus complete, clarify and explain the course of the Qur’ān’s development as a result of its interaction with the real world, where it gives and takes, abrogates and replaces verses, bringing some to the fore and consigning others to oblivion – in a continuous debate and discussion with changing events in the world. The lesson here is that God has seen fit to preserve His earlier books and has not abrogated them. He has preserved the believers in these religions as a visible indication of His divine will, just as He has preserved the abrogated verses though His desire and His will.

Some have yet to rise above the stage of Islam to the stage of faith

We are obliged to come to the clear conclusion here that the existence of other religions and believers is God’s will. Yet despite this some of us today seek to override this will. It was God who wished that the inhabitants of our planet should be many different peoples, tribes and nations, so that they should get to know each other. The Qur’ān confirms that that was the purpose of our being created, and that God wishes that this difference should remain in existence. But this difference is a difference of acquaintance and familiarity, a difference that completes the other. In this way God has averred the need for the existence of difference through His will and through His being the sole creator. It is a declaration that the riches of human life and the open arena of faith is capable of embracing all differences. God simply made it clear that if He had so willed that all people on the earth be one community, He would have made it so. Yet some of us choose to challenge this divine will and seek to place their own desires above that of God, or their own will above that of God. This is because their faith is defective, and their conscience has failed and collapsed.

Suggested Reading

Perhaps the most important element afforded by the Qur’ān to this open faith of Islam comes from the story of Noah’s Flood, a tale familiar to all believers in the Abrahamic faiths. It states that Noah was displeased by the errant nature of humankind and called for its collective destruction. Since God had decided at the beginning of creation that the call of a Prophet should be answered, He decided to give Noah an answer. But the lesson He gave the faithful was that it is impossible to remove all difference. For from the very progeny of the believers saved from the Flood there derive all those who disbelieve and differ, all those who have seceded, committed acts of rebellion and persist now in the form of disparate religions. This is a confirmation of the will of God, which is above the will of men, even if they be of the stature of messengers and prophets like Noah. You can see how much God magnified the stature of faith and placed it on a level higher than Islam. And to some of us God directs the following Hadīth:

Say we have become Muslim, but do not say that we have believed.

He has done this since some of these people have yet to rise above the stage of Islam to the stage of faith.

[1] From the Syrian philosopher Bardaişān ( ܒܪ ܕܝܨܢ ) whose belief system incorporated some astrological and occult beliefs into Christianity. He held unorthodox views on the Trinity. He apparently denied the Resurrection of the Body, but held that Christ’s body was endowed with incorruptibility as with a special gift. He is thought to have held Gnostic views which subsequently influenced Manichaeism. Some of his followers were Docetists. Bardaişān lived from 154-222 AD. (Ed.)

[2] [Qur’ān: V,43,44, 46].

Read Part 1 of this essay here