Anyone who attempts to heal the rift between the nation’s brothers usually makes a great effort to find a legitimate document supporting his position, and finds a rare few, such as, for example, the Qur’ān’s description of the Christians as including priests and monks who are free of arrogance, and that they are to be treated kindly since they are the people with the greatest affection for Muslims, as opposed to the Jews who are held to be the most inimical.

THIS IS IN ADDITION to a number of rare Hadīths such as ‘the finest soldiers are from Egypt” and the demonstrating of good will to the Copts of Egypt is a fine thing. Yet all these unique Hadīth were rejected the moment the door was opened to those who saw themselves as having been granted custodianship of the Law, who based themselves on the Verse of the Sword[1] which abrogated the verses of freedom of religion, and the Hadīth of the Prophet that derived from it.

It is safer to be honest with oneself. It is a nobler thing than selecting a text and concealing another one that contradicts it in order to support a particular position or a point of dispute. Honesty means respecting scriptural Texts that might say the opposite, definitely and irrefutably, respecting documented evidence and meanings shorn of any overlay of hostility against the People of the Book. It also means our respecting ourselves and refusing to flee from facts that constitute an integral part of our faith and which we therefore have to accept and cherish in their entirely or refuse in their entirety. For anyone being selective in this regard shows up his attempt to flee from a position that leaves him with a feeling of inferiority or of shame (or both), at a time when modern human rights have become established as noble and exalted principles.

Selectivity is a type of opportunism perpetrated upon the sacred Text

Selectivity is a type of opportunism perpetrated upon the sacred Text, and indicates a lack of respect for it let alone (and this is much more important) a crack in the soul in one’s belief with its ensuing damage to the conscience.

This current reading relies on faith, which is absolute and unlimited. This is a meaning of faith which does not have a physical structure, it is not associated with the minarets that the Swiss failed to erect nor is it troubled by the bell tower of a church built in any neighbourhood. For one cannot weigh or know the quantity or standard of this faith. But if we resort instead to reading what the meaning of faith is, it will preserve us from over-excessive recourse to the letter of the sacred Texts, and keep us away from passing through those grand corridors that furnish nothing of any certainty to those who enter into dispute on these Texts – as to whether they constitute ‘sound’ or ‘ambiguous’ Hadīth, or how reliable their chain of transmission turns out to be, or how ‘weak’ or ‘strong’ that chain is. Understanding the meaning of faith brings us into a world of concepts and perceptions of true value, to lofty values that hail from within mankind, values which mankind has inherited genetically from its primitive forefathers who worshipped the deity of the earth. What offends most against the law of this deity of the earth is that there should fall upon its soil a single drop of human blood, for the shedding of human blood constitutes a universal crime that cannot be atoned for.

So there is a vast interior arena called ‘faith’ which resides within the human soul alongside passions appropriate to its inclination towards the Good, and its resistance towards inclinations towards evil. This is irrespective of who the believer is, or what his religion is.

The recourse to religion as a space for a necessary psychological comfort therefore grounds itself upon faith in a beautiful, just divinity, who is all Good. All of these conceptions are non-material and founded instead upon feelings. These feelings are the cornerstone for the acceptance of religion – in the first place as a faith, and in the second place as a body of religious Texts.

If we work with this basic cornerstone – faith – we shall find more than one gateway, characterised first and foremost by honesty with oneself, an honesty which affords faith its contentment and reassurance. It relies upon the juxtaposition within the soul between this faith and the concerns of one’s conscience, which depends upon precise standards to distinguish the meaning of peace and the meaning of justice, sincerity, mercy and humanity. It is a collection of requirements which it demands for itself as well as for others, and since it is basically the establisher of these values, faith in its turn has need of these values to feel secure and reassured. So faith broadens them into absolute principles for everyone, in order to gain reassurance that other believers – even those of other faiths – will not transgress upon their personal space and invade their peace and security. This is because they too constitute ‘believers’.

Churches are sanctified edifices according to the Islamic faith

This gateway is a frame which establishes the validity of the Text and its certainty, and at the same time our lack of need to adhere to some of the rulings of the Text when circumstances of time and place change, or when these rulings are no longer suited to the latest developments. It is also part of the essence of faith and is founded upon it. Were it not for this it would no longer be a faith. Since the end of faith is an absolute, unique deity, the honouring of God and all places where His name is invoked constitutes the cement that groups together all religions under the one umbrella termed ‘faith’. We will see convincingly that in the Islamic religion, as in the other religions, the first priority for the believer’s soul is to educate his conscience to sanctify and honour any place where the name of God is invoked. By simple intuitive logic the corollary of this is that churches – which are houses wherein the name of God is invoked – enter into the category, and are on the map, of sanctified edifices according to the Islamic faith.

It may be that we receive an uncompromising response to this, saying that the Christians are no longer believers since they hold that God is one of three persons, and have falsified the Gospel revealed by heaven to their Prophet ‘Īsā[2] and that they consider ‘Īsā to be a god, while he is a man. Therefore their house of worship is a place wherein idols are invoked, and deserves to be destroyed and burnt down. Moreover, there are images, statues and ikons in that house, things which the Islamic Texts consider to be a form of polytheism and paganism. So now we shall endeavour to resort to the meaning of ‘faith’ and of the sanctification of any house where in the name of God is invoked – and we will do this by adopting as guide the Qur’ān itself and the history of religion.

Suggested Reading

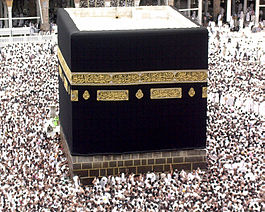

Islam – a religion which is against all forms of polytheism and proclaims the uniqueness of one eternal being – delivered a strong lesson in this regard in the protection it afforded the Meccan Ka‘ba from a crushing aerial attack undertaken by an army of Christians at the incident known as ‘The Year of the Elephant’[3]. God brought this about in order to protect a house sanctified by something in the region of 300 worshipped idols and where sacrifices were made to one other than God. The clear lesson here is that despite the fact that the Meccan Ka‘ba was at the time one of the most egregious citadels of paganism in the world, the One God that tolerates no intercessors on His behalf nor partners in godhead and rejects the arts of sculpture and depiction on the grounds that nothing is like unto Him, resolved to protect this place with all its overt, barefaced heathenism. This act of protection was a unique event in the history of religions and rests upon the conception of what faith is. The tribe of Quraysh[4] considered these idols to be intercessors to a single Lord and that they were representation of pious, pure folk sanctified after their deaths. The Qur’ān supports this belief when it says:

And if thou wert to ask them: Who created the heavens and the earth, and constrained the sun and the moon (to their appointed work)? they would say: Allah. How then are they turned away?[5]

Here God resolved to apply the meaning of justice (one of the pillars of faith) and refused to support His beloved Christians, those believers of the latest of the true, celestial religions up to that time. Instead He punished them by pelting them with stones of clay since they had resolved upon transgressing upon a house in which the name of God was invoked. This indicates His prohibition against the destruction or burning of churches by activists acting against the so-called ‘abomination’ in which God’s name is invoked, activists who therefore similarly deserve the punishment of God’s birds. As a corroboration of this is the fact that no matter how much you search, you will not find in the Qur’ān any indication to destroy or burn houses in which God’s name is invoked – no synagogue, no church, no Buddhist nor Confucian temple. On the contrary, God unambiguously declared that Muslims are to destroy and burn mosques of mischief[6]. And this is what the Prophet put into practice when he burned down one of the mosques in Medina over the heads of those inside, since it harboured seditious plots against other people with an aim to destroy the community. If God never once ordered the destruction and burning of churches, He did nevertheless order the destruction and burning of mosques – the mosques of mischief.

[1] [Qur’ān: IX,5]: Then, when the sacred months have passed, slay the idolaters wherever ye find them, and take them (captive), and besiege them, and prepare for them each ambush. But if they repent and establish worship and pay the poor-due, then leave their way free. Lo! Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.

[2] ‘Īsā ( عيسى ) is the term given in the Islamic faith for Jesus. Jews and Christians recognize in the Greek form of the name Ιησους (Jēsūs) – or in the oblique case Ιησου (Jēsū) – the Hebrew name יהושוע (Y’hōshū‘) in its later Hebrew and Aramaic equivalent ישוע (Yēshū‘). The Hebrew name parses grammatically and has a meaning: ‘God is Salvation.’ There is no recognised grammatical parsing for the Arabic name. (Ed.)

[3] The ‘Year of the Elephant’ refers to an event said to have occurred at Mecca about the year 568-569 AD in which Abraha, the Christian ruler of Yemen, marched upon the Ka‘ba with a large army, which included one or more elephants, intending to demolish it. However, as he prepared to enter the city, a dark cloud of small birds appeared carrying small rocks in their beaks, and these bombarded Abraha’s forces who fled in panic. The event was recorded in the Sūrat al-Fīl (‘Elephant Chapter’) of the Qur’ān: Hast thou not seen how thy Lord dealt with the owners of the Elephant? Did He not bring their stratagem to naught, And send against them swarms of flying creatures, Which pelted them with stones of baked clay? [Qur’ān: CV,1-4]. (Ed.)

[4] The tribe that had tutelage of the Meccan Ka‘ba.

[5] [Qur’ān XXIX,61].

[6] [Qur’ān IX,107-8]: And as for those who chose a place of worship for mischief and disbelief and in order to cause dissent among the believers, and as an outpost for those who warred against Allah and His messenger aforetime, they will surely swear: We purposed naught save good. Allah beareth witness that they verily are liars. Never stand (to pray) there.

Main image: Burning “houses wherein the name of God is invoked” – the May 2011 clashes in Cairo that left two churches in flames.