It is well known that the religious heritage circulating in the collective mind and in the cultural and social environment of the Islamic world still generally retains the power to exercise authority and control, and still retains the authority to 'enjoin that which is good and forbid that which is evil'. Moreover, this same tradition has never ceased to define the Muslim individual's identity as a legal entity. It intervenes in the formation of his culture, his convictions, his behaviour, his ethics and his attitudes and even his foreign relations; it defines the nature of his relationship with others and with the physical world around him. What is also clear is that the religious heritage, in the alphabet of Islamic religious thought with all its cultural, denominational and folkloric elements, is an accumulative legacy that intersects with itself and is passed on in the genes.

BY MAHMUD KARAM

THIS MEANS that all the religious mental accretions that attach to this same tradition or weave themselves into it, or which intersect and merge with it at various stages in the form of cultural activity, written texts or folkloric practices – are customarily taken to constitute the ‘religious heritage.’ It then takes on the characteristics of sanctity, sovereignty and control, on the grounds that it is founded upon a ‘previous religious tradition’. Being formed from this heritage, it adopts all of its uncontested, absolute, metaphysical fundamentals as its point of departure.

Religious heritage is an accumulative legacy passed on in the genes

This being the case, the accumulative religious heritage becomes a constant focus of study as to its legitimacy in contemporary governance, through its all-embracing, textually related connection with the historical, sacralised, unquestioned assumptions concerning the religious tradition, from which are derived all the entire historical legacy of religious writings.

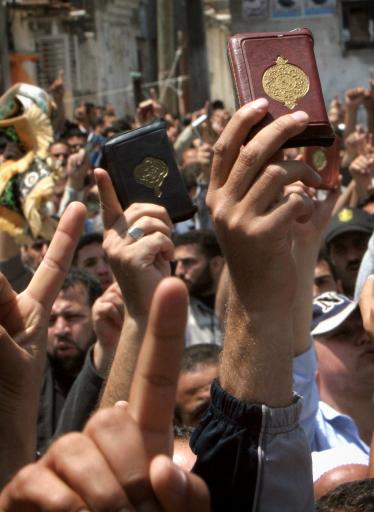

Moreover, it becomes so rooted in the Islamic intellectual mindset that it turns into a thoroughgoing certitude that cannot accept of any doubt, criticism or alteration. The religious text [man holding up a Qur’ān in a crowd?] – whatever the nature of this ‘religious’ text is – is no longer the product of its historical, geographical, or chronological environment and thereby subject to the influence of all its historical factors. That is why the Muslim continually believes that the religious text – which in the end merely reflects this religious heritage – must be held to remain outside the context of history and bear no relationship at all to the vicissitudes of circumstance, to changing times or the varying climates of scientific and social development.

Hermetically bound to the past

From this starting point the successive accumulation of knowledge and religious custom – which, as we mentioned, takes on the stamp, conception and sanctity of the religious heritage itself – must remain structurally, organically, conceptually and historically connected to its earlier traditional, textual heritage, and remain an extension of it. It must therefore take on the aspect of certitude, of something outside time, of absolute sovereignty.

As a result of the Islamic mindset’s total and absolute belief in the non-chronologically delimited sovereignty and certitude of the religious tradition, the accumulated legacy inevitably turns into a bloated religious apparatus wielding absolute powers of control, direction, domination and sovereignty.

The legacy turns into a bloated religious apparatus wielding absolute power

Whereas it should rather be very much incumbent on Muslims to deal practically, logically and intellectually with their religious heritage as something that is merely a matter of human theories which are independently arrived at and capable of being either correct or incorrect, and which subject to change or substitution, to criticism and analysis, or to a process of filtering and acclimatisation. Most importantly, the tradition ought to be subjected to epistemological study as raw material solely for the religious sciences, and not transformed into a conveyance towards any type of intellectual culture saturated with the mentality of command and control.

By subjecting it like this, the religious heritage will be prevented from turning turn into a religious apparatus and taking on the aspect of something sacred, certain and outside of time. Yet all the evidence of events past and present indicate that the religious tradition – with all its textual authority, cultural baggage, historical literature, contrived interpretations, tendentious religious concepts and legal sciences, with all its successive accumulations of past and present knowledge – has indeed become a bloated cultural and religious apparatus exercising dominance. It is infested with narcissistic deliriums of superiority, and is saturated with an unshakeable belief in its own infallibility, in its transcendence and its sanctity. It suffers from mythical imaginations and fantasies, and rules by means of a narrow dogmatic, monopolising ideology.

The danger is therefore always present that the religious heritage will become transformed into a highly influential religious apparatus enjoying absolute powers and exercising sovereignty and control. For it is attempting with all its powers of language, its jurisprudential armoury, its legal precedents and inherited texts to set about creating popular spaces brimming with the ideology of extremism, militancy and hatred, whose basic aim is to mobilise hearts and minds against anyone who differs from them, whoever they may be.

It is infested with narcissistic deliriums of superiority

This religious, populist mobilisation relies on the extremism and militancy channelled by religious associations via their pulpits and media propaganda and their various sloganistic publications. Their religious identity is founded upon this inherited religious discourse, since a religious identity is fixated upon a closely bound legacy that takes no interest in social or cultural factors, or of changes in environment or development. It is therefore inseparable from its hoary religious tradition, and its behaviour is directly determined by its ancient discourses that have been fashioned in cultural molds designed to repudiate the other and reject and repress difference.

Absolute purity, absolute intolerance

There is another factor that is closely related to the religious heritage, which supports it and is in turn supported by it, one which takes it as its point of departure and at the same time perpetuates it. This is the fact that the inherited religious mindset of the Muslims is generally characterised by ‘absolute purity,’ something that is beyond reproach and devoid of any weaknesses or gaps, immune from breaches or pitfalls. This conviction has grown over the course of time and as the religious legacy, powered by a theatrical religious mania, accumulated to the point where the religious heritage in all its many and varied interpretations and applications fed upon the ‘illusion of purity’, as the thinker ‘Alī Harb put it. As a direct result of this conviction there emerged the concept of superiority over all other religious traditions, bringing along with this a tendency to sanctify the Muslim absolutely and belittle all others, or even express contempt for their beliefs and cultural achievements.

The belief in the purity of the religious tradition, and the absence of any intellectual shortcomings to it, spawned in the Islamic religious identity a virulent spirit of intolerance. This is not surprising since the religious thinker continues to uphold his religious identity in a manner inculcated by a packaged, oral repetitive religious education that rehearses many of the superficial and trite opinions given out by religious preachers and pulpit sermonizers. He regurgitates the literature of the religious tradition as if they contained absolute truths and at the same time clings to his opinion on this as if they were final, conclusive solutions to the problems of mankind.

It is attempting to set about creating spaces brimming with the ideology of extremism

There is another kind of religious intellectual who never ceases to cite the views of western philosophers, thinkers and inventors and tries as much as he can to refute their ideas concerning his religious tradition or make out in one way or another that they actually embody it. To do this he twists their views so that they comply with his religious orientations, thus establishing in a silly, comical manner, that his religious tradition somehow pre-dates by hundreds of years the views of these philosophers, thinkers and pioneers concerning the natural world, the origins of life and of Man.

A third type of religious intellectual is the one who depicts western culture, appropriately or not, in terms of corruption, decay and moral disintegration, and indeed predicts its imminent collapse and even wishes for this to happen. One fails to understand why he should wish that this culture should collapse and come to an end given that it provides him with every means of comfort, communication and high-standard medical treatment and education.

A culture of fear

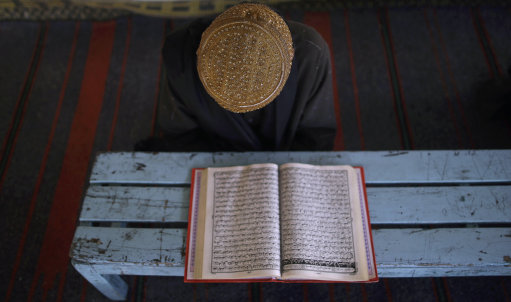

Given all of the aforementioned, we are left having to ask ourselves the logical question: What is it that induces the Muslim generally to utterly submit himself without reflection, study, analysis or criticism to the religious tradition – whether this be in the form of what he is accustomed to receive by word of mouth or what he inherits culturally and traditionally from his forebears, or what he learns by rote from educational syllabuses and religious institutions [Azhar photo?], or under the influence of society and environment, or from what is commanded him from religious authorities, or more often than not from what is deeply entrenched in his mentality?

Many are reluctant to challenge the religious tradition for fear of their own lives or their social standing

I think the answer boils down to a key point that focuses on the prevalence of a culture of fear, something that has been deeply rooted for a long time in the mindset of the Islamic personality. This is a fear of being set free from the domination and control of the religious tradition.

I can identify three fears that have formed, and still form, a major impediment to most Muslims, preventing them from stepping out beyond the overwhelming control and authority of the religious tradition and freeing themselves of its absolute, uncontested certainties.

The first aspect of this fear one finds represented in the individual’s constant terror of rejection –rejection by his Muslim doctrinal and social environment and its collective religious culture. This religious rejection of the individual, who refuses to submit to the practices of the religious tradition, takes many and varied forms: defamation of his person, attacks calling into question his ethics and his sense of honour and calling for him to be isolated socially, in addition to media fests adopted by the religious current to circulate denigrations of all those who refuse to see themselves obligated to bow down to the authority of the religious heritage. At times this religious repudiation can get the point of death threats and physical extermination.

Suggested Reading

Consequently many are reluctant to challenge the religious tradition for fear of their own lives or their social standing as a result of a savage religious and social rejection. It accounts for why some give up practising their human right to criticise or boycott that which they find unsuitable, and prefer to acquiesce to the prevailing cultural tradition and go along with its behaviour and culture, with its forms, sentiments and customs, since he sees his personal safety and the maintenance of his social standing depends on so doing. Mankind in general fears social rejection and is nervous about opposing the prevailing established trend, for fear of one day finding himself outside the circle of social and religious acceptance.

Fear of loss of identity

The second aspect of this fear is the terror the Muslim individual feels for the loss and obliteration of his religious identity should he even think of stepping beyond the bounds of his religious tradition. This is because, as a believer, he feels that the religious tradition reflects his very being and personal identity, without which he would feel lost. For he only has one heritage to defend, dig in and barricade himself behind; it represents all of his past, present and future, and constitutes the first and last line of defence in maintaining contact with his distant past.

He only has one heritage to defend, dig in and barricade himself behind

When he finds this identity faced with criticism, analysis or deconstruction he quite naturally feels that it is in danger – for what can a Muslim take pride in, or glory in, other than his religious identity which he holds to be holier, superior and purer than any other religious identity? It is, in the end, his point of reference for all aspects of his life and constitutes the framework defining his relationship with others and with the world. Consequently the individual who possesses nothing else than his religious tradition for his entire identity, who stakes at the same time all of his present and his future on this tradition, naturally cannot accept any prejudice to this. He thus consequently fears the loss of his religious identity since this will automatically mean the loss of himself, his dismemberment and his ultimate collapse.

Fear of punishment

The third aspect of this fear is the Muslim individual’s terror of punishment in the Afterlife should he attempt to step outside of his religious tradition. For there is a powerful religious belief untouched by any form of doubt that any opposition or criticism he makes to the religious tradition equates to violating the commands of the Creator Himself and will thus expose him to punishment and torment in the Hereafter. This is despite the fact that the Creator stipulated that he should employ his intellect for the purpose of thinking, reflecting, studying and gaining insight.

In conclusion, perhaps the only way to free oneself from the tyranny and control of the religious heritage lies in the ability of the Muslim individual to overcome his fears, liberate himself and pass beyond them. If not, the results of his sacralisation of, and complete conformity and absolute subservience to, the religious heritage will be fatal for him, since it will grant full license and control to his religious legacy to dominate his mind, his thinking, the decisions and the choices which he makes, and ultimately his entire life.