The extremist element in contemporary religious discourse manifests itself in three conspicuous aspects: the male dominance attitude which excludes women; the denunciation of treachery attitude that calls into question the doctrinal propriety of others and their intentions; and the conspiratorial accusatory attitude which sees the ‘West’ as an implacable enemy from which nothing good can be expected and which is primarily responsible for the appalling conditions, the backwardness, the calamities and failures in growth, production and education that the Muslims are suffering.

WE HAVE EARLIER demonstrated the inability of the prevailing religious discourse to achieve its four principal purposes:

1) The presentation of a positive cultural image of Islam and Muslims to the contemporary world

2) The deepening and promotion of commonalities in faith and patriotism among the inhabitants of one society

3) The protection of our societies from the dangers of extremism and the shielding of our youth from the culture of al-Qaeda

4) The contribution to the process of development and democratic change and the promotion of human rights

It remains for us now to confirm that this chronic weakness does not concern expertise or the meagerness of resources and support, nor weakness in empowerment and influence, nor the penetration of missionaries and preachers and religious luminaries. In fact the opposite is the case. The expertise, the resources and budgets dedicated to these people are huge and bloated. Political and popular support is considerable and growing all the time.

The extended reach of preachers and their influence is growing every day at the mosque pulpit, the satellite channel and at every level of social and institutional activity. So much so that the month of Ramadan has become a profitable season for preachers and shaykhs who are in no fear of any competition. Nevertheless this exalted religious discourse has been impotent to achieve any of its aims in knowledge, ethics, behaviour, growth or culture to boast of, or distinguish it from any other people of the contemporary world. The distressing, confusing question remains: what is the reason for this impotence?

How long will religious discourse remain a crisis-inducing factor in Islamic societies? The answer lies in analyzing this discourse and breaking down its contents in order to reveal that this impotence and defectiveness lie basically in the structure of religious discourse: that is, that the impotence stems from a deep structural weakness and defectiveness, and is not merely a formal defect to do with the utilization of cultural data in modern technology, as some exponents of the religious discourse claim. In fact religious discourse has made use of communication technology, and in an uncivilized way with loudspeakers which raise so much of a disturbing racket that some wish for power cuts so that they can get some rest. It has even led some ministries of religious endowments and religious affairs in several Arab Muslim countries to warn preachers and imams to adjust their loudspeakers, but to no avail.

‘Extremism’ is a basis element that cannot be separated from religious discourse

No one can match our societies in the misuse of modern western technology. See what our extremists have done with the internet: they have occupied it and uploaded onto thousands of sites the ugliest of man’s primitive instincts against any of his fellow men who may differ with him in sect, religion or political viewpoint – as opposed to what some have imagined, that the revival of religious discourse would take place through the renewal of the contents of this discourse to cover society’s contemporary issues.

The question of renewal, in my view, is something deeper, something more far-ranging and comprehensive than that. It is a question of the infrastructure of the discourse itself and its internal composition. By this I mean the extremist thinking which constitutes the basic source feeding this discourse, and which dominates its structure, composition and its basic sinews, whether this be a traditionalist Salafist discourse or a contemporary Islamic Awakening discourse as part of what is termed ‘political Islam’.

The extremist attitude and spirit are two constant, tenacious features of religious discourse in all its forms, levels and aspects, whether these be religious courses or religious education in the madrasa, the college or the faculty, or whether they be fatwas or discussions on satellite channels or websites. ‘Extremism’ is a basis element that cannot be separated from religious discourse and it manifests itself in contemporary religious discourse in three conspicuous aspects:

The male dominance attitude

Religious discourse in general is a male discourse monopolized by men alone, even in the most private female subjects. Women in religious discourse are constantly excluded entities, despite constant reference to them in fatwas and sermons, either as something to be warned against – her allure, her seductiveness and evil influence – or feared for. A caging is imposed upon her by society to keep here away from the current of life and social activities. As Mshari al-Dhaydi[1] puts it:

There is a sick sensibility vis-à-vis woman and any appearance she makes in public life, and indeed vis-à-vis her primary rights. She is an invisible being in politics, education, the media and the law. In every sphere of public and social life this being lives in the gloom of the tall walls of apartheid.

Woman in religious discourse is a being that is always condemned – even if she is a victim. In cases of rape and sexual harassment it is the woman that is blamed. The male perpetrator is let off since he is not expected to be able to resist her temptation and seduction. An Australian mufti[2] – now removed from his post – once described women as uncovered meat that tempts cats to gobble it up, and declared: “do we blame the cats for that?”

Woman in religious discourse is an emotional being that cannot behave or control herself. She is in need of the guardianship of a male (the walī) who controls her movements and behaviour in his capacity as a discerning, ‘rational’ being, one who inhibits her willfulness and her propensity to emotionality. Religious discourse still practices and promotes discrimination against women in her rights as a citizen to attain to leadership position, particularly in the judiciary. To this date there is only one Gulf state – Bahrain – that has allowed for the presence of a woman in the judiciary.

Declaring someone to be a traitor is the expectoration of a sick mentality

Similarly the religious discourse is against the granting of a woman who has married a foreigner – the right to transfer her nationality to her sons and spouse. In some Gulf societies religious discourse sets itself squarely against the teaching of national education for its female students, and against women driving cars, despite the billions of riyals expended annually on foreign drivers. The prevalent religious discourse doggedly insists that the wergild[3] of a woman should be half that of a man, on the grounds of the ‘consensus’ of the religious jurisprudents, and on the subject of ‘female circumcision’ locks horns with the state that has banned it and campaigned against it. Religious discourse sides with the male who wishes to cheat his wife and lie to her when he weds ‘another’, on the grounds that lying is permitted in this case! Can one who lies to his wife be trusted to occupy a position of leadership? He who cheats on his wife cheats on everyone else too, for the cheated woman rears an unhappy family and, in the end, an unhappy nation.

Broadly speaking, the prevailing religious discourse is apprehensive about anything that concerns women, from the moment she is born to her dying day. As the old saying goes:

A woman has ten pudenda: when she marries the husband covers up only one of them; the other nine remain until the time she dies when the grave covers them.

The accusation of disbelief / treachery method

Religious discourse by virtue of being a fanatical sectarian discourse sees itself as possessing absolute truth, whether this be in terms of religious creed or jurisprudential and political opinion. Consequently it casts doubt on the religious creed and intentions of another, on the grounds that there is one true creed and there is one ‘saved sect’. The creed of the others contains distortions, or errors or innovations. A large part of Salafist discourse is a fanatical discourse of accusations of disbelief against the Shī‘a and the Sufis. Just recently the Salafists in Kuwait rose up against Dr. Muhammad ‘Abd al-Ghaffār al-Sharīf[4] since he failed to describe as polytheists those who make processions around graves. A suicide bomber detonated himself in Karachi in the midst of thousands celebrating the Birth of the Prophet, injuring hundreds.

If a portion of Salafist discourse consists of accusations of disbelief against others, a portion of Sahwist (Islamic Awakening) discourse consists of accusations of treachery. To give some examples: the ‘treachery’ discourse of Hizbullah and Hamas and political Islamist groups and some of the Sahwist writers who impugn treachery to their opponents, particularly the liberals. Woe betide if you cross swords with a Sahwist on screen for if he proves inept there and his ideas bankrupt he will excommunicate you both from Islam and from the nation and accuse you of being a ‘collaborator’, and will not stint from exploiting the mosque to declare his opponents infidel and traitors.

Suggested Reading

We used to think that our societies, thanks to our religious discourse, had gone beyond slogans of ‘treachery’ and ‘infidelity’ and ‘collaborators’ predominant in the sixties in the age of Nasserism. This was until the provocateur discourse of these latter revived the memory of these slogans, and re-employed them. It gives evidence that our current religious discourse is resistant to treatment .

Declaring someone to be a traitor is the expectoration of a sick mentality of one who monopolizes ‘religion’ and ‘nationality’ to deny them to others in an act of totalitarian, authoritarian, egotistical presumption, one which expresses his level of intellectual bankruptcy and impotence. All peoples of the world have dispensed with it – save us. This is the tragedy of the prevailing discourse and it seems that the accusation of treachery and its exponents will only be stopped by a storm coming upon them.

The conspiratorial, accusatory view

In general the religious discourse is populated by the fantasies and fears of a world conspiracy. It sees the West as an implacable enemy from which nothing good can be expected and which is primarily responsible for the appalling conditions, the backwardness, the calamities and failures in growth, production and education that the Muslims are suffering. Consequently it fills the heads of our youth with hatred and dresses up for them suicide projects with the argument that “If the West has atomic bombs we have human bombs”. This is the extremist thinking which dominates current religious discourse, and which still prevents Muslims from offering a mature, rational, healthy discourse, reconciled both with itself and with the world.

[1] An influential columnist for the London-based al-Sharq al-Awsat newspaper. (Ed.)

[2] Shaykh Tāj al-Dīn al-Hilālī, once the top cleric at Sydney’s largest mosque and considered at the time the most senior Islamic leader by many Muslims in Australia and New Zealand. He has served as an adviser to the Australian government on Muslim issues. (Ed.)

[3] This is the correct (old) English lexical equivalent for دية , which refers to the fine or amercement paid as a composition for the shedding of blood. The modern term ‘blood money’ is ambiguous, since it has lost its legal definition and has associations with ‘contract killing.’ (Ed.)

[4] Dr. Muhammad ‘Abd al-Ghaffār al-Sharīf, the Secretary-General, Secretariat General of Religious Affairs in Kuwait is a signatory to the Amman Message promulgated in November 2004 which drew up a consensus of all Islamic denominations calling for tolerance and unity in the Muslim world. It focused on defining who a Muslim is; excommunication from Islam (takfīr), and principles related to delivering religious edicts (fatāwa). (Ed.)

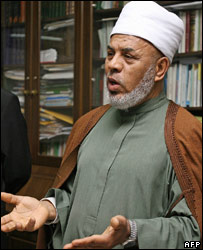

Main image: The aftermath of a suicide mob in a Karachi mosque