THERE ARE, at present, some excellent academic initiatives which prioritise textual criticism and apparatus criticus and are of major relevance to the issue of the transmission of the Qur’ānic text in the various maṣāḥif. There exist also various ‘alternative tafsirs’ that focus on Qur’ānic content that appears to conflict with contemporary values, or with contemporary science, medicine and cosmology. There is, however, no readily accessible commentary that focuses specifically on the editorial features of the text and on issues related to the compilation process: questions of philology, grammar, vocabulary, textual obscurity, syntax and anacoloutha – which have exercised Muslim scholars throughout the centuries. The aim of this Qur’ānic commentary is to highlight these issues as illustrated by the Almuslih authors, in just such an accessible format.

The Almuslih Qur’ānic Commentary is organised into two parts:

- Commentaries ordered by sūra

- Commentaries organised by theme

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39

40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59

60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79

80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99

100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114

For scholarly works on individual Qur’ānic sūras see Studies by Qur’ānic sūra

Editorial inconsistency, incoherence and repetition

Self-referentiality and scholarly polemics on editorship

Apostrophe and addressee

Anacoloutha and inconsequential passages

Issues of Arabic grammar

Sūras

Preliminary note

This index does not include textual variants which occur passim, such as the variations of short a and long ā, the later interpolations of superscript alif letters for the purposes of standardising the spellings, the elision of hamzat al-waṣl, the ‘open’ tā’ (ت) and the ‘bound’ tā’ (the tā’ marbūṭa – ة), and the conservative spellings of words such as حيوة ḥyū(h) for حياة ḥayā(h) or زكوة zakū(h) for زكاة zakā(h). On these issues, and their implications, see the Almuslih article The Qur’ānic script – some clarifications. For the disputed origins of the fundamental terms: Qur’ān, Islam, Muslim, dīn, Fārūq see the Almuslih article The meaning of ‘religion’ and ‘Islam’ in the Qur’ān.

1. الفاتحة al-Fātiḥa

The opening sūra of the Qur’ān has long puzzled commentators since as a work held to be the very words of God we have an address directed towards God: All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds. Master of the Day of Judgment. Thee do we serve and Thee do we beseech for help. The problem is highlighted with that phrase since God’s words would have to be Me do I serve and Me do I beseech for help which generates an absurdity. The absence of the word qul (‘Say’:) generally preceding such phrases, and the observation that there is confusion as to whether this is a Makkan or Madinan sūra, have led scholars deduce that this opening Sūrat al-Fātiḥa does not actually belong to the Revelation, but is a prayer affixed to it later.

2. البقرة al-Baqara

Verses 30-37 of this sūra contain examples of a sudden change in the identity of the speaker from I to We to He. The same change occurs at verses 49-53; 56-58 and 63-64.

The final word in the phrase at verse 124: My covenant includeth not wrong-doers is given as الظَّالِمِينَ al-ẓālimīn. Al-Ṭabarī and al-Zamakhsharī confirm that, as opposed to the now standard form, in some other Qur’āns – which ‘Uthmān had burned – the form of the word was al-ẓālimūn, making them the subject of the verb يَنَالُ yanāl (which can mean either ‘obtain’ or ‘reach’). Ibn Kathir in his commentary on this passage preferred not to mention the syntax of the verse.

Verse 246 features the verb عَسَيْتُمْ ‘asaytum (‘it may be that you’) which matches poorly with the sense of the text which would literally read: Is it that – it may be that – when fighting is prescribed for you. The verb verb عسى ‘asā used here is more likely عصى to give عصيتم ‘aṣaytum (‘disobey‘), rendering the more comprehensible phrase: Did you disobey when fighting was prescribed for you?

Verse 259 contains a curious exchange between Allah and a man who did not believe in the Resurrection, and who was incredulous that he had been made to sleep and arise again. To prove what He had done Allah says: Just look at thy food and drink which has not rotted! Look at thine ass! The non sequitur of the text of this command is explained as the result of the misreading of three words: حِمَارِكَ ḥimārik, يَتَسَنَّهْ yatasannah and طَعَامِكَ ṭa‘āmik, understood respectively as ‘thy ass’, ‘rot’ and ‘thy food’. He see ḥimārik as a misreading of a Syriac term ܓܡܪܟ gmārāḵ (‘thy perfection’), yatasannah as originally the Syriac ܐܫܬܢܝ eshtnī, which means ‘to change’ and ṭa‘āmik as ܛܥܡܬܟ ṭ‘amṯak meaning the ‘your mind’. The phrase would therefore mean: Look at your mind and your state: it has not changed! a phenomenon which, as the Qur’ānic verse goes on say, is something therewith we make you an example for the people.

3. آل عمران Āl ‘Imrān

Verse 61 of this sūra shows an editorial confusion, since the phrasing implies Muḥammad invoking a curse of Allah upon transgressors (and pray for the curse of Allah on the liars) rather than Allah ‘wishing’ – un-omnipotently – that His curse will come upon them. See also IX (al-Tawba), 30 and LXIII (al-Munāfiqūn), 4.

4. النساء al-Nisā’

Verse 16, which mentions the celestial reward in store both for the believers in that which is revealed unto thee, and that which was revealed before thee (i.e. the pre-Qur’ānic scriptures), was held by ‘Ā’isha to be ‘the work of the writers, who made mistakes in the Book’.

Verse 85 ends with the phrase Allah is mindful over all things. The verb in the text translated as ‘mindful’ is مُقِيتًا muqītan which actually means ‘loathsome’. Scholars and lexicographers such as the author of Lisān al-‘Arab Ibn Manẓūr had to redefine the word (used elsewhere in the Qur’ān to mean ‘loathsome’) as also meaning ‘mindful’ in order to exonerate the Qur’ān from the possibility of error. Whereas the original word must have been مثيبا muthīban (‘recompensing’) to make: Allah is recompensing in all things.

At verse 117 Allah deplores the acts of worship of Muḥammad’s enemies, that they invoke in His stead only females. The word إِنَاثًا ināthan translated as ‘idols’ actually means ‘females, and is likely a misreading of an original أوثانا awthānan (‘idols’).

5. المائدة al-Mā’ida

Verse 69 of this sūra which maintains that the Sabians number among the saved, was held by ‘Ā’isha to be ‘the work of the writers, who made mistakes in the Book’.

6. الأنعام al-An‘ām

Verse 99 demonstrates some editorial confusion in the sudden changes in the subject of speaker and changes in case endings to indicate the object of a verb: And He it is Who sends down water from the cloud, then We bring forth with it buds of all (plants) … and from the date-palm, from the pollen thereof, pendant bunches (قِنْوَانٌ دَانِيَةٌ qinwān-un dābiyat-un instead of قنواناً دابيةً qinwān-an dābiyat-an).

Verse 100 of this sūra reads the word خرق kharaq (‘breached’) to give the nonsensical passage: and they falsely breached Him sons and daughters. The original word must have been خلق (khalaq) ‘created’, to give: and they created for Him sons and daughters.

Verse 114 has the Qur’ān specifically speaking in the voice of Muḥammad as he addresses the Jews: Shall I then seek a judge other than Allah? And He it is Who has revealed to you the Book followed by an instant switch of subject: those whom We have given the Book know that it is revealed by your Lord (where one might have expected by us, indicating the ambiguity of who is speaking at this point).

7. الأعراف al-A‘rāf

In verse 145 of this sūra, which references Jehovah’s promise to Abraham to inherited the land of Canaan, the copyist appears to have misread an original سأورثكم sa-ūrithkum (“I will cause you to inherit”) as سأريكم sa-urīkum (“I will show you”).

The phrase in verse 149: And when they repented uses the verb سقط suqiṭa. The form does not sit well in a phrase that would literally mean and when it collapsed in their hands as an idiom for ‘repent. The proper, original form would have been أُسقط usqiṭa.

8. الأنفال al-Anfāl

9. التوبة al-Tawba

Verse 30 of this sūra shows an editorial confusion, since the phrasing implies Muḥammad invoking a curse of Allah upon transgressors (may Allah destroy them, How perverse are they! ) rather than Allah ‘wishing’ – un-omnipotently – that His curse will come upon them. See also III (Āl ‘Imrān), 61 and LXIII (al-Munāfiqūn), 4.

10. يونس Yūnus

11. هود Hūd

The first two verses of this sūra contains an example of a sudden switch of speaker that is difficult to view as a rhetorical device, since the phrase definitively indicates that it is Muḥammad who is speaking: This is a Book, whose verses are made decisive, then are they made plain, from the Wise, All-aware: Serve none but Allah. Lo! I am unto you from Him a warner and a bringer of good tidings.

12. يوسف Yūsuf

13. الرعد al-Ra’d

Verse 31 of this sūra is unfinished. The condition ‘if…’ is not answered with a ‘then …’. A phrase is missing, which the Pickthall translation has to duly supply in brackets (‘this Qur’an would have done so’) although this is not part of the Arabic text. The verb يْأَسِ yay’as which means ‘despair’ is taken by the commentators to mean ‘know’, whereas the original verb was likely يأنس ya’nus which does have this meaning.

14. إبراهيم Ibrāhīm

15. الحجر al-Ḥijr

16. النحل al-Naḥl

17. الإسراء al-Isrā’

The opening verse of this sūra runs: Glory be to Him Who made His servant to go on a night from the Sacred Mosque to the remote mosque (الْمَسْجِدِ الْأَقْصَى al-masjid al-aqṣā) which appears to contain a historical anachronism – this mosque was constructed after the period of ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān (r. 685-705) – suggesting a later editorial addition to the text following Muḥammad’s death.

Verse 64 runs: And startle whomsoever of them you can with your voice, and collect against them your mounted forces or your footsoldiers, and take part with them in their wealth and children. The sense indicates some editorial confusion has occurred and that this is due to misreadings from the unpointed Arabic words. The word أَجْلِبْ ajlib (‘collect’) is better read as اخلب akhlub (‘outwit’); بِخَيْلِكَ bi-khaylika (‘with your mounted forces’) as بحيليك bi-ḥiyalika (‘with your snares’), وَرَجِلِكَ wa-rajilika (‘your footsoldiers’) as ودجلك wa-dajalika (‘your deceitfulness’). The verb وَشَارِكْهُمْ wa-shārikhum (‘and take part with them’) is better explained as a misreading of the Syriac verb ܣܪܟ srk ‘to trick’ so that the phrase should mean ‘and trick them’. All of which gives a more cogent verse: And startle whomsoever of them you can with your voice, and outwit them with your snares or with your deceitfulness, and trick them with wealth and children.

18. الكهف al-Kahf

19. مريم Maryam

Verse 24 refers to the events of Mary’s giving birth to Jesus. The Qur’ānic text has the somewhat obscure phrase: Then one called out to her from beneath her: Grieve not, surely your Lord has made a stream to flow beneath you. The words for beneath her and stream are scribal misreadings of Syriac originals. The phrase مِنْ تَحْتِهَا min taḥtihā (‘from beneath her’) is a misreading of the letters من نحته which represent the Syriac ܡܢ ܢܚܬܗ men nḫāṯāh (‘from her delivery’) and سَرِيًّا sariyya (‘stream’) is from the Syriac word ܫܪܝܐ sharyā (‘lawful’, ‘legitimate’). The proper meaning of the Qur’ānic phrase is thus: Then he called to her after her delivery, do not grieve, your Lord has made your delivery legitimate’.

20. طه Ṭā Ḥā

Verse 41 here records God as addressing Moses with the words: I have attached you to Myself. The obscurity of his phrase is better explained if the verb ‘attached’ ( وَاصْطَنَعْتُكَ wa-ṣṭana‘tuka ) is a misreading of واصطفيتك wa-ṣṭafaytuka (‘selected’) to give the sense: I have selected you for Myself. This verb اصْطَفَىٰ iṣṭafā (‘select‘) is used elsewhere in the Qur’ān.

Verse 63, which mentions the phrase ‘most surely two magicians’ was held by ‘Ā’isha to be ‘the work of the writers, who made mistakes in the Book’.

The final verb at the end of verse 117 should be in the dual form, to correspond with the two subjects ‘thee and thy wife’ (which are followed with a correct dual form يُخْرِجَنَّكُمَا yukhrijannakumā – ‘let him not drive you both out’) but is instead is placed the singular form تَشْقَىٰ tashqā, (‘that ye both thou be unhappy’) in order to harmonise with the rhyme endings of this sūra.

21. الأنبياء al-Anbiyā’

Verse 98 the word حَصَبُ ḥaṣab used in the phrase Surely you and what you worship besides Allah are the firewood of hell is a transcriptional error for حَطَبُ ḥaṭab (‘firewood’). The author of Lisān al-‘Arab Ibn Manẓūr likely had to redefine the word as also meaning ‘firewood’ in order to explain this verse.

22. الحج al-Ḥajj

23. المؤمنون al-Mu’minūn

24. النور al-Nūr

25. الفرقان al-Furqān

26. الشعراء al-Shu‘arā’

27. النمل al-Naml

28. القصص al-Qaṣaṣ

29. العنكبوت al-‘Ankabūt

30. الروم al-Rūm

31. لقمان Luqmān

Verses 13-17 demonstrate evidence of some inept editing as two verses, whose subject is Allah, appear to be arbitrarily inserted into a dialogue between Luqmān and his son: O my son! do not associate aught with Allah … And We have enjoined man in respect of his parents … And if they contend with you that you should associate with Me what you have no knowledge of, do not obey them … O my son! surely if it is the very weight of the grain of a mustard-seed … O my son! keep up prayer.

32. السجدة al-Sajda

33. الأحزاب al-Aḥzāb

The ending of verse 66 – الرَّسُولَا al–rasūlā – gives an example of the requirements of the rhyme sequence dictating the form of the Qur’ānic word. The final alif (forming the ā) in the word was added, unnecessarily, to harmonise with the earlier verse endings: sa‘īra(n) – naṣīrā(n). Since the word (unlike the preceding two rhymes) is a definite noun the extra alif is redundant.

34. سبإ Saba’

35. فاطر Fāṭir

Verse 9 demonstrates some editorial confusion in the instant switch of subject of the speaker in mid-sentence: And Allah, Who sends the winds so they raise a cloud, then We drive it on to a dead country.

36. يس Yā Sīn

37. الصافات al-Ṣāffāt

38. ص Ṣād

39. الزمر al-Zumar

In verse 10 of this sūra the phrase O my slaves who believe! be careful of (your duty to) your Lord … contains a blasphemous statement, implying that the believers are slaves to Muḥammad instead of to Allah. The same applies in verse 53 where the phrase O my slaves ... is repeated. In either case, the editorial prefixing of the word qul (‘Say’) does not remove the confusion on the text, since the blasphemy persists if the phrase were Allah speaking the words: Say: O my servants! who have acted extravagantly against their own souls …

40. غافر Ghāfir

41. فصلت Fuṣṣilat

42. الشورى al-Shūrā

Verse 25 of this sūra has a misplaced preposition. The sentence which is translated as He it is Who accepts repentance from His servants should according to the Arabic text actually read: He it is Who accepts repentance on behalf of ( عن ) His servants. The preposition عن ‘an has here been mistakenly written for من min.

43. الزخرف al-Zukhruf

44. الدخان al-Dukhān

Verse 54 mentions the حُورٌ عِينٌ ḥūr ‘īn, the ‘wide-eyed’ beauties (familiarised in the term houris) that await the blessed believers in Heaven. On this see entry for sūra 56.

45. الجاثية al-Jāthiya

Verse 21 of this sūra has the word اجْتَرَحُوا ijtaraḥū standing for those who ‘commit’ ill-deeds, which contradicts the Arabic lexicon. It is a scribal misreading of the word اقترفوا (iftaraqū) misreading the letters f and q as j and ḥ.

46. الأحقاف al-Aḥqāf

47. محمد Muḥammad

48. الفتح al-Fatḥ

49. الحجرات al-Ḥujurāt

50. ق Qāf

51. الذاريات al-Dhāriyāt

52. الطور al-Ṭūr

Verse 20 mentions the حُورٌ عِينٌ ḥūr ‘īn, the ‘wide-eyed’ beauties (familiarised in the term houris) that await the blessed believers in Heaven. On this see entry for sūra 56.

Verse 24 repeats the sentiment of sūra 76 where one of the joys of paradise is youths like scattered pearls serving the blessed believers. The reference to ‘youths’ is a misinterpretation of ‘newborn, fresh fruits’. See entry for sūra 76.

53. النجم al-Najm

54. القمر al-Qamar

Verse 16 of this sūra shows how the compiler(s) adjusted the text and Arabic grammar in order to artificially preserve the rhyme sequence. In the phrase فَكَيْفَ كَانَ عَذَابِي وَنُذُرِ fa-kayfa kāna ‘adhāb-ī wa-nudhur (‘So how (great) was My punishment and my warning!’) the personal ending -ī was left off from the final word nudhur, in order to maintain the rhyme sequence of the verses which end in the letter r: dusur – kufir – muddakir – nudhur. It is not a single lapse, since this word form is repeated five times in the sūra.

55. الرحمن al-Raḥmān

In verse 56 the word يَطْمِثْهُنَّ yaṭmithhunna, understood to mean ‘touched them’, is a scribal misreading of يطئهن yaṭa’uhunna (‘have sexual intercourse with them’) due to the absence of diacritical dots in the early manuscripts. Yaṭmithhunna actually means menstruating, and subsequent scholars have attempted to attach the new meaning of ‘touched’ to render the passage comprehensible.

56. الواقعة al-Wāqi‘a

Verse 22 speaks of the حُورٌ عِينٌ ḥūr ‘īn, the ‘wide-eyed’ beauties (familiarised in the term houris) that await the blessed believers in Heaven. The word ḥūr does not come from the Arabic adjective أحْوَر aḥwar (pl. حور ḥūr) but in fact represents ܚܘܪܐ ḫewwārā a Syriac adjective for white grapes and that the word ‘ayn is a nominal adjective expressing purity. The image is derived from Syriac Christian imagery such as that in the Mīmrā ‘On Paradise’ composed by Ephrem the Syrian (306-373 AD). The term is also reprised in sūras 52:20 and 44:54.

57. الحديد al-Ḥadīd

58. المجادلة al-Mujādila

Verse 11 of this sūra has the curious instruction: when it is said unto you, ‘Make room!’ in assemblies, then make room. The imperative verb ‘make room’ here is انْشُزُوا inshuzū which means ‘arise’. The original word must have been انتشروا intasharū (‘disperse’) to make the phrase: And when it was said, ‘disperse’ they dispersed.

59. الحشر al-Ḥashr

60. الممتحنة al-Mumtaḥana

61. الصف al-Ṣaff

62. الجمعة al-Jumu‘a

63. المنافقون al-Munāfiqūn

Verse 4 of this sūra shows an editorial confusion, since the phrasing implies Muḥammad invoking a curse of Allah upon transgressors (may Allah destroy them, How perverse are they! ) rather than Allah ‘wishing’ – un-omnipotently – that His curse will come upon them. See also III (Āl ‘Imrān), 61 and IX (al-Tawba), 30.

Verse 10, which contains the passage: If only thou wouldst reprieve me for a little while, then I would give alms and be among the righteous was held by ‘Ā’isha to be ‘the work of the writers, who made mistakes in the Book’.

64. التغابن al-Taghābun

65. الطلاق al-Ṭalāq

66. التحريم al-Taḥrīm

67. الملك al-Mulk

68. القلم al-Qalam

69. الحاقة al-Ḥāqqa

Verse 3 highlights the obscurity of the word Ḥāqqa which the compiler(s) left unsolved with the phrase: Ah, what will convey unto thee what the ḥāqqa is?

70. المعارج al-Ma‘ārij

71. نوح Nūḥ

72. الجن al-Jinn

73. المزمل al-Muzzammil

In Verse 20 of this sūra – held to be the third sūra revealed to Muḥammad – the phrase and others who fight in Allah’s way … and keep up prayer and pay the poor-rate seems to indicate that the author or transcriber of the Qur’ān has either inserted a Madinan sūra by mistake, or has committed an anachronism, given that fighting was not prescribed for Muslims until after Muḥammad had migrated to Madina. Nor was prayer imposed on Muslims until the tenth year following the initiation of the Message, while zakāh was only imposed at the end of Muḥammad’s life in Madina.

74. المدثر al-Muddaththir

The word ‘trumpet’ ناقور nāqūr in verse 8 was imposed by the rhymes at this passage which were ending in ‘r’ whereas the commonly used word for this was the nāqūs bell of the Christians. Later, at verse 22 the word بَسَرَ basara appears to have been similarly used to maintain the saj’ rhyme sequence (qadara – naẓara – basara) of this passage. The same applies to the use of the word سقر saqar, a term entirely unfamiliar to Arabs and which needed a textual gloss woven into the Qur’ān itself.

The dictates of rhyme also appear to have determined the verses 29-30, where the phrase لَوَّاحَةٌ لِلْبَشَرِ عَلَيْهَا تِسْعَةَ عَشَرَ lawwāḥatun lil-bashar – ‘alayhā tis‘ata ‘ashar (It scorches the mortal. Over it are nineteen) has long perplexed the commentators as to its meaning, which is not resolved by a following And We have fixed their number only as a trial for Unbelievers.

Verses 49-51 contain the following odd simile: What is then the matter with them, that they turn away from the admonition, as if they were asses taking fright and fleeing from a lion? The word translated as ‘lion’ is قسورة qaswara, which the Muslim scholars described as a loan-word from Abyssinian. The Arab commentators were actually reading a Syriac word ܩܣܘܪܐ qāsōrā meaning ‘decrepit donkey’. So the correct sense of the Qur’ānic verse is: ‘Why then should wild asses flee from an old donkey?’ which makes more sense as an idiom in this context.

75. القيامة al-Qiyāma

Verse 14 shows signs of a grammatical mistake. in the phrase بَلِ الْإِنْسَانُ عَلَىٰ نَفْسِهِ بَصِيرَةٌ Bal al-insānu ‘alā nafsihi baṣīratun (‘Nay! man is perceptive (witness) against himself‘) the adjective baṣīratun (‘perceptive’) is in the feminine form, whereas the word for man (insān) is masculine. The mistake is likely due to the preceding word nafsihi being a feminine noun.

76. الانسان al-Insān

Verse 19 speaks of one of the joys of paradise where round about them shall go youths never altering in age; when you see them you will think them to be scattered pearls. The terms ‘youths’ and ‘never altering in age’ are misreadings of original Syriac terms deriving from Syriac texts known as Mīmrē such as those composed ‘On Paradise’ by Ephrem the Syrian (306-373 AD). For وِلْدَانٌ wildān (‘youths) the Syriac figurative meaning of ‘newborn’, ‘fresh’ from ܝܠܕܐ yaldā ‘newborn’ is the likely origin, and for مُخَلَّدُونَ mukhalladūn (‘eternal’, ‘never altering in age’) a more correct reading is likely to be مجلدون mujalladūn (‘chilled’). The text should therefore read as: Chilled fresh fruits pass around among them; to see them, you would think they were loose pearls.

77. المرسلات al-Mursalāt

78. النبإ al-Naba’

79. النازعات al-Nāzi‘āt

80. عبس ‘Abasa

Verse 31 of this sūra presented the followers of Muḥammad, including Abū Bakr, with a puzzle as to what the word وَأَبًّا abba meant in a context of God’s providing of foods for mankind and his animals. The word abb comes from a Syriac word ܐܒܒܐ ebba meaning ‘ripe fruit’ or ‘the produce of the earth’.

81. التكوير al-Takwīr

82. الإنفطار al-Infiṭār

83. المطففين al-Muṭaffifīn

Verse 8 highlights the obscurity of the word Sijjīn which the compiler(s) left unsolved with the phrase: Ah, what will convey unto thee what the Sijjīn is?

Verse 19 has the same problem with the word ‘Illiyyūn which the compiler(s) similarly left unsolved: Ah, what will convey unto thee what ‘Illiyyūn is? It appears to derive from the Hebrew term עֶלְיוֹן ‘elyōn ‘most highest’ featured in Isaiah 14:13–14, 2 Samuel 22:14 and Psalms 97:9.

84. الإنشقاق al-Inshiqāq

85. البروج al-Burūj

86. الطارق al-Ṭāriq

Verse 2 highlights the obscurity of the word Ṭāriq which the compiler(s) left unsolved with the phrase: Ah, what will convey unto thee what the Ṭāriq is?

87. الأعلى al-A‘lā

88. الغاشية al-Ghāshiya

89. الفجر al-Fajr

90. البلد al-Balad

Verse 12 highlights the obscurity of the word ‘aqaba which the compiler(s) left unsolved with the phrase: Ah, what will convey unto thee what the ‘aqaba is?

91. الشمس al-Shams

92. الليل al-Layl

93. الضحى al-Ḍuḥā

94. الشرح al-Sharḥ

95. التين al-Tīn

The oath that initiates this sūra: I swear by the fig and the olive, and by Mount Sinai, and by this city made secure has a rhyme sequence (ūn – īn – īn) that makes the word for ‘Sinai’ difficult to fit into. Accordingly the name is arbitrarily altered into سِينِينَ Sīnīn to make it fit.

96. العلق al-‘Alaq

Regarded as the first sūra revealed to Muhammad, the issue around the phrase Read! in the name of your Lord which the scholars wrestled with was who was being addressed, given that the tradition holds it that Muhammad was illiterate. In addition, there is the statement He created man from a clot which conflicts with the order given elsewhere in the Qur’ān: first the sperm-drop (al-nuṭfa), then a chewed piece (al-muḍgha), and then a clot (al-‘alaqa). It is likely that ‘alaqa (clot) was set as the origin of human life because it satisfied the need to maintain the rhyme (khalaq – ‘alaq)

A further contradiction in this sūra is the phrase Have you seen him who forbids a slave when he prays? This statement comes in what is the first sūra that was revealed to Muḥammad, when the act of prayer was yet to be instituted as an obligation.

Verse 15 has a curious ungrammatical form لَنَسْفَعًا lanasfa’an for what should be لَنَسْفَعن nasfa‘anna (‘We would certainly smite him‘).

97. القدر al-Qadr

98. البينة al-Bayyina

99. الزلزلة al-Zalzala

100. العاديات al-‘Ādiyāt

101. القارعة al-Qāri‘a

Verse 3 highlights the obscurity of the word qāri‘a which the compiler(s) left unsolved with the phrase: Ah, what will convey unto thee what the qāri‘a is?

102. التكاثر al-Takāthur

103. العصر al-‘Aṣr

104. الهمزة al-Humaza

105. الفيل al-Fīl

106. قريش Quraysh

107. الماعون al-Mā‘ūn

108. الكوثر al-Kawthar

The sūra opens with the statement: Surely We have given you Kawthar. So pray unto thy Lord, and sacrifice. The term kawthar has been traditionally understood to mean ‘Abundance’ and suggested as a name for a river in Heaven. While the verbal root k-th-r is common to both Arabic and Syriac, in Arabic it denotes ‘to be much, many’ while in Syriac it denotes ‘to remain, last’. The phrase is more correctly understood as: Surely We have ordained for you lasting prayer. So pray unto thy Lord, and sacrifice.

109. الكافرون al-Kāfirūn

110. النصر al-Naṣr

111. المسد al-Masad

112. الإخلاص al-Ikhlāṣ

113. الفلق al-Falaq

114. الناس al-Nās

Themes

The ordering of the sūras

According to the doctrine of the Preserved Tablet (al-Lūḥ al-Maḥfūẓ – See Glossary) the sūras must have been ordered primordially. Yet the heritage works indicate that Muḥammad gave instructions as to where and in what sūra a new verse was to be inserted. In addition, a sūra such as al-Baqara was revealed over a period of six years. What adds to the confusion is that when Zayd ibn Thābit put together the Qur’ān, he did not follow the revelation of the sūras in their historical sequence, but ordered them according to their length. This, some have argued, is because Muslim scholars had difficulty in discerning a thematic or chronological order for the Qur’ānic sūras.

The text of the Qur’ān is characterised by a multitude of repetitions and sentences that appear detached from their context. For some, this indicates that the text was not adopted in the form it takes at present all at once, but went through many stages of writing, editing and recording by editors importing into the process their various perceptions. The Islamic tradition itself recognizes that the Qur’ān is a product of composition and the traditional understanding of the sūras as being divided between Makkan and Madinan revelations also accommodates the phenomenon of Makkan sūras as containing Medinan verses that were added later. This implies the idea of the sūras being rewritten several times.

There is also an ambiguity in the Islamic tradition that holds that Muḥammad was the one who determined the exact location and position of the verse in the Qur’ān, while at the same time maintaining that the complete codification of the Qur’ān was carried out after his death. For instance, the Islamic tradition preserves the account of Ḥuzayma ibn Thābit informing ‘Umar ibn Al-Khaṭṭāb that some verses had been omitted from the compilation process, and ‘Umar asking: “Where do you propose that we should put them?’ He replied: ‘Put them as the last two verses of the Qur’ān’. And he put them at the end of sūrat al-Barā’a (al-Tawba).” Abū Bakr bin Abī Dā’ūd al-Sijistānī records ‘Uthmān as saying: “You have carried this out well and with euphony. I can see a number of errors, but the Arabs may correct these themselves on their tongues”.

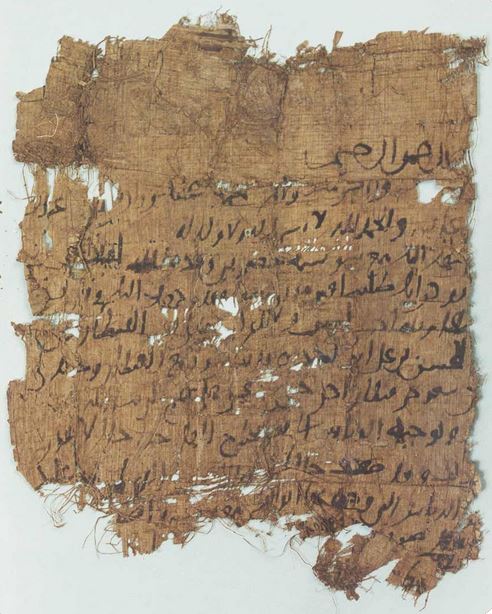

Islamic tradition in the main holds that the Qur’ān and hadith were committed orally to memory from the time of Muḥammad until the tenth century thanks to professional ‘memorisers’ (al-ḥafaẓa) who transmitted the official text to each other without writing it down. With the expansion of the Muslim conquests, rulers began to fear that the memorisers would perish in the battles and wars, and so urgent efforts were made to have the passages preserved in written form. There is, however, no agreement as to when the Qur’ānic text was written down. Dates range between the supposed era of Muḥammad (622–632), the reign of the Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (644–656), the reign of Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān (685–705), and the ‘Abbāsid period in Damascus (657–750). Some scholars postpone the final writing of the Qur’ān to the ‘Abbāsid state at Baghdad (750-870) or even the tenth century. The date of creation of a fixed text continues to exercise Qur’ānic scholarship.

Several works focussing on the ordering of the sūras in the Qur’ān are also available in the Almuslih Library: see, for example, Aldeeb, S: القرآن الكريم بالتسلسل التاريخي للنزول وفقا للأزهر ; Frolov, D : Medieval Muslim Discussions about the Order of Suras and Their Relevance for the Study of the Composition of the Qur’an ; Mirza, U: The Chronological Koran, With the Original Biography of Mohammed, his Traditions, Letters, Treaties, and the Sharia Law ; Reynolds, G: Le problème de la chronologie du Coran ; Shakir, M: Chronological Qur’ān, The Meaning in English ; Stefanidis, E: The Qur’ān Made Linear: A Study of the Geschichte des Qorāns’ Chronological Reordering.

Abrogation

That there are passages in the Qur’ān that appear to stand in contradiction to each other exercised the endeavours of scholars from the earliest periods of Islam. The Qur’ān, self-referentially, appears to incorporate into the body of its Text the echoes of disputation in verses such as: Whatever communications We abrogate or cause to be forgotten, We bring one better than it or like it [Qur’ān II (al-Baqara), 106]. The number of such abrogated verses identified by Muslim scholars varies from 42 to 231.

Early historians and Qur’ānic commentators record the ambiguity that this concept presented to the Quraysh, who stated: “Do you not see how Muḥammad issues an order to his Companions today that he retracts tomorrow?” and the Qur’ān’s response: And when We change (one) communication for (another) communication – and Allah knows best what He reveals – they say: You are only a forger. Nay, most of them do not know [Qur’ān XVI (al-Naḥl), 101].

But these abrogated verses bequeathed a centuries-long controversy. A primary focus of this controversy was the problem that abrogation was generating for the principle of the ‘eternal Qur’ān preserved as a glorious Qur’ān on a Guarded Tablet‘ [Qur’ān LXXXV, 21-22] see Glossary). This principle explicitly contradicts the possibility of change or replacement, for there is none who can alter His words [Qur’ān XVIII (al-Kahf), 27]. If abrogation occurs, the controversy ran, the verses were therefore not on the Guarded Tablet. Dr. Naṣr Abū Zayd pointed out the problems that abrogation caused, and contemporary scholars have seen abrogation – with its tripartite division of a) verses ‘where the ruling was abrogated but their recitation remains’; b) verses ‘whose recitation was abrogated while their ruling remains’ and c) verses ‘whereby their ruling as well as their recitation are abrogated’ – as an intellectual device allowing traditional scholars to accept invalidation without at the same time engaging in evaluation.

Nevertheless, under the influence of the verse This day have I perfected your religion for you [Qur’ān V (al-Mā’ida),3] the consideration that the process of revelation halted with the death of Muḥammad led legislators to conclude that the ruling of an abrogating verse was something sacrosanct, and therefore consolidated. It effectively adduced the Qur’ānic verses which justified abrogation as God’s final word on the matter, one that cannot itself be ‘abrogated’.

Self-referentiality and scholarly polemics on editorship

The Qur’ān text on several occasions refers to itself as if it were something separate, not only as a ‘reading’ or ‘recitation’ (قُرْآنٌ qur’ān) but also as a ‘scripture’ (كتاب kitāb) ‘scripture’, ‘or as a ‘remembrance’, ‘recollection’ ( ذكر dhikr ).

This is naught else than a reminder (dhikr) and a reading (qur’ān) making plain [Qur’ān XXXVI (Yā Sīn), 69]

We have revealed the scripture (kitāb) to thee in Truth, for mankind [Qur’ān XXXIX (al-Zumar), 41]

What is interesting is the way that one seems to hear echoes of ongoing discussions about the Text incorporated into the fabric of the Text itself. One issue in dispute appears to be the incomprehensibility of many passages in a Text that claimed to have been issued in ‘clear Arabic speech’ and was claiming to be the final Revelation to mankind. The Text goes on the defensive:

It is He who has sent down to you, [O Muhammad], the Book; in it are verses [that are] precise – they are the foundation of the Book – and others unspecific. As for those in whose hearts is deviation [from truth], they will follow that of it which is unspecific, seeking discord and seeking an interpretation [suitable to them]. And no one knows its [true] interpretation except Allah . But those firm in knowledge say, “We believe in it. All [of it] is from our Lord.” And no one will be reminded except those of understanding. [Qur’ān III (Āl ‘Imrān), 7]

The Text here is talking about people reading this Text. It appears to be a commentary (perhaps from an Islamic jurist) and the confusion of the scholarly melee is immediately evident in the contradictions that the passage commits. Is the entire Qur’ān clear and fully explained, or are there parts of it which are unclear and whose interpretation only Allah knows? It goes on to state that only Allah knows the meaning of these difficult allegorical verses in the Qur’ān, but then contradicts this by stating that the ‘men of understanding’ can indeed grasp it.

The Text is at pains to inform the reader of its high quality (This is indeed a noble Qur’ān [Quran LVI (al-Wāqi‘a), 77]) and is also insistent on defending itself against some specific editorial criticisms. These include accusations that the Qur’ān lacks a coherent narrative structure:

We will recount to you the best of narratives in what We have revealed to you of this Qur’ān, and indeed prior to it you were among those who are unaware [Qur’ān XII (Yūsuf), 3]

And We have arranged it in the best arrangement [Qur’ān XXV (al-Furqān), 32]

and that it demonstrates internal contradictions:

If it had been from other than Allah they would have found therein much incongruity [Qur’ān IV (al-Nisā’), 82]

A frequent defence is made in response to criticism as to its authenticity as a revelation:

Or do they say, “He has forged it”? Say: “Do they say, ‘He has fabricated it’? [Qur’ān XXXII (al-Sajda), 3]

And if he had fabricated against Us some of the sayings, We would certainly have seized him by the right hand, then We would certainly have cut off his aorta. [Qur’ān LXIX (al-Ḥāqqa), 44-46]

This is truly a decisive discourse and it is no joke [Qur’ān LXXXVI (al-Ṭāriq), 13-14]

And the defense frequently takes on an aggressive tone:

So, leave those who reject this discourse to Me! [Qur’ān LXVIII (al-Qalam), 44]

There is also a hint of controversy stirred by Muḥammad making mention of ‘my slaves’ in verses such as:

Say: “O my slaves who believe! be careful of (your duty to) your Lord …” [Qur’ān XXXIX (al-Zumar), 10]

Say, “O My slaves who have transgressed against themselves [by sinning], do not despair of the mercy of Allah …” [Qur’ān XXXIX (al-Zumar), 53]

Whether or not the word ‘Say’ is original to these verses or a later addition, the potential blasphemy is not entirely removed, since the formula should have read: Say: “O slaves of Allah who …”. A verse in sūrat Āl ‘Imrān seems to further address this controversy with something of a fuller retraction:

No person to whom God had given the Scripture, wisdom, and prophethood would ever say to people, “Be my servants, not God’s.” Rather [he would / did say]: “You should be devoted to God because you have taught the Scripture and studied it closely.” [Qur’ān III (Āl ‘Imrān), 79]

The question of the poetic form of the pagan kuhhān appearing in some of the Makkan texts also seems to have been compromising, prompting Muḥammad’s rebuttal against his aspiring to be a ‘poet’. (On this question of Muḥammad attempting poetry, in order to conform to the Arabs’ perception of a prophet issuing gnomic utterances, see the Almuslih article: The saj‘-rhymes in the Qur’ān).

In the end, the defenders of the Qur’ān appeared to tire of the debate:

O ye who believe! Ask not questions about things which if made plain to you, may cause you trouble … Some people before you did ask questions, and on that account lost their faith. [Qur’ān V (al-Mā’ida), 101-102]

Finally, there are also some fascinating indications that what were once marginalia, such as instructions for reciters of the Text, or comments made by preachers during their sermons, have been inadvertently incorporated into the divine Text itself:

O, people, here is a parable, so listen carefully! [Qur’ān XXII (al-Ḥajj), 73]

Do not move your tongue with it to make haste with it; Surely on Us (devolves) the collecting of it and the reciting of it.; / When we recite it, repeat the recitation; / Then it is up to us to explain it [Qur’ān LXXV (al-Qiyāma), 16-19]

So, when the Qur’ān is recited, listen to it, and keep silence, so that you will obtain mercy. [Qur’ān VII (al-Aʿrāf), 204]

Several works focussing on the Qur’ān’s self-referentiality are available in the Almuslih Library: see, for example, Nicolai Sinai’s Qurʾānic Self-Referentiality as a Strategy of Self-Authorization). See also, Anne-Sylvie Boisliveau’s Canonisation du Coran… par le Coran ? (‘Canonization of the Qur’ân… by the Qur’ân?’) and her Polemics in the Koran. The Koran’s Negative Argumentation over its Own Origin.