2.The theory of the roots of the Syriac-Christian Qur'an. This theory holds that a large part of Qur’ānic texts were songs, Christian devotionals, hymns, supplications and prayers written in Syriac by the people of the Levant. They were written by Christian monks in the sixth century AD before the emergence of Islam. This was demonstrated by the German orientalist scientist Günter Lüling. After him a Syriac researcher of German origin Christopher Luxenberg (a pseudonym) uncovered the existence of many Syriac phrases and texts between the lines of the Qur’ān.

ONE OF THESE Syriac terms includes the word Qur’ān itself and its linguistic origin as a term distorted from the Syriac ܩܪܝܢܐ (Qeryānā) denoting a book of sermons or prayers and supplications summarizing the sermons and lessons of the Christian Gospels. The Qur’ān itself acknowledges, in sūra XXXVI (Yā Sīn) 69, that it is a recollection of sermons from the Torah and the Gospel when it says:

This is naught else than a Reminder and a Lecture (قُرْآنٌ Qur’ān) making plain.

One of the Syriac words in the Qur’ān that puzzled Muslim scholars was the word kawthar:

Surely We have given you Kawthar, Therefore pray to your Lord and make a sacrifice. Surely your enemy is the one who shall be without posterity.[1]

Muslim scholars made many suggestions for the meaning of the word al-Kawthar, all of which are wrong since they were ignorant of the Syriac language in which the Qur’ān was written. Since they did not understand its meaning they diligently came up with erroneous interpretations. Some said, without evidence, that it was the name of a river in Paradise, while others interpreted it as an ‘abundance’ of goodness, or an ‘abundance’ of followers, or the light in the heart of the Prophet, and so on. The interpretation given in the commentary Al-Jalalayn runs: ‘The abundant goodness of the prophecy, the Qur’ān and intercession’. All such interpretations were individual initiatives without any evidence to support them.

The Syriac meaning of al-Kawthar is ‘continuous worship’.[2]

As for the phrase Surely your enemy is the one who shall be without posterity (shāni’aka huwa al-abtaru) this in Syriac means ‘Satan is the cut off one’ that is, the defeated one who turns a person way from worshipping.

The Qur’ān never actually mentions the word ‘Christians’ but rather Naṣārā because it did not want to honour them with the word ‘Christ’

Another evidence for the existence of Syriac orthography in Qur’ānic words is the term زكاة zakāt which is written in Qur’ānic manuscripts as زكوة zakūt, and the form ṣalūt for the word ‘prayer’. In Syriac the terms are written ܙܟܘܬܐ zakūṯā and ܨܠܘܬܐ ṣalūṯā. This Syriac form of writing highlights how the Qur’ān is Syriac in spelling and meaning, due to the fact that the first copies were written by Syriac monks skilled in writing at a time of Islamic ignorance.

The way the verses of the Qur’ān were written developed according to the circumstances of the relationship between Muhammad and the People of the Book[3] who refused to abandon their religion and follow the religion of Muḥammad. Against these he waged in the Qur’ān hostility and a war of words. The Qur’ān considered the Christians – which it labelled Naṣārā – ‘polytheists’ since, according to Muḥammad’s belief, they ascribed shared partners to God.

The Qur’ān never actually mentions the word ‘Christians’ but rather Naṣārā because it did not want to honour them with the word ‘Christ’. The Qur’ān nevertheless calls for Jews and Christians to be fought. And some might therefore ask: if the Qur’ān is a Christian book, why would it slander Christians, fight them, call them ‘disbelievers’ and ‘polytheists’? Why are they called Naṣārā and not Christians? Some have responded to this question by saying that those who wrote the Qur’ān were Christian heretics, that is: Christianized Jews who rejected the Christian Trinity (the Father – the Son – the Holy Spirit) and were Arians or Nazarene Jews who had been expelled from the original Church.

3.The theory of the ‘Abbāsid Qur’an

This theory was proposed by the American historian and researcher John Wansbrough’. He maintains that the ‘Abbāsid caliphs requested a group of authors to write down religious tales taken from the stories and sermons of the Torah and the Gospels, with the aim to formulate a new religion, the religion of an early Islam close to Judeo-Christianity.

To give a sacred character to this man-made work, ‘Abbāsid jurists invented a personality called the Prophet Muḥammad bin ‘Abdullah. They concocted stories about Makka and the tribe of Quraysh, tales of Islamic conquests and the Prophet’s conquests. The American researcher held that the texts of the Qur’ān appeared only in the eighth century AD after the ‘Abbāsids had transferred from Khorasan to Baghdad. The earliest extant complete copy of the Qur’ān is the al-Mashhad al-Husaynī copy in Cairo which dates back to the late ninth century AD – corresponding to the third century of Hijra. This is the muṣḥaf of ‘Uthmān. There are also some other old Qur’āns, including the Qur’ān of San‘ā’ which is the oldest of all known copies, and there are also copies at Birmingham and Paris, but these are incomplete Qur’āns. Another ancient Ottoman Qur’ān is housed in a museum in Istanbul.

The Qur’ān appeared in a mixed language of old Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac along with Ethiopic and Persian words

The Qur’ānic language used in the copies is a mixture of several Arabic languages, ancient Levantine Arabic, Syriac, Hebrew, Ethiopic and Persian words, and even the word Gospel taken from its Greek form.[4]

4- The theory of the Judaeo-Christian Qur’ān

The proponents of this theory hold that the first Qur’ān emerged in the form of separate leaves, and they reject the narration of the ‘Abbāsid fuqahā’ and instead maintain that those who wrote the Judaeo-Christian Qur’ān were a sect of Christianised Jews who lived isolated in monasteries in the Levant. They belonged to a Jewish sect that broke away from the Rabbinic school of Judaism. They believed in Christ as the ‘servant of God and His Messenger’ and rejected any kind of divinity associated with him. They were called Naṣārā as in the Qur’ān or the Ebionite sect.[5] They were not the same as the Christians that have today spread over the world.

Suggested Reading

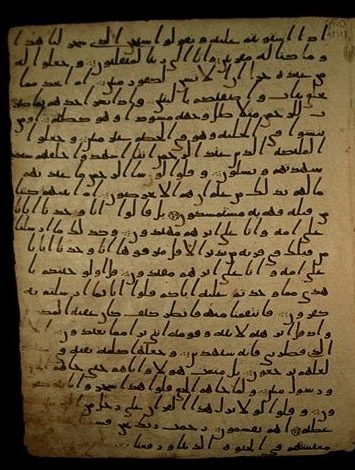

Why were the monks the first to write down the Qur’ān? The answer to this is that they were the only ones who possessed the linguistic skills or religious credentials and who were familiar with the stories of the prophets, and had the time to carry out these difficult tasks. To aid them they formulated a new Arabic orthography – the so-called ‘Hijazi script’ – that was not provided with diacritical dots. This was the first script in which the earliest Qur’ān was written and which subsequently developed.

The monks translated texts from the Torah and the Gospels from their original Hebrew and Greek into Arabic. This is why the Qur’ān appeared in a mixed language of old Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac along with Ethiopic and Persian words. By virtue of their presence in the Levant, the Judeo-Christians spoke the Syriac Aramaic used in the Levant. The long sūras such as Al-Baqara, al-Nisā’, al-Mā’ida and Āl ‘Imrān formed the first, Judaic, basis of the Qur’ān. These texts in these sūras were directed against Christians and against the Jews of Jerusalem.

[1] Qur’ān CVIII (al-Kawthar), 1-3.

[2] Luxenberg’s argument for this is that while the verbal root k-th-r is common to both languages, in Arabic it denotes ‘to be much, many’ while in Syriac it denotes ‘to remain, last’. See C. Luxenberg, The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran, Verlag Hans Schiler, p.295. For this work see the Almuslih Library, under the rubric: The Qur’ānic Vorlage Thesis. (Ed.)

[3] That is, non-Muslims who are adherents to faith which have a revealed scripture. See Glossary: ‘Ahl al-Kitāb’. (Ed.)

[4] The Arabic word for Gospel – Injīl – is ultimately derived from the Greek εὐαγγέλιον euangélion, but as Arthur Jeffery indicates in his Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur’ān (p.71) the form is likely derived more directly from the Syriac transcription ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ or, less likely, אוונגליון . See the Almuslih Library for Arthur Jeffery’s book The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur’ān is available at the Almuslih Library. (Ed.)

[5] The term Ebionite’ comes from the Hebrew אֶבְיוֹנִים ʾEḇyōnīm meaning ‘poor ones’ since they viewed poverty as a blessing. (Ed.)

Main image: An Early Qur’ān Manuscript (1st century AH) Hegira) in the undotted Hijazi script held in the Maktabat al-Jāmi‘ al-Kabīr, San‘ā’. The text starts from verse 13 of sūrat al-Zukhruf إِذَا اسْتَوَيْتُمْ عَلَيْهِ وَتَقُولُوا سُبْحَانَ الَّذِي سَخَّرَ لَنَا هَٰذَا وَمَا كُنَّا لَهُ مُقْرِنِينَ [then remember the favour of your Lord] when you are firmly seated thereon, and say: Glory be to Him Who made this subservient to us and we were not able to do it.

See Part One of this essay here