Recent research confirms that the Qur’ān was widely distributed among the Arabs because of the spread of churches, monasteries and monks who transmitted the Bible or Jewish and Christian works to the Arabs, and due to the spread of Christian heresies in the Arab regions. These heretics brought along their writings so as to spread their beliefs among the Arabs.

BY NAFI SHABOU

MUḤAMMAD REPEATEDLY STATED that ‘the book’ (the Qur’ān) is nothing but a confirmation of the previous books (the Torah and the Bible) to prove the sincerity of what was being communicated to them by the book that was in his hands, and to testify to them that his Arabic book was indeed a confirmation of the ‘foreign’ Hebrew book, which is the truth, and thus proved the truth of what was in his hands:

He has revealed to you the Book with truth, verifying that which is before it, and He revealed the Torah and the Gospel aforetime, a guidance for the people.[1]

Shaykh Khalīl ‘Abd al-Karīm in his book The Historical Roots of Islamic Law says the following:

Many [preachers] used to describe the period preceding the Muḥammadan mission with ugly epithets and described the Arabs of the island at that time using unpleasant terms, until it became broadly established in the mind that that era was nothing but a catalogue of obscurantism, ignorance and delusions, and that its inhabitants amounted to nothing more than a handful of dissolute, unthinking, uneducated barbarians with corrupt manners.

They were under the illusion that this served Islam, particularly since the Holy Qur’ān had described that period as the jāhiliyya [the ‘ignorance’].[2] But the opposite was the case; these preachers were actually insulting Islam since it would be absurd for the Qur’ān to have been addressing and disputing with people in such a state of ignorance. From reading the verses of dialogue it is clear that the interlocutors were fully capable of counter-argumentation and were capable of engaging in discussion. Otherwise what was the reason for the disputes and the disagreements, on questions that were frequently to be taken up by philosophers who spent their lives without succeeding in solving them: on resurrection, on creation, on the possibility of God communicating with people via miracles and so on.

Christoph Luxenberg observes that:

a quarter or a fifth of the Qur’ān contains obscure, meaningless or inexplicable words…. If we want to understand the Qur’ān correctly, we need to find a new interpretation and reading of it because the origin of the Qur’ān – that is, the first manuscripts of the Qur’ān – featured an Arabic in its infancy mixed with the ancient Syriac-Aramaic language,[3] and Muslim interpreters could not have been able to understand this mixed language unless they had knowledge of both Old Arabic and Old Syriac-Aramaic.

Elsewhere he adds that ‘the pointers to the Syriac Christian origin of the Qur’ān in Western encyclopaedias is something considered self-evident.’ The Qur’ān was initially not written entirely in Arabic but in a mixture of Arabic and Syriac, the spoken and written language prevalent in Arabia during the eighth century AD.

Pointers to the Syriac Christian origin of the Qur’ān in Western encyclopaedias is something considered self-evident

The German orientalist Gerd Puin, in his examination of the Ṣan‘ā’ manuscripts, states that:

my idea is that the Koran is a kind of cocktail of texts that were not all understood even at the time of Muhammad. Many of them may even be a hundred years older than Islam itself. Even within the Islamic traditions there is a huge body of contradictory information, including a significant Christian substrate; one can derive a whole Islamic anti-history from them if one wants.[4]

From all of the above, we can confirm the findings of researchers, Orientalists and specialists in archaeology, palaeography, inscriptions and coins about the nature of the Islamic sources in general and of the Qur’ān in particular. We discover that Islam is a combination of pre-Islamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Sabaean-Mandaean, in addition to Christian heterodoxy and heresy, non-canonical Jewish works, apocryphal Gospels, myths and oriental tales, in addition to pagan practices widespread in the East, and among the Arabs especially.

Suggested Reading

The most important sources from which the writer or writers of the Qur’ān drew to become ‘Qur’ānic’ texts, are the following:

Pre-Islamic pagan cults

- The worship of the deities of the Moon, the Sun and Venus and the sanctification and glorification of stones and idols

- The Aḥnāf or Ḥanafīs

- Arab soothsayers in the pre-Islamic era

- Poets of the pre-Islamic era

- Claimants to prophecy such as Musaylima ‘the Arch-liar’[5]

- Folk stories and tales of the ancients

- Sayings of the Companions (such as ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb) that became Qur’ānic verses

The Old Testament (the Torah)

Non-canonical Jewish writings such as the Babylonian Talmud and Midrash Rabba

The Isrā’īliyyāt[6] derived from folk tales, myths and legends

The New Testament, including the four Gospels, the Acts and Epistles of the Apostles and the Book of Revelation.

Heretical doctrines – sects that deviated from the Christianity of the Council of Nicaea 325 AD and not recognized by the main churches, along with heresies subsequently derived from these

- Gnosticism

- Judeo-Christianity

- The Ebionite heresy[7] and their apocryphal ‘Gospel according to the Hebrews’[8]

- Manichaeism

- Arianism

- Other miscellaneous heretical doctrines

Apocryphal Gospels,[9] such as:

Syriac prayers, legends and stories that have become Qur’ānic texts

The concept of resurrection and the Pharaonic Day of Judgment

Buddhism

The Sabaeans / Mandaeans

Zoroastrianism

Mazdakism

Other Miscellaneous Sources

In articles to follow, we will attempt to confirm all these sources.

[1] Qur’ān III (Āl ‘Imrān), 3.

[2] See, for instance: Qur’ān III, 154; V, 50; XXXIII, 33; XLVIII, 26. (Ed.)

[3] This script is term Karshuni (or Garshuni) which was Arabic using Syriac letters, a feature of the proto-literate stage of Arabic writings in the 7th century AD. Christoph Luxenberg attributes some mistranslations in the Qur’ān to this phenomenon, cf. Qur’ān CVIII (al-Kawthar), 2: فَصَلِّ لِرَبِّكَ وَانْحَرْ (‘So pray unto thy Lord, and sacrifice’) where وَانْحَرْ w-anḥar (‘and sacrifice’) is a misreading of the Karshuni Arabic text ܘܐܢܓܪ w-angar (representing the Arabic وانجر w-anjar). Luxenberg argues that the phrase was originally فَصَلِّ لِرَبِّكَ وانجر (‘So pray unto thy Lord, and persevere’). On this see, in the Almuslih Library, C. Luxenberg, The Syro-Aramaic reading of the Koran, pp. 292-300. (Ed.)

[4] Gerd R. Puin, Observations on the early Qur’an texts in San‘ā’ in Stefan Wild (ed.), The Qur’an as Text, Leiden, Netherlands, pp. 107–111.

[5] See footnote [2] in The Qur’ān according to critical research – 13. (Ed.)

[6] Isrā’īliyyāt (‘Israelisms’, ‘Judaisms’) refers to narratives assumed to have been taken into the hadith from earlier Jewish folklore. The term can also be extended to cover the genre of Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’ (‘Tales of the Prophets’). See Glossary: ‘Isrā’īliyyāt’ and the Almuslih article: The meaning of the term ‘Isra’iliyyat’. (Ed.)

[7] The Ebionites were considered by Greek Christians to be Jews who adhered to Jewish law but who also believed in Christ (in an anti-Trinitarian sense) and the virgin birth. Robert Kerr, in his work Islam, Arabs and the Hijra, argues that the Ebionites were a subsection of the Naṣārā and that this term is the source of the Arabic term Anṣār. The muhājirūn (‘migrants’) were thus Arabs while the Anṣār were Semitic anti-trinitarian Christians. See footnote [3] to Jadou Jibril’s Is the Qur’ān the work of Muslims? – 2. (Ed.)

[8] Note also the interesting case of the Elkesaites, and the claims of its founder to have received a revelation from heaven made up of ‘texts from every part of the Old Testament and the Gospels’, a ‘Day of Resurrection’ and a doctrine of taqiyya. See footnote [2] to Jadou Jibril’s Is the Qur’ān the work of Muslims? – 2. (Ed.)

[9] The compromising parallelism observed between texts in these apocryphal Gospels and the text of the Qur’ān is countered by Muslim scholars as constituting the ‘true texts’ that, conversely, the canonical Jewish and Christian scriptures have omitted due to their being corrupted. Philologians note, however, that the style and substance of the apocryphal Gospels is late and contradictory, while Muslim sources on the Prophet’s biography point to Muḥammad’s receiving these stories not from revelation via Jibrīl but from conversations with Christians. (Ed.)

[10] The Infancy Gospel of Thomas is a biographical gospel about the childhood of Jesus thought to be Gnostic in origin. It contains apocryphal stories of the child Jesus, such as the miracle of Jesus creating a bird from clay and his bringing it to life with his breath, which is repeated in Qur’ān III (Āl ‘Imrān), 49 and Qur’ān V (al-Mā’ida), 110. (Ed.)

[11] This Gospel also contains apocryphal stories of the childhood of Jesus, such as his miracle of making the palm tree drop fruit and a stream appear beneath it, which is reproduced in Qur’ān XIX (Maryam), 22-26, and the child Jesus speaking at the time from the cradle, referenced in Qur’ān XIX (Maryam), 29-31 and Qur’ān III (Āl ‘Imrān), 46. (Ed.)

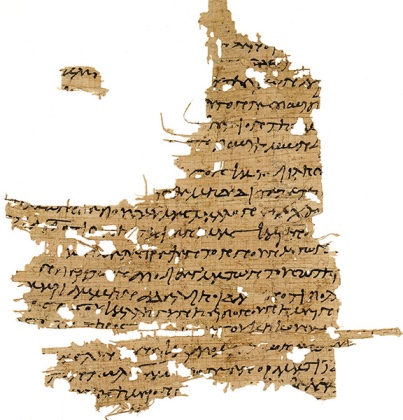

Main image: Papyrus fragment of the apocryphal Gospel of Mary

On this essay read the earlier sections: Part One; Part Two; Part Three; Part Four; Part Five, Part Six; Part Seven; Part Eight; Part Nine, Part Ten, Part Eleven, Part Twelve, Part Thirteen, Part Fourteen