Equality between human beings without distinction on the basis of sex, race or class is one of the core values of the Islamic religion, and the mosque as the place of worship is the first place to establish equality within its walls. Yet the gap between the divine discourse that dictates that all human beings are equal in value for being created from one and the same soul, and the popular jurisprudential discourse that degrades women, has led to the marginalization of the role of women.

BY MUNA ALI

WOMEN HAVE BEEN prevented from leading the prayer, issuing the adhān call to prayer or delivering sermons inside the mosque. Women have been suppressed within religious spaces in general. The principle bureaux of iftā (fatwā issuing bodies) have barred women from the office of muftī in any state and women are not allowed to express their opinions on major public issues such as those related to unofficial migration, bank interest or dialogue between religions and civilizations. The role of female scholars is limited to so-called ‘women’s jurisprudence’ and to dealing with issues related solely to women such as menstruation, or responding to enquiries from women only, rather than those of more general import.

For example, not a single woman has been admitted to the formation of the Council of Senior Scholars – the highest religious authority affiliated with Al-Azhar and a universal symbol of Islam – ever since its inception in 1911. Women have suffered from the dominance of male religious scholars in senior positions and decision-making positions within the religious institutions, and the absence of any fair representation means that the views and needs of women form no part of the decisions and fatwās issued by them.

The Qur’ān says nothing about prohibiting women from leading the prayer or preaching inside the mosque and issuing the call to prayer

Nowadays, in sermons and religious preaching councils we rarely hear accounts of women jurists such as Sayyida Nafīsa, despite her status as a core authority in the Sunna, one who was consulted by her leading contemporary jurists, including al-Shāfi‘ī, the founder of one of the four major schools of jurisprudence in the Sunni world, who requested that Sayyida Nafisa pray for him at his death. Then there is Sayyida Zaynab bint Muḥammad ibn ‘Uthmān who gave lectures on theology and hadith in the Abbasid era in Baghdad, and Sayyida ‘Ā’isha, about whom the Prophet said, “You should take half of your faith from this little rosy one”, and also Umm Waraqa al-Anṣāriyya who worked on collecting and memorizing the Qur’ān as well as on interpreting its meanings and who used to recite it in her own voice.

She was the woman whom the Prophet commanded to lead the prayer in her household and to whom he gave the sobriquet al-shahīda ‘the martyr’ even while she was still alive, since he foretold that she would die a martyr. But the male tyranny now opines that no woman has the right to be called a martyr, and fails to remember that the first martyr in Islam was Sumayya bint Khayyāṭ, and that Sayyid Khadīja was the first person to become a believer in Islam. But whenever the subject of rights is broached the sacrifices made by Muslim women are forgotten and erased, so that men may attain rank unchallenged.

Women’s rights in places of worship

The Qur’ān says nothing about prohibiting women from leading the prayer or preaching inside the mosque and issuing the call to prayer with their own voice provided they possess the conditions of a clear and sonorous voice. The Prophet allowed Umm Waraqa bint ‘Abd al-Allāh ibn al-Ḥārith al-Anṣārī to lead the prayer, and in the book Sunan Abī Dāwūd – considered a core work of hadith – it says of her:

She recited the Qur’an. She sought permission from the Prophet to have a muezzin in her house, and he gave her permission.

In the Musnad of Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, a leading hadith scholar of his time and one of the four great imams of the Sunnis, it states:

It is reported that Umm Waraqa bint ‘Abd al-Allāh ibn al-Ḥārith al-Anṣārī compiled the Qur’ān, that “the Prophet commanded her to lead the people of her house”, that she had a muezzin, and that she used to lead the people of her household in prayer.

Imam Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal permitted women to lead men in superorgatory prayers such as the Tarāwīḥ and Eidprayers, which are Sunna but not obligatory according to the consensus of jurists. Why then do not we see today a woman leading the Eid prayers or preaching to the worshipers both male and female?

Imam Abū Thawr, Imam al-Muznī and Imam al-Ṭabarī, who lived during the first three centuries of Islam, also permitted women to lead both the obligatory and supererogatory prayers on the basis of the hadith (a ṣaḥīḥhadith, moreover) that permitted Umm Waraqa to led the prayer, and because the Messenger allowed her to lead the obligatory prayers – as indicated by his granting her a muezzin – the adhān call being only prescribed for the obligatory prayers.

In part one of his Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya Ibn ‘Arabī states the following:

That a woman can lead the prayer is entirely correct and the default starting point is its permissibility. Whoever claims, without authoritative evidence, that this is to be prevented is not to be listened to for there is no text to prevent this.

Some base their objections on a weak hadith – narrated solely by Ibn Majah and not mentioned in other core authoritative works of hadith – that runs:

No woman should be appointed as Imam over a man, no Bedouin should be appointed as Imam over a Muhajir, no immoral person should be appointed as Imam over a (true) believer, unless that is forced upon him and he fears his sword or whip.[1]

But this contradicts the Messenger’s words:

The person who is best versed in the recitation of the Book of Allah, should lead the prayer[2]

in addition to lacking the principle of justice by limiting the Imamate to some Muslims over against others.

A constant anxiety in men and a sense of threat at losing their privileges

If the body of a woman issuing the prayer is the cause of fitna (‘social disruption’), as some such as al-Qaraḍāwī mention:

in that a man is to focus his thoughts on his prayer and his passion on establishing his bond with his Lord, so his mind should not wander beyond the circle of faith and there be nothing to rouse his human instincts,

– then it is more appropriate that these people evaluate to the basic sincerity of their prayers. If these are not preventing them from vice and obscenity, or from vulgar thoughts about women praying inside the holy spaces, what are they then thinking when women are present in all other spaces today? For women are today present everywhere and men are having to deal with women at work, on public transport and on the street.

Religious discourse treats women as a passive subject-matter, despite the fact that they are active and present everywhere and have been at all times

Denying the changing dynamic frameworks that govern gender relations in contemporary reality is no answer: men are the ones who have to change and evolve their views. Instead of denying women their rights in religious spaces such as leading the prayer, delivering sermons, issuing the adhān call for prayer, or assuming leadership positions within religious institutions, we must work to reshape social ideas that see it as the right of one gender to exclude the other, without taking into account the rights of that other to exist, to act and decide for itself.

Some imams mention that women are not suitable for preaching inside the mosque due to their ‘emotional nature’ and that they may be intimidated by a large crowd of people looking up at them. If so, why is this effect exclusive to the mosque and not seen in lecture halls in universities where women give lectures, or in school classrooms or at celebrations and large gatherings where women address thousands of people, or in women who win election contests for parliaments, union councils and elsewhere?

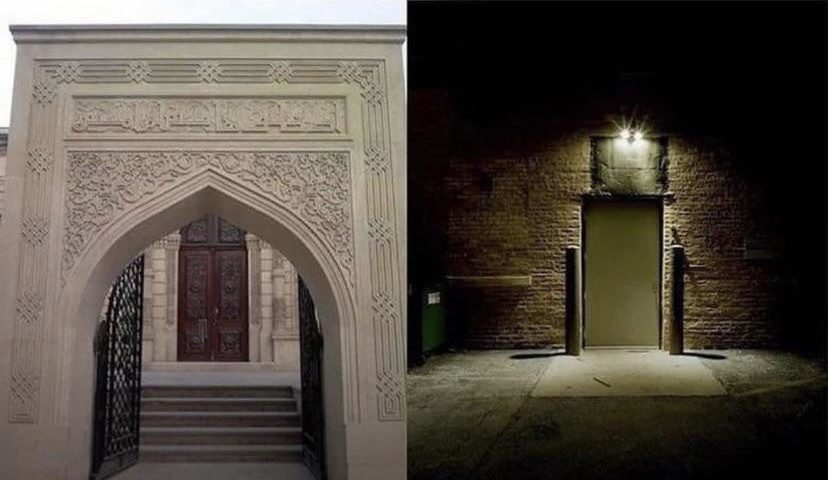

Special places of worship for women

In places of worship women now pray in what is called the ‘women’s muṣallā’ (‘oratory’), which are in fact cramped places to one side that are not lavished with the same level of extravagance spent on the men’s muṣallā’ nor given as much attention. In Egypt, for example, during the global Covid crisis mosques were closed to prevent the spread of infection and to preserve lives. After the seriousness of the crisis abated, men’s mosque areas were duly reopened, while women’s mosque areas were not and continued to be closed for a period of a year more or less. Moreover, the areas designated for women’s prayer are narrow and do not enable women to dialogue and interact with the imam or the preacher, since they are blocked off from the rest of the mosque.

It was not Allah but patriarchy that discriminated between the male and the female

In most cases, prayer rooms for women are located on a second floor, and the entry door is very narrow, as are the stairs. This prevents women with special needs, or the elderly, from performing prayers in the mosque. If there any emergency occurs it would be a major disaster – unlike the areas of worship designated for males, where the doors are wide and spacious, with their entrances located directly onto the street so that access or egress is easy.

Male domination of the religious institutional space

In contrast to the sacred religious text which considers all equal, there are wrong interpretations and applications of that text. As a result, over time the oppression has accumulated from the product of a thinking that sought to exclude and marginalize the experiences of women in the religious sphere and did not account for the integration of the female perspective in religious discourse or decision-making within the religious institutional structures. Since religious institutions have the highest authority to shape social and political discourses within our Arabic and Eastern societies, the impact of their marginalization of women goes beyond internal matters and reaches the lives of women in society in general.

Suggested Reading

Religious discourse treats women as a passive subject-matter, despite the fact that they are active and present everywhere and have been at all times. But the marginalization persists as does the insistence on treating women as submissive dependents, rather than active partners.

Permitting the right to participate in collective worship as it was at the beginning of Islam

It was not Allah but patriarchy that discriminated between the male and the female. The social balances that governed the past have changed, and women have become pioneers and workers in all fields. This requires that we take a new look at the human-based interpretations and jurisprudence that were relevant for the times in which they appeared. These interpretations emerged in the past from the interaction of jurists with their societies and due to needs that differ from the needs of our present-day societies.

The core values which Islam brought must continue to be what its adherents seek to apply at all times and places, so that Islam may continue to establish justice and equality for all. The mosque is the first starting place for equality, one where any dividing up according to male whims and interests is to be avoided. Altering this hierarchy to return women to the religious sphere is not some revolutionary event, but rather a course-correction and a return to the origins where, at the time of the Prophet, women and men prayed in one and the same mosque without any barriers or hierarchies.