In the book Al-Nabī al-Khātim by Shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan al-Nadawī – one of the poles of the Muslim Brotherhood and a leader of political Islam – he praised the role of some Orientalists in recognising the truthfulness and integrity of the Qur’ānic text from any distortion. He mentioned some of them by name, such as Sir William Muir, Edward Palmer, Stanley Lane-Poole, Alfonse Mingana and others.

HE THEN GOES ON to conclude on this basis that since the Holy Qur’ān is intact and has not been distorted, it must be truer in content than the Holy Bible, which has suffered distortion according to Muslim belief.

This attitude of al-Nadawī raises several questions: Why, then, are the shaykhs of Islamic groups and fundamentalists keen to describe Orientalists as infidels or conspirators against the Islamic faith? Why do they depict them with the ugliest reprehensible qualities they could find in the Arabic dictionary? Does al-Nadawī’s admission not betray a human conviction among fundamentalists that Orientalism is a scientific human phenomenon capable both of being right and being wrong?

Doesn’t al-Nadawī’s admission indicate that their constant attack on Orientalists is merely prejudice against another opinion or any critic in general? Doesn’t the revolt of groups against Orientalism indicate a rejection of alternative opinion altogether? And yet doesn’t the narrative which al-Nadawī maintained over two pages of his book, (pp.30 and 31), indicate that Orientalism is not a conspiracy but nothing other than an attempt by the West to learn about Islam?

When the context is one of da’wā for Islam they readily cite the views of Orientalists, but when the context is a defensive one they attack Orientalism

What al-Nadawī did was repeated in the writings of al-Qaraḍāwī and Muḥammad al-Ghazālī, where when the context is one of da‘wā for Islam they readily cite the views of fair-minded Orientalists, but when the context is a defensive one they attack Orientalism in general and paint all Orientalists with the traits of disbelief, conspiracy and devilishness. Such behaviour extends to the groups’ rejection of cultural pluralism except where their right to control and dominate the world by military force is conceded. Or where the necessity of rendering all peoples, religions and states subservient to the rule of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi current in general, is recognised.

At the same time that groups cry out about the racism of the West and the supremacism of the white man over other races, they adopt a similar belief – the idea of the superiority of the Sunnī Muslim, especially those whose opinion agrees with supremacy to other races and religions. For these have turned Islam into a race by declaring that the Islamic caliphate must be a farḍ kifāya – an obligation imposed upon the community – which requires that the caliph be an Arab from the tribe of Quraysh. This is the same idea that the internation Zionism held to, that the state of the Promised Land was to be ruled by a prince from the Children of Israel. It is the kind of policy that, once it becomes a matter of belief, is lent a dangerous military character that propagates terrorism and murder. It strips religion of its tolerance, its latitude and purity of soul towards God, in favour conflict, criminality and very long lines of the dead, the displaced and the threatened.

What they failed to understand was that the Orientalism that studied the Middle East, the Arabs and Muslims, also studied China, Japan and India. For instance, the German scholar Max Muller resolved the obscurities of the ancient Sanskrit language, yet we have not seen any in those cultures rushing to declare hostility against Orientalists in the way we are witnessing in our Arab region.

They confuse the phenomenon of Orientalism with colonialism, simply because their appearance on the stage of history occurred simultaneously

In the Arab and Islamic consciousness there is the phenomenon of a deep-rooted inferiority complex, one that assumes the superiority of Western nations, and assumed that it is only motivated by a sense of conspiracy against the Muslims. In the Arab and Islamic imagination the statements of the Orientalists are therefore always a blend of colonialism and conspiracy. This is what we learn, for example, from the writings of Muḥammad al-Ghazālī, Muḥammad ‘Amāra, Mālik Bennabī and ‘Abd al-Wahhāb al-Masīrī, where they confuse the phenomenon of Orientalism with colonialism, simply because their appearance on the stage of history occurred simultaneously in parallel. There therefore must be some natural, ‘logical’ link between the two phenomena.

In my opinion, this clear expression of rejection of Orientalism and blaming it for all the grievances and tragedies of Muslims, in the same way that colonialism is held responsible for these tragedies and the failure of officials, contains within it an invisible defense of the man-made doctrinal and religious ‘constants’ that the Orientalists have attacked. For the outside-of-the-box critiques that accompanied the methodologies of Orientalism not only touched on the origins and ‘constants’ of narrowly-defined doctrine, but also went to the heart of the faith itself and its universal certainties.

Orientalism touched on the ‘constants’ of narrowly-defined doctrine and went to the heart of the faith and its universal certainties

For theirs was a scientific phenomenon that can be said to have been a call to revive the Abbasid era when translators and philosophers were fully active and where there was an increased intellectual and religious awareness towards examining beliefs with a philosophical mentality, and not via a narrative text. This was an era that witnessed the emergence of many atheists and agnostics, and so the rise of Orientalism has reproduced once again the phenomena of atheism and agnosticism in Muslim society.

The origin of this fear among these groups is that they define themselves as ‘guardians of the faith’ and thus conceive of themselves as world leaders, as officials and observers of consciences. Any alternative opinion is therefore made to be some prelude towards violating this conscience and the responsibility that has been entrusted by God to them alone as opposed to the rest of humanity who are, of course, judged to be followers to them and subservient.

And since Orientalism was focusing on this aspect and promoting freedom of conscience and thought, it was only natural that it touched a raw nerve wound in the thinking of these groups, so that they viewed any opinion associated with the Orientalists as something dangerous in and of itself.

Suggested Reading

Orientalism as an epistemological necessity for enlightenment – 2

What escaped them was that the phenomenon of Orientalism in the 19th century was accompanied by scientific and industrial development, a modernity that posed questions in the human soul about how things are, about existence and about metaphysics, and so on. The biggest challenge faced by the Muslim shaykhs was the evolution in the human mind that was taking place through scientific discovery, precisely because such discovery was raising more questions than it cared to provide answers for.

They therefore chose to deal with the second part of this modernity: they considered that it was this modernity that was responsible for the conspiracy, the colonialism, and for scientific miracles. But they paid no attention to the nature of discovery itself – that it spawned creativity and scientific breakthrough even in an environment of ignorance. Consequently it straightaway imposed questions concerning its relationship with the universe, with existence and, of course, with religion.

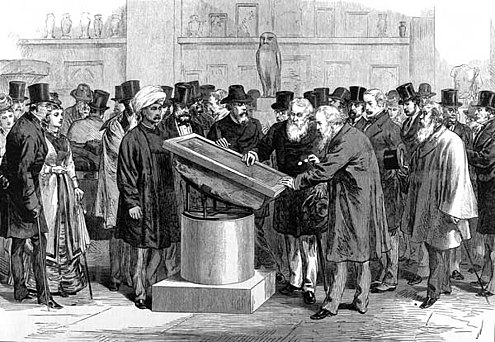

Main image: Scholars inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the Second International Congress of Orientalists in London, 1874.