Can clerics ‘renew’ the Islamist heritage? The answer is a categorical ‘no’, and to ask them to do so is like asking a wolf to guard the sheep. The more important question is: why can't they renew the religious heritage? And if not them, who can? What motivates them to want to renew, and what are obstacles preventing them from doing so?

WE SHOULD FIRST take a look at what ‘heritage’ is. In its simplest, technical definition heritage is the full record of human activity in a society over a long period of time. In other words, it is the totality of human activities that have been preserved in the collective memory of a people, and which is reflected in that people’s present, in their thinking and behaviour. This record of heritage may be expressed in a poem, or a historical document, a literary work, a scientific invention, a literary work, or a painting, a sculpture, a work of architecture, or in legendary tales, a popular saying, or a public festival, a family tradition, or a social custom.

This jurisprudential heritage has promoted the emergence of a folklore founded upon legends and myths

Heritage, in short, is an accumulated historical record of long and multifaceted human activities (cultural, literary, economic, social, political, architectural, and so on), which together makes up the identity and specificity of every society and which distinguishes it from other societies. We still find in Iraqi society traces of the Sumerian, Assyrian and Persian heritages. In Syrian society there are Canaanite and Phoenician traces, in Egyptian society there are Pharaonic and African landmarks, in North Africa there are Amazigh traces, along with Islamic and European landmarks. All of these are inherited from both the distant and recent past, and they express that people’s cultural identity.

The Islamists’ heritage

The Islamic heritage is a human gift fashioned by the Persians for their worst Arab enemies who were living in a harsh Bedouin environment and were characterised by savagery and criminality, devoid of any elements of culture and civilization. Since this synthesis took place, the heritage has relied on conflicting and accumulating religious rules, varying according to different times and places. It is a jurisprudential (scholastic) heritage, one which clashes with any heritage prior to it or following it and which the Islamised individual may, or may not, adhere to. It has led to the establishment of many acts or rituals that the individual Muslim may practice openly or covertly, or indeed may never practice in his life. In this sense, it causes a sharp schizophrenia in his personality. It also has no tangible heritage such as museums or ancient archaeological monuments, as is the case in neighbouring lands such as Iraq, Yemen, Egypt and others.

These unleashed explosive scientific, intellectual and cultural disputes concerning their internal contradictions and inhuman fallacies

It is basically formed from ideas derived from the verbal product of clerics, jurists, writers, thinkers and innovators, each in his time, and populates thousands of libraries in various countries and continents. This in addition to the sanctification of certain persons and places and some relatively recent architectural achievements. This jurisprudential heritage has promoted the emergence of a folklore founded upon the legends and myths contained in the former.

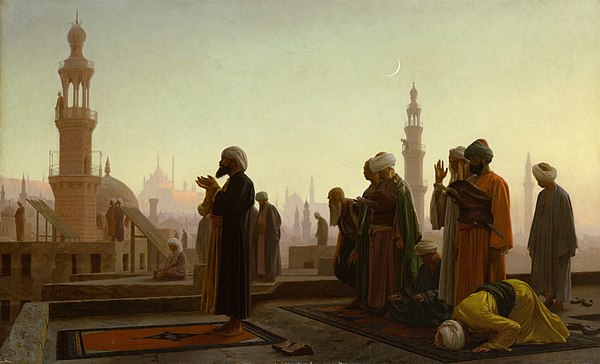

Islamic folklore is evident in social behaviour represented by customs and traditions prevailing in society and the extent of their sway over its members, their close relationship with cultural practices and their visions of the future, and the link between their present and their past. The meaning of religion for the public, strongly supported by the clergy, is limited to traditional ceremonies, popular customs, and the sanctification of individuals and venerated places, while at the same time linked emotionally to the events of the past. This has been a most effective means of consolidating the cultural identity of Islamized societies. In addition to the political ideology of religion, an overwhelming emotional ideology has emerged among those Islamised, one that is promoted and protected by institutions with influence over societies that are ignorant or made to be ignorant, societies that are subject to injustice, oppression, corruption and both material and moral decadence.

The essence of the Islamists’ faith has had no other purpose than to persistently seek political power, worldly hegemony, and an immoral Machiavellianism

This jurisprudential heritage from its very inception was built on hating non-Muslims and the enemies of the Islamists, upon an urge to despise them, assault them, loot their property and rape their women, and kill them with a clear conscience unshaken by the slightest sense of remorse, on the grounds that such was the indisputable command of the divinity. Islamists firmly believe that the Qur’ān and the ṣaḥīḥ Sunna of the Prophet constitute the main sources of the Islamic heritage, even though right from the beginning these unleashed explosive scientific, intellectual and cultural disputes concerning their internal contradictions and inhuman fallacies that often spilled over into fighting others and even engaging in internecine killing among the Islamists!

The essence of the Islamists’ faith is a complete doctrinal, emotional, and popular ideology steeped in politics which, from its beginnings until now, has had no other purpose than to persistently seek political power, worldly hegemony, and an immoral Machiavellianism. We have all seen how ISIS militants and other murderous, destructive groups cite so much of this heritage to justify their bloody acts. Hence, we do not find in this religion any other identity than that which manifests itself in these purposes, and which these groups have practised violence over history in order to achieve them.

Those that can accommodate, new knowledge and critiques into their heritage are better prepared to maintain continuity

The jurisprudential and popular Islamic heritage, like any other heritage made by man, is not something that should be sanctified in any way, even if it is claimed that a revelation unleashed it, since it is not a revelation but a human act, however much it is linked to an alleged revelation. It is therefore useful to study it and cleanse it of its disastrous impurities. Any culture that boldly critiques its own history and learns from the lessons of its heritage is capable of creatively shaping its future heritage, in a way that can keep pace with change without compromising on authenticity. Those that can accommodate discoveries, new knowledge and critiques into their heritage are better prepared to maintain continuity through change.

Despite a huge leap in the development of human thought globally, the Islamist heritage continues to stagnate, and we still find clerics attempting to strip the heritage of any responsibility for the corruption, decadence and backwardness suffered by Islamists today. We hear how the Shaykh of Al-Azhar in a conference convened by him in 2009 under the title The Renewal of Islamic Thought and Science, angrily demanded to “please look for the problem other than in the heritage!” It is as if the ‘renewal of Islamic thought and science’ is to take place in isolation from the critique of the heritage.

Suggested Reading

The Shaykh of Al-Azhar and those with him imagine that criticism of heritage represents some sort of malicious aggression or serious conspiracy against them. This is because they lack this dimension of criticism, and realize that the religious institutions in charge of protecting this heritage will collapse over their heads, if the criticism of the heritage makes any real inroads towards actual change.