Some measure of embarrassment occurs to some researchers when they delve into the poetry of Christian Arabs in the pre-Islamic era, because passages in many verses of the Holy Qur’ān are similar to some of this poetry, often textually identical. The researchers’ reluctance to access this approach is likely due to the fear that such approaches and comparisons made between Qur'anic and human sources could lead to the establishment of some facts.

BY NAFI SHABOU

FOR PIOUS FOLK, this reality might feel like an insult and a blasphemy. Some hardliners do not accept that the Holy Qur’ān is subject to historical research, or to have any source other than God directly. For these, the Qur’ān is entirely true to the ‘Preserved Tablet’.[i] However, God’s words are only effective if they are understood, and to be understandable they must be the same as the words of human beings. So why this fear of linking God’s words with those of mankind? Moreover, the Qur’ānic discourse actually confirms this point:

Say: Believe therein or believe not, lo! those who were given knowledge before it, when it is read unto them, fall down prostrate on their faces, adoring. [Qur’ān XVII (al-Isrā’) 107]

But those of them who are firm in knowledge and the believers believe in that which is revealed unto thee [Qur’ān IV (al-Nisā’), 162]

They looked upon this Arab nation as if it were a unique entity that knew nothing of others, and others knew nothing of it

Dr. Taha Hussein, a towering figure of Arabic literature, had this to say on the matter:

The researcher must get used to the lessons given by the history of ancient nations which were destined to achieve great things, and the difficulties and tribulations they lived through and the features of their discourse and behaviour, if he wishes to properly understand the history of the Arab nation and get to the roots of everything.

If there were things that those who wrote the history of the Arabs and their literature assumed was true, but did not correspond to the reality, that is because they did not know enough about the history of these ancient nations, or it did not occur to them to compare the Arab nation with the nations that preceded it and had since passed away. Instead, they looked upon this Arab nation as if it were a unique entity that knew nothing of others, and others knew nothing of it: no one resembled it in any way, it effected no one and was effected by no one, before such time as Arab civilisation was established and its sway was extended over the ancient world.

But the truth of the matter is that if they were to study the history of these ancient nations and compare it with the history of the Arabs, their views on the Arab nation would change, and thus the history of the Arabs themselves. I refer to but two of these ancient nations: the Greek nation and the Roman nation. [ii]

Here, the writer and doyen of Arabic literature, Taha Hussein, puts his finger on a fact that has long been hidden by the large part of Arab historians and scholars: the influence on Arab civilization of the historical roots of previous civilizations (including, of course, their previous religions) as the basis of any subsequent civilization. I would like to add to what Taha Hussein said, and that is, that Arab and Muslim researchers, religious scholars and historians, must focus on the pre-Islamic religions if they wish to understand and know Islam better than they know it and understand it today.

Scholars and historians must focus on the pre-Islamic religions if they wish to understand and know Islam better than they know it today

Taha Hussain goes on to add:

It is not easy, not to say impossible, to believe that the Qur’ān was completely new to the Arabs. If it were, they would not have understood it or been aware of it, some would not have believed it or opposed it and argued with it as well.

Elsewhere in the same work he says:

Any reading of the Qur’ān in depth shows us that a large part of its verses were revealed according to the Islamic view on controversy, strife and dialogue in religion…The people who were arguing and dialoguing and quarreling with Muḥammad were not ignorant, stupid or course folk, but possessors of knowledge and intelligence and capable of finer feelings and living a life of grace and tenderness.[iii]

The scholar Boulos Feghali notes that:

When we read the Bible, beginning with the Old Testament, we ask ourselves: What is the Bible? We say that it is an essential book in the life of the believer, a book like no other. From this book was born Judaism, Christianity rooted itself in it, and the Islamic world drew from it many of its texts. So, when we read the Bible we are going back to our roots, we are returning to the foundations of a civilization that is part of our own. The Bible is where our origins and history lie. Therefore if we want to understand the faith trajectory of our ancestors, we must not forget their long history and their voyage in the journey of faith, an example of which is Abraham.

That is, we have to return to our original roots to grasp what we are today. The above view is supported by the writer Mūsā al-Ḥarīrī, who says the following:

We cannot understand any of the teachings of the Qur’ān if we overlook the teachings of the Gospel of the Hebrews (an apocryphal book that was circulating among the Christianized Jews) which the priest Waraqa ibn Nawfal was intending to translate from Hebrew to Arabic. Nor can we understand the stories of the ancient prophets, or the teachings of the Torah and the Gospels contained in the Qur’ān, if we do not go back to their origins.[iv]

We might wonder in turn whether Islam arose without any significant impact from the two monotheistic religions that pre-dated its emergence. What is the relationship between Christianity and Islam and the relationship of the Qur’ān to the Bible and other books? Why do Muslim Arabs not accept critical research or the historicity of Qur’ānic texts or accept any comparative study of pre-Islamic religions of the Book? Where do the historical roots of the Arabs lie before Islam? Why do they cut themselves off from their Christian roots and avoid mentioning them whenever they focus on the pre-Islamic era when the Arabs worshipped idols, with the facts thus distorted, since there were more than 45 Arab Christian tribes?[v]

Why do Muslim Arabs not accept critical research or the historicity of Qur’ānic texts or accept any comparative study of pre-Islamic religions of the Book?

These are valid questions which the everyday Muslim needs to get answers to from Muslim religious shaykhs and scholars, especially since we know via Ibn Hishām’s Al-Sīra al-Ḥalabiyya that Waraqa bin Nawfal had asked the Messenger of Islam:

What is it that you see? – referring to what he saw during the process of revelation – and the Prophet told him what he saw. “This is the nāmūs that was revealed to Moses” replied Waraqa bin Nawfal. [vi]

That is, what was revealed to the Messenger was already found in the Old Testament (Torah) written by Moses.

See also the following Qur’ānic verses where it affirms that the Bible is to be recognized in its two covenants:

O Children of Israel! Remember My favour wherewith I favoured you, and fulfil your (part of the) covenant, I shall fulfil My (part of the) covenant, and fear Me.

And believe in that which I reveal, confirming that which ye possess already (of the Scripture), and be not first to disbelieve therein, and part not with My revelations for a trifling price, and keep your duty unto Me. [Qur’ān II (al-Baqara), 40-41]

How come they unto thee for judgment when they have the Torah, wherein Allah hath delivered judgment (for them)? Yet even after that they turn away. Such (folk) are not believers.

Lo! We did reveal the Torah, wherein is guidance and a light, by which the prophets who surrendered (unto Allah) judged the Jews, and the rabbis and the priests (judged) by such of Allah’s Scripture as they were bidden to observe, and thereunto were they witnesses. So fear not mankind, but fear Me. And My revelations for a little gain. Whoso judgeth not by that which Allah hath revealed: such are disbelievers. [Qur’ān V (al-Mā’ida), 43-44]

One writer notes the following:

It seems that the relationship between Islam and the earlier revelation was never the subject of the study for the early Muslims, and I do not know the reason for this. One may naturally ask that if the Qur’ān did not abrogate the commands of the Torah and the Bible, were these commands therefore still binding on the Muslims?

Many Muslim religious shaykhs and scholars classify the Jews and Christians as infidels and polytheists and they forget, or pretend to forget, their Christian roots. When a people is cut off from its historical roots, it is a dead people, much like a tree that is severed from its roots. This is what sociologists and psychologists tell us.

Suggested Reading

Believing in a revealed book without granting freedom to research for the truth is a form of fanaticism striking against human dignity and freedom. God does not take away man’s freedom but leaves him free to contemplate his history. A specialist in Islamic affairs notes that:

The majority of the areas occupied by Muslims in the West were Christian, even those areas from which Islam emerged.

Judaism and Christianity were thus not contingent on the view of the Islamic religion, but according to Qur’ānic texts (more than 117 verses) already existed, and there is indisputable evidence of their having influenced the Islamic faith.

[i] The doctrine of The Preserved Tablet (al-Lūḥ al-Maḥfūẓ) takes its origin from texts such as Qur’ān LXXXV (al-Burūj) 21-22: بَلْ هُوَ قُرْآنٌ مَجِيدٌ فِي لَوْحٍ مَحْفُوظٍ (‘Nay, but it is a glorious Qur’an on a guarded tablet’) and Qur’ān XLIII (al-Zukhruf), 4: وَإِنَّهُ فِي أُمِّ الْكِتَابِ لَدَيْنَا لَعَلِيٌّ حَكِيم (‘And verily it is in the original of the Book with Us, truly elevated, full of wisdom’). (Ed.)

[ii] Taha Hussein, في الأدب الجاهلي Chapter 3.

[iii] Taha Hussein, في الشعر الجاهلي, p.382.

[iv] Abū Mūsā al-Ḥarīrī, القص والنبي، بحث في نشأة الإسلام, Beirut, 2005. For this work see the Almuslih Library here.

[v] See the work by Louis Cheikho: Religions in the Arabian Peninsula which details how Christianity was widespread throughout the Fertile Crescent and the Arabian Peninsula, and even in the Hijaz. See also his work النصرانية وآدابها بين عرب الجاهلية (‘Christianity and its Literature among the Pre-Islamic Arabs‘) in the Almuslih Library.

[vi] Ibn Hishām, Al-Sīra al-Ḥalabiyya, Vol. 1 p.25. See also Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3: فَقَالَ لَهُ وَرَقَةُ هَذَا النَّامُوسُ الَّذِي نَزَّلَ اللَّهُ عَلَى مُوسَى Waraqa said, “This is the nāmūs that Allah sent to Moses”. The word nāmūs in this passage is customarily translated as ‘the angel’, denoting Jibrīl, but is actually the Greek word νόμος, meaning ‘law’ mediated through Syriac to mean ‘the revealed law’. See also Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3392. The fact that the Waraqa story came to be prefaced with narrations about visions of the angel Gabriel, contributed to the development of the idea that al-nāmūs referred to the angel Jibrīl. On this, see in the Almuslih Library the Encyclopedia of the Qur’ān Vol. 3, p.515: ‘Nāmūs’. (Ed.)

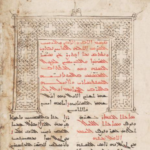

Main image: The martyrdom of the Arab Christian Arethas (al-Ḥārith) in Najran, from the 11th century Byzantine Menologion of Basil II.

See Part One of this essay here