Although the Hijri calendar dates itself from the migration of the Prophet Muḥammad from Makka to Madina, it did not come into force until 17 years after the actual hijra (‘migration’). It is said that the Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb was the first to adopt the hijrī calendar for the Islamic state, and that it was previously known as the ‘calendar of the Arabs’. It only acquired the word hijrī after it became linked to the Prophet’s migration. The names of the months which we know today were chosen after the tribes had given different names to the months. These are for the most part the names agreed upon by the Arabs at the Makka meeting in 412 AD.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

THE NAMES OF THE MONTHS were associated either with the seasons that coincided with them, the activities of the Arabs in each of them, or the prohibition of fighting in them. For example, the months of Rabī‘ al-Awwal and Rabī‘ al-Ākhir corresponded to the spring season when they were named. Jumāda al-’Ūlā and Jumāda al-Ākhira coincided with winter when they were named (the word jumāda itself deriving from stagnation of water). The month of Ramaḍān derives from the word ramūḍ, which denotes the intensification of heat at the time it was named. As for the sacred months, Dhū ’l-Qa‘da symbolizes the Arabs’ holding back from warfare, while al-Muḥarram is derived from the prohibition of fighting. Dhū ’l–Ḥijja was the month of ḥajj, and Rajab derives from rajab al-naṣāl ‘an al-sihām, ‘honouring the renouncing of arrows’, i.e. removing their usage at the time when fighting is prohibited. As for Ṣafar, it was associated with the Arabs going out to war until the houses turned yellow, that is, when they became empty of inhabitants. Sha‘bān symbolizes the beginning of the Arabs dividing themselves up between war and trade after their holding back in Rajab.

Before the abolition of the nasī’ the month of Ramaḍān, the month of fasting, coincided with the Jewish month of Eylūl (September), where they would fast at that time of the year because it coincided with the period of Moses’ presence on Mount Sinai, as stated in the Old Testament. This month of fasting coincided with the summer when the Prophet Muḥammad arrived in Madina in 622 AD, and the abolition of the nasī’ coincided with the Farewell Pilgrimage.

Was the nasī’abolished to distinguish Muslims from Jews in their fasting?

Was the nasī’ abolished to distinguish Muslims from Jews in their fasting, given that the month of Ramaḍān was wandering through the seasons of the year and was not to fall in September for a long time? Does this mean that the early Muslims used to make the ḥajj outside the time of the Ḥajj and perform the fast of Ramaḍān outside its time, so that matters would not return to normal until the tenth year of the hijra, or was it vice versa? Alternatively, was it a case of seeking to detach themselves from what prevailed before the Muḥammadan call, and from earlier doctrines which Islam swept away?

With respect to the ḥajj, for example, ever since the Farewell Pilgrimage Muslims to the present day have only partially been observing its rituals. With the adjustments decreed by the Prophet, the rituals differ from what the pre-Islamic Arabs used to perform in their pilgrimage. By abolishing the nasī’ and adopting the unmodified lunar year, the Prophet removed from the Islamic pilgrimage everything that related to the solar pilgrimage. Details of these amendments were featured in the Sūrat at-Tawba.

The abolition of the nasī’

The nasī’ was abolished by the revelation of the Sūrat at-Tawba verse 37:

Postponement (of a sacred month) is only an excess of disbelief whereby those who disbelieve are misled; they allow it one year and forbid it (another) year, that they may make up the number of the months which Allah hath hallowed, so that they allow that which Allah hath forbidden. The evil of their deeds is made fair-seeming unto them. Allah guideth not the disbelieving folk.

In the Islamic narrative the reasons for this abolition were given as the following:

– The Arabs of the pre-Islamic era invented the nasī’ and gave it the status of God’s law and religion;

– Religion had been turned upside down, in that they had made that which was permissible forbidden, and that which was forbidden permissible;

– They were employing deception and trickery in God’s religion;

– According to the commentators, the nasī’ is nothing but an increase in disbelief.

Theories on the subject outside the Islamic system

The first Ramaḍān in Madina occurred in springtime and coincided with March and April 623 AD. In their disputes with Muḥammad the Jews asserted that fasting was for the month of Eylūl (September), and the month of Ramaḍān for the Arabs coincided with this month because they were employing the nasī’ to agree with the solar year. At that time the timing was established and did not change.

Some scholars have argued that, contrary to the understanding that the problem of the nasī’ was something between Muḥammad and the polytheists of Arabia, it was actually the subject of controversy between the Prophet and the Jews.

According to Jacqueline Chabbi, a French scholar specialising in medieval Islam, the abolition of the nasī’ in the late Madina era was made in order to pull the rug from under the feet of the Bedouin tribes with respect to their control over the issue of the prohbited period for warfare (the holy period), and was a statement of the Prophet Muḥammad’s supreme influence (politically and militarily) over the western Arabian Peninsula. According to the researcher, this was because it was the nomadic Arab tribes who were in control of the nasī’ and not the urbanised circles in the peninsula. The former were therefore the ones controlling the timing of the Autumn pilgrimage, the rituals for which were conducted outside Mecca and not in the Ka‘ba.

The hijrī year is none other than the Arabic linguistic equivalent of the ‘Year of the Arabs’ or the ‘Year of the Hājariyyūn’

Following the abolition of the nasī’, the Spring Pilgrimage in the vicinity of Makka and the Autumn Pilgrimage outside the Ka‘ba and Mecca were unified, and a single time was set for their observance. Before the abolition took place, in order to distinguish the Spring Pilgrimage and the Autumn Pilgrimage one should remember that Mina and Mount Arafat were located outside Makka. They were not part of Makka but were under the influence of the A‘rāb, the nomadic tribes surrounding Makka.

Jacqueline Chabbi argues that the decision to unify the two pilgrimages was made at the end of the Madinan era when political control over both the urbanised Arab and nomadic Arab spheres had been fully achieved.

Regarding the hijrī calendar, Robert Kerr, a specialist in Semitic languages and literature and Director of the Institute for Research in the History of the Origins of Islam and the Qur’ān (Inarah), has a particular view. His interpretation runs contrary to the Islamic narrative, since he denies that the Islamic calendar was associated at all with the migration to Madina. He starts from the original connotation of the verb hajara which does not mean ‘moving from one place to another’, but is taken from the Syriac word mahgraye, which means ‘Arabs’. So ‘the year of the hijra’ for him means ‘the year or annual reckoning of the Arabs’ adopted when the Arab clients of Heraclius defeated the Sassanids and subsequently obtained for themselves a great deal of autonomy, starting from the year 622 CE, the year of that battle.

Suggested Reading

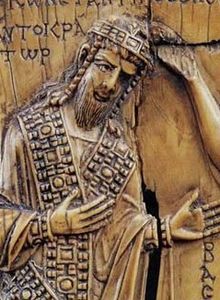

Thus Robert Kerr believes that the hijrī year is none other than the Arabic linguistic equivalent of the ‘Year of the Arabs’ or the ‘Year of the Hājariyyūn’. It was later reinterpreted to mean the ‘Year of the migration’. He believes that this event was not associated with an emigration (an escape), but was associated rather with a major event, a decisive victory in a great battle. Kerr supports his thesis by the fact that contemporary Christian sources on the origin of Islam do not employ the term ‘Muslims’ and rarely speak of Arabs. The term they used was Hagarites or Ishmaelites. He adds that the oldest evidence found that bears the term ‘Muslim’ is found in the Emperor’s Ἔκθεσις τῆς βασιλείου τάξεως (‘The Explanation of the Order of the Palace’) a manual of ceremony for the Byzantine court authored or commissioned by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus between 956-959 AD, more than three centuries after the beginning of the Muḥammadan call.

See Part One of this essay here