The present theme presents models and case studies that shed light on the approaches, mechanisms and methods of the slippery apologetic, reverential mentality, as it seeks to overcome embarrassment and hide blatant contradictions plaguing the heritage, its narrative and the early history of Islam.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

THIS SLIPPERY REVERENTIAL, justificatory mentality has been obsessed with searching for ways out of embarrassing dilemmas – a process that has made it, in the end, a mercurial way of thinking. In the opinion of many, the early history of Islam was dominated by beliefs and ideas that derived from myth and legend and an unquenchable desire to justify and revere at all costs and by any means. Such a history has at times become mysterious and piled up uncertainty over uncertainty over the centuries.

This mentality has sometimes produced strange results, some of them seeking to justify rhetorical or grammatical errors and the like contained in the Qur’ān. It also sought to nullify or leap-frog over some blatant contradictions contained in the hadiths – even the ṣaḥiḥ hadiths.

It has prevented researchers from breaking free of the inherited Islamic tradition, especially the problematic heritage of commentators and fuqahā’. The cognitive development witnessed by humanity and its tearing the veil from what had been hidden from the early history of Islam requires, today more than ever, that we do not place our reliance on much of the Islamic tradition that has come down to us, a tradition established mainly upon uncritical acceptance and lack of any calling to account.

This mentality has produced strange results, some seeking to justify grammatical errors in the Qur’ān

The case of Sūrat Maryam, verses 18-38

Lo! I seek refuge in the Beneficent One from thee, if thou art Allah-fearing.

This formula raises some questions, such as how to ‘seek refuge’ in the Beneficent One from one who is piously Allah-fearing, given that it is understood that one seeks refuge in God from Satan or those who are wicked.

The commentators were greatly embarrassed and tried to justify this strange formula, since one would assume that the formula should be in the negative, so that the meaning would take the form of something like I seek refuge in the Most Merciful from you if you are not Allah-fearing. Because seeking refuge in God is basically asking Him for help to avert danger or evil. For example, this is how it is phrased in Sūrat Āl-‘Imrān verse 36:

Lo! I crave Thy protection for her and for her offspring from Satan the outcast.

This flatly contradicts the justification of the commentators when they say that, ‘Seeking refuge is only effective through piety.’

This explanation shows itself up, given that Mary had cut herself off from people in order to worship God. How was it, then, that she knew that this impious person was Mr. ‘Allah-fearing’? They said that Jibrīl had reincarnated himself in the form and appearance of ‘Allah-fearing’, but why would the angel reincarnate himself in the form of this immoral person and not others? Also, this ‘explanation’ cannot easily march in step with the general context. If it is true that this is just an ‘explanation’, how should we deal with those who proposed this? Can one possibly believe the rest of their statements on other subjects? Can their writings be taken as an authoritative reference?

In fact, Sūrat Maryam, verses 18-38 place the commentators and jurists in a state of confusion and multiple embarrassment additional to the problem of ‘seeking refuge’ mentioned above, for it which prompted the mercurial, apologetic mentality to come up with ‘personal’ fabrications to avoid this embarrassment. It was claimed that there was at that time some licentious person named Taqī (‘Allah-fearing’) who was notorious for harassing and assaulting women, and that Mary had thought that it was him, and so she sought refuge’ in God from this ‘Allah-fearing’. This is an overtly tendentious ’explanation’, and points to a mere fabrication.

This is an overtly tendentious ’explanation’, and points to a mere fabrication

There are other problems with the above-mentioned verses, such as the place where Mary was when the event took place – the miḥrāb – which is a place of worship, the Holy of Holies where and the presence of a female was stringtly contrary to Jewish law. It is well known that for the Jews no one other than the High Priest is allowed to enter into the Holy of Holies.

These verses feature another obscurity, since in the Qur’ān that we have today it is stated:

He said: I am only a messenger of your Lord: That I will give you a pure boy.

Understood in this phrasing is that the giver is the angel – that is, that God sent him to give Mary a boy. So is the giver God or the angel?

Suggested Reading

The phrase ‘to give you’ ( لِأَهَبَ لَكِ ) appears in the San‘ā’ manuscript – which is the oldest manuscript of the Qur’ān that we have according to the consensus of palaeography scholars – without any diacritic dots and vowels, and was written as follows lām – )*) – hā’ – (*). The first (*) may be the letter ‘n’ and the second (*) the letter ‘b’, giving the sense ‘that we will give you’, so the giver is two givers: Allah and the angel. This is how Abū ‘Amr read it. Or the reading may be ‘that He may give you’, in which case the giver is Allah – and this is how Ibn Mas‘ūd and others read it. It may be that the first (*) was voiced as a hamza (‘glottal stop’), given that the hamza was written with a (*) in the absence of a diacritic mark, and the absence of a point on which the hamza could sit, as is the case today. It could therefore also be read ‘That I will give you’.

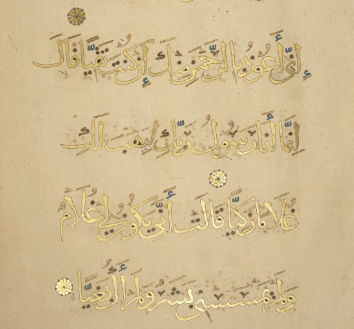

Main image: Sūrat Maryam, verses 18-20: قَالَتْ إِنِّي أَعُوذُ بِالرَّحْمَٰنِ مِنْكَ إِنْ كُنْتَ تَقِيًّا {18} قَالَ إِنَّمَا أَنَا رَسُولُ رَبِّكِ لِأَهَبَ لَكِ غُلَامًا زَكِيًّا {19} قَالَتْ أَنَّىٰ يَكُونُ لِي غُلَامٌ وَلَمْ يَمْسَسْنِي بَشَرٌ وَلَمْ أَكُ بَغِيًّا She said: Lo! I seek refuge in the Beneficent One from thee, if thou art Allah-fearing. He said: I am only a messenger of your Lord: That I will give you a pure boy. She said: How can I have a son when no mortal hath touched me, neither have I been unchaste? Illustration from volume four of a seven-volume Qur’ān commissioned by Rukn al-Dīn Baybars, later Sultan Baybars II, British Library Add MS 22412, folio 91v.