We said earlier that Josef Van Ess’s intellectual-historical encyclopedia was published in six parts between 1991-1997. Claude Gilliot, a French orientalist well versed in Islamic studies and author of significant writings and research made a study of this work entitled A Masterly Lesson in Orientalism: The Magnum Opus of Joseph Van Ess.[1]

BY HASHEM SALEH

FROM THE OUTSET, Claude Gilliot gets straight to the point: Some are complaining about the deteriorating situation of Oriental studies in the field of Arab-Islamic studies. They focus in particular on the methodological shortcomings of Orientalism. Others condemn what they call the negative Western view towards Arabs and Muslims in general.

On the other hand, Islamic circles blame the Orientalists for ‘distorting or disfiguring Islam’. It is claimed that they do not present it in a proper way or in its true form. Gilliot believes that this last accusation is unacceptable from a scientific point of view, and he is right. Why?

The fact is, conservative Muslims, not to say fundamentalists, reject any talk about Islam that is not reverential, sanctifying as opposed to historical. This is something that any self-respecting scientific researcher would never accept. As for the second criticism, made in the manner of Edward Said, this is also unacceptable because it is ideologically demagogic and wastes our time with sterile polemical arguments. Only one first criticism, made by Mohammed Arkoun is worth pausing over, and attracts Claude Gilliot’s attention.

Criticism, made in the manner of Edward Said, is unacceptable because it is ideologically demagogic

Arkoun clearly directs his criticism to Joseph Van Ess himself, despite his great respect for him and for his achievements. Indeed he also directs criticism to his friend Bernard Lewis and all exponents of classical Orientalism in general. And here we enter into the crux of the epistemological battle over Orientalism – not the ideological battle after the manner of Edward Said and the rest of Arab intellectuals. Arkoun criticizes Orientalism from an epistemological, not an ideological, point of view. but he does not criticize it without first acknowledging the greatness of its achievements and the extent of the services it has provided the Arab Islamic heritage. Here, his position differs on the one hand from the position of ideological Arab intellectuals and on the other hand from the position of the venerable fundamentalists.

How does Gilliot respond to the criticisms made by Arkoun that Orientalism has become outdated, insufficient, and even lags behind the course of contemporary scientific research in the West itself? Gilliot admits that one must inevitably renew Orientalist methodology in order to keep pace with the epistemological and methodological developments that have touched other, non-Orientalist, fields such as Biblical criticism, religious anthropology, literary criticism, linguistic, semiotic and semantic sciences and so on. These are fields in which Arkoun himself excelled in, applying it to Sūrat al-Fātiḥa (the ‘opening sūra’ of the Qur’ān) and indeed to the entire Qur’ān.

All this is necessary, says Gilliot, because no science can survive closed in on itself. Orientalism should accordingly open up to what is around it in terms of methodology and epistemology. It should be open to the humanities, especially the science of modern history in the manner of the famous French Annales School.[2] But he gives this warning:

“Applying the latest research methods to Arab-Islamic studies has its risks. The first is that the Islamic heritage, in contrast to the Western Christian heritage, has not yet been sufficiently explored from a classical philological and historical point of view. There are still many manuscripts that have not yet been investigated and have not been dusted off! Let us therefore complete the philological investigation of all the manuscripts of the Arab-Islamic heritage, and then we can apply these modern approaches to it. This means that Arkoun should wait a little and not intensify his open campaign against Orientalism and its old, outdated methodology!”

We note that Claude Gilliot does not specifically mention Arkoun’s name. Perhaps this was due to his respect for him and his unwillingness to confront him directly In fact, Arkoun’s viewpoint and Gilliot’s viewpoint are complementary, not necessarily contradictory. Gilliot acknowledges that Joseph van Ess operates according to the cautious, painstaking methodology of Orientalism, and does not uncritically introduce into the field of Orientalism the terminology and methods of other sciences. His methodological position may be summarized as follows: if scientific research is to advance in the Arab-Islamic field, particularly in the field of theology, the largest possible number of traditional texts should be collected. These should then be understood philologically – that is, linguistically – before being interpreted critically and historically. For as long as this basic work has not been done sufficiently, many people will continued to write generalised works on Islam which will not offer anything new for specialists in the cultural heritage.

Some aspects of the Joseph van Ess project

We understand from the general introduction to his major encyclopedia that Van Ess talks about Muslim scholars of kalām, that is, what in Christianity are called religious theologians. Kalām in Islam equates to theology in Christianity. The kalām scholars at the time enjoyed two privileges: the first was that they stood at the beginning, at the vanguard, so the path before them was therefore open. The second is that the society in which they lived had recourse frequently to theological discussions in order to explain its fate and destiny. We are here at the beginnings of Islam, not at its middle stages or where it ended up.

The fundamentalist Muslim is deluded if he thinks that Islam has always been like it is from time immemorial

Now the reader should not lose sight of this point. The kalām scholars were fortunate in that they were the conquerors and thus were not bound by previous rules and constraints. They were pioneers inaugurating a new science in which no one had preceded them. This situation was never be repeated. In addition, the Muslim community was ready to listen closely to what they had to say. This was fortunate too. For this reason, they stood not only at the center of daily life, but also at the center of major and decisive policy innovations and decisions.

It is for this reason that Josef van Ess spoke in this work of caliphs as well as of heretics, of wages as well as of sex. This means that the word theology is used here in a broad, or even the broadest, sense of the word. It indicates a discourse that speaks of reality with a religious tint, and one that received its orientations from a revelation that was still young and recent.

Professor Joseph van Ess admits that it would be difficult to grasp fully the two poles of this relationship between theology and society. Why is this so? It is because at that time the society, as much as the theology, were things that were still new and in search of identity. A study of the reciprocal or interactive relationship between them is at the same time an exploration of how Islamic ‘orthodoxy’ came to be born and how it formed.

Suggested Reading

Here Van Ess alerts us to the following highly important fact: that the fundamentalist Muslim is deluded if he thinks that Islam has always been like it is from time immemorial, in the sense that it has not undergone any change from its beginnings to now. It is a deceptive illusion, and one that indicates the atrophy, if not complete absence, of a historical sense among contemporary Muslims. The fact is that such a process of trial and error is experienced by every religion at its beginnings, and is not something confined to Islam, even if in Islam it took place in a highly complex manner.

The reason for this is that Islam’s adherents were scattered over vast areas. Thanks to wars of conquest they settled in the ancient world as a dominant class standing over the conquered peoples’ ancient classes. Regional developments thus took place separately from each other and were only unified latterly as a common Islamic consciousness formed. It is for this reason that we have to study this process separately in each region or city, in the Hijaz, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Kufa, Basra and so on. And this very process is what Josef van Ess actually pursued in his work.

[1] Claude Gilliot: ‘Une leçon magistrale d’Orientalisme: L’Opus Magnum de J. Van Ess’, Arabica. Tome, XL, 1993.

[2] The ‘Annales school’ refers to a group of historians associated with a style of historiography developed by French historians in the 20th century to stress long-term social history, using social scientific methods and emphasizing social and economic rather than political or diplomatic themes.

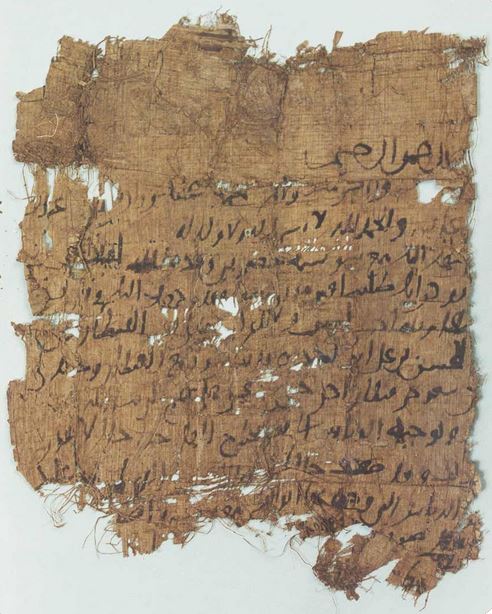

Main image: An Islamic papyrus manuscript from Egypt c.800 AD.