5 - The Qur’ān does not stand outside of history

If we exclude the jurisprudence of Aḥmad al-Qabbanjī and ‘Abd al-Karīm Soroush, and before them (to some extent ) Maʽrūf al-Ruṣāfī , then everything that has been said about the Holy Qur’ān since the death of the Messenger right up to the present day has not deviated from the foundational assumptions in the discourse of the ancients, or indeed from a magical view of the world, in which the Qur’ān appears as the ‘word, language, and style’ of Almighty God.

BY SAID NACHID

SUCH A SPEECH has therefore to exist as a result of one of three conditions: either it is written in the Preserved Tablet[1] (according to the jurisprudential discourse), or it was formulated by God in newly forming circumstances (according to the verbal discourse), or it is an emanation – in terms of its expression and its content – from the divine being (according to the ṣufistic and philosophical discourses). However, the Qur’ān, in any of its conditions, remains the ‘word, language and style’ of God, with all the meaning that this implies (according to everyone).

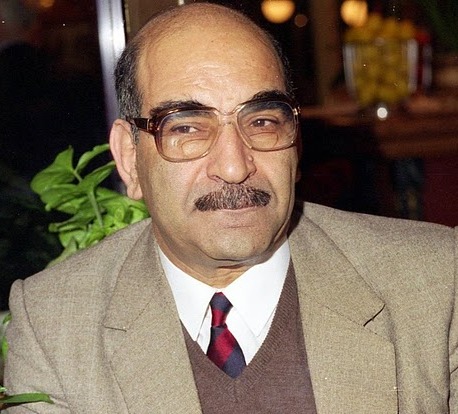

It is the same ancient paradigm that prompted both Muḥammad Shahrour and Muḥammad ʽĀbid al-Jabrī to accept that the Holy Qur’ān is not a constituent of the heritage. This is a major error.

In the introduction to his work The Book and the Qur’ān Muḥammad Shahrour emphasized that:

the book (meaning the Qur’ān) is not to be considered part of the heritage, for the heritage constitutes the relative understanding of people in a particular era [2].

It is the same assertion that al-Jabrī made in the first part of his Introduction to the Noble Qur’ān when he stated:

We have repeatedly stressed that we do not consider the Qur’ān to be part of the heritage. This is something that we re-affirm here, and at the same time we also confirm what we said on previous occasions: that we consider all kinds of conceptions that Muslim scholars have constructed for themselves around the Qur’ān… are all a matter of heritage [3].

Thus, whereas Shahrour and al-Jabrī deal with the issue as one of the postulates of handed down records, we cannot ignore that this disqualification of the mind from the ability to question the postulates and review the sources is not rationally permissible – especially for the critical mind.

What Shahrour and al-Jabrī failed to realize is that we will not be able to transcend the discourse of political antiquity and liberate Islam from the magical worldview, if we do not transcend the set of foundational assumptions that make up the antiquated view of the Qur’ān.

The Holy Qur’ān is not ‘the word of God’ that descended by chance or by design from the invisible heavens, as the paradigm of religious antiquity would have it. It is, rather, the fruit of the human soul’s capacity to ascend and rise for the purpose of connecting. But unlike in philosophy the ascent here is not demonstrative, but rather intuitive, one based on the faculty of the imagination.

Prophethood, as Abū Naṣr al-Fārābī maintains, is the most perfect rank that man can attain to with his imaginative power.[4] And prophecy, as Baruch Spinoza adds, ‘does not require a perfect mind, but rather a fertile imagination’[5]. This means that the Holy Qur’ān is not a book written by God and sent down from the Kingdom of Heaven to the lowest of the heavens or to the ears of the Messenger. Rather, it is the fruit of an imaginary effort made by the faithful Messenger for the purpose of representing and interpreting the divine signs such as he grasped them from the stages of the divine emanation. If the levels of imaginative power vary according to the circumstances, then this was reflected in the Qur’ānic verses, which varied in their expressive subtlety and rhetorical precision. It is this discrepancy that has resulted in two levels of revelation, which are, according to the way the Qur’ān expresses it: āyāt muḥkamāt (definitive, decisive verses) representing the solid core of the Qur’ān, and āyāt mutashābihāt (allegorical verses) representing the most delicate circles in the Qur’ān.

The question now is: can we say that the Qur’ānic Text is a non-heritage Text, that is, one that stands above history, and therefore one that remains a contemporary Text for all ages and for all generations? Specifically, can we consider the political concepts and values contained in this Text, such as obedience, allegiance, tribute, shūrā, booty, fay’ (grant), alimony and so on, as contemporary issues for us as well?

What is required of us is that we remain aware, and acknowledge, that we are the children of this new world

The question may seem embarrassing, but what makes it so is that we have always considered the Qur’ānic text to be sacred Text that expresses the absolute ‘rulings of God’ regardless of time and place. This is a big mistake, indeed an original sin in the field of interpretation.

When we imagine that the Qur’ān is ‘speech, language and style’, in their full and literal sense, we end up sanctifying all the concepts and perceptions that they contain. The Qur’ānic discourse thus turns from a devotional discourse into a textual obstacle to modernity and modernization.

The dilemma occurs when we believe that the opposition between, on the one hand, the concepts of caliphate, allegiance, shūrā, imamate, and obedience and, on the other hand, the concepts of democracy, elections, voting, pluralism, and alternation of power is a confrontation between a religious or Islamic conceptual apparatus representing the essence of the Islamic religion, and a civil or Western conceptual apparatus representing the essence of western culture. That is, that the opposition appears to be one between the will of God on the one hand, and the will of the Western man on the other hand. This is also a very dangerous fallacy.

It is true that the Holy Qur’ān has used these old and outdated concepts within its communicative field. But use is not proof of ownership or possession. It is not enough for the Qur’ān to make use of any concept for us to say that it has therefore become a religious, Islamic or Qur’ānic concept, or that it is to form a deep-rooted matter of identity for us. The fact is, creating or reproducing concepts is not a function of the religious arena, and nor is it the function of the Holy Qur’ān. The production of concepts was, and still is, taking place within another arena of knowledge, which is exclusively that of philosophy, as Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze maintained.[6]

Islam is a belief-system whose aim is to exclusivize the divinity and render it transcendent in what is called the exclusivity of lordship (tawḥīḍ al-rubūbiyya). Apart from this intent, issues of Sharīʻa, transactions, the penal system, issues of ḥudūd punishments,[7] retaliation, division of inheritance, the female portion, a woman’s testimony, obedience to the ruler, guardianship of the husband, and along with these all the concepts and perceptions contained in literalist and textual Islam, these remain mere accidental and subsidiary interpretations of the spiritual and divine Islam. They fall within the cognitive context that suited the mental and emotional level of mankind as it was in the ancient world.

Suggested Reading

The ancient world was not an eternal world, nor was it destined to be. Rather, the destiny of existence is that ‘to everything that is completed there comes a diminution’[8], in the eloquent words of one of the elegiac poets of Muslim Spain. The old world is merely an accidental, relative and fleeting world, like all other human worlds. The Qur’ānic discourse expressed as much when it says: Everyone that is thereon will pass away.[9]

When we fail to represent this awareness of transience, passing away and contingency – which of necessity is the fate of all existence as Heidegger sees it, or the essence of the divine spirit according to Hegel’s premises, and indeed the essence of divinity itself as the Qur’ān explicitly states it when describing God as Every day in (new) Splendour doth He (shine),[10] when we fail to realize becoming and change as part of divine destiny, then nostalgia for the old world becomes a mere obsessive neurosis that engenders gratuitous violence and requires treatment.

The difference between the concepts of caliphate, allegiance, obedience, shūrā, imamate and community on the one hand, and the concepts of democracy, pluralism, elections, voting, and rotation of power on the other, does not lie in the fact that these are Islamic concepts that are religious, divine and unseen, or that these belong exclusively to Islam or described as Islamic – as opposed to civil, positivist, human, or western concepts as belonging exclusively to the West, or described as western. Rather, the difference lies simply and clearly in the fact that there is a conceptual apparatus that belongs to the old world, with all its various religions, cultures and authorities, as opposed to a conceptual apparatus that belongs to the modern world with all its various religions cultures, and authorities.

This clearly indicates and eloquently expresses how, when we decide to replace ancient political concepts mentioned in the Holy Qur’ān, such as the caliphate, the shūrā, pledges of allegiance, obedience, the subject flock, apostasy, tribute, people of the dhimma,[11] and other political (or specifically proto-political) concepts that belong to the ancient world and impede the development of democratic awareness and the values of political modernity – we are not abandoning divine or Qur’ānic concepts, as some imagine, but are simply deciding to move on from the political exploitation and ideological employment of concepts in a text that belongs to the ancient world, and which had no other function than that of worship.

Suggested Reading

When we take up modern political concepts such as democracy, elections, pluralism, the rotation of power, human rights and citizenship, we are adopting concepts that belong to the new world, which is the only world we have.

What is required of us is that we remain aware, and acknowledge, that we are the children of this new world with all of its concepts, perceptions and representations, and we were not born anywhere else than this world, the world of modernity.

As for the ancient world, the world of the ‘Abode of Islam’ and the ‘Abode of War’, the world of al-walā’ wal-barā’ (loyalty and disavowal),[12] the world of obedience, the group, the caliphate, al-fitna (‘sedition’) and other ancient concepts, we can put it no more eloquently than saying:

Those are a people who have passed away. Theirs is that which they earned, and yours is that which ye earn. And ye will not be asked of what they used to do.[13]

[1] See Glossary under ‘Qadar’.

[2] Dr. Muḥammad Shahrour, ، الكتاب والقرآن 9th ed. (2009) شركة المطبوعات للتوزيع والنشر Beirut, p.36.

[3] Muḥammad ʽĀbid al-Jabrī, مدخل إلى القرآن الكريم Part 1, دار النشر المغربية Casablanca, 2006, p.19.

[4] Abū Naṣr al-Fārābī, آراء أهل المدينة الفاضلة ed. Dr. Albert Naṣrī Nādir, دار المشرق Beirut, 1986, p.116.

[5] Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, tr. Ḥasan Ḥanafī, دار التنوير Beirut, 1st ed., 2005, p.129.

[6] The psychiatrist Félix Guattari and philosopher Gilles Deleuze have cooperated on a number of works focusing on the nature of knowledge and identity. Their work What is Philosophy? constructs a view of philosophy as based both on experience and a quasi-virtual world. (Ed.)

[7] See Glossary under ‘Ḥadd’.

[8] The citation is taken from Abū al-Baqā’ of Ronda (1204-1285) and his famous nūniyya poem lamenting the loss of several cities in Muslim Spain to the Reconquista.

[9] Qur’ān, LV (al-Raḥmān), 26.

[10] Qur’ān, LV (al-Raḥmān), 29.

[11] See Glossary.

[12] See Glossary.

[13] Qur’ān II (al-Baqara), 134.

Read Introduction to the Five Hypotheses here

Read Hypothesis 1 here

Read Hypothesis 2 here

Read Hypothesis 3 here

Read Hypothesis 4 here

Muhammad ‘Ābid al-Jabrī: “The Qur’ān not part of man’s historical heritage”