Renewal is listed in Arabic dictionaries in the sense of: ‘Bringing something that is not familiar or popular, such as creating new topics or methods that differ from a well-trodden and collectively understood pattern, or reconsidering popular themes and amending them so that they appear innovative to the recipient.’

IN MY CONCEPTION of renewal, I mean a new understanding of religion and its central role in life, a reconstruction of interpretative methods for the Qur’an and for religious texts, and a construction of religious scholarship in the light of philosophy, human sciences, society and the various arenas of modern knowledge.

The starting point for renewal is an awareness that the requirements of living in our time, and the challenges of life as it is, cannot be answered by what theologians, commentators, jurists and Sufis had to say in earlier times. Every age speaks with its own understanding of the sacred texts, and much of the conception is unable meet the needs of the mindset, spirit and heart of Muslims today. It is incapable of effecting a reconciliation between the Muslim and his or her aspirations in life as it is presently lived, nor can it produce a spiritual, moral and aesthetic vision of the world that can keep pace with the rapid pace of life and continuous change, or respond to what the mind, heart and soul of contemporary mankind demands.

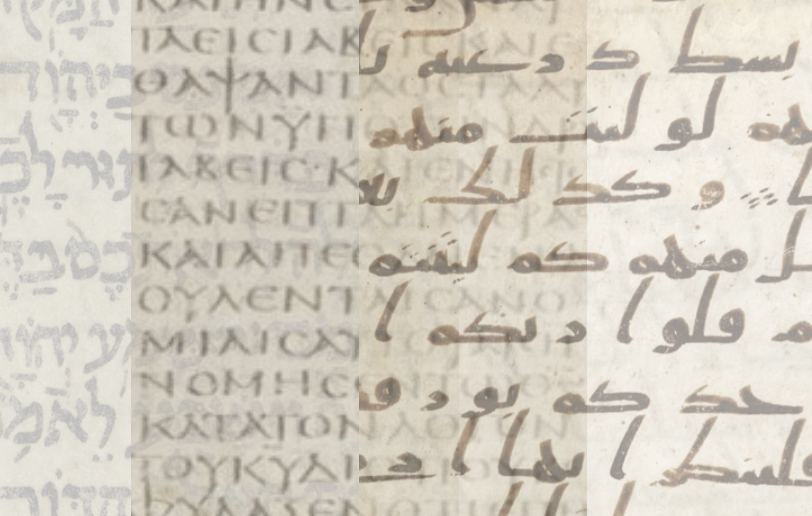

Renewal can be achieved only taking a new look at the deep infrastructure of the heritage, extracting what is vital and reviving, and passing over what is not. It must develop a type of understanding of religion and its texts that liberates them from the confines of history, and and at the same time frees the Muslim from his alienation from the present age.

Renewal can be achieved only taking a new look at the deep infrastructure of the heritage

The way we think, the theory of what knowledge is, and the tools by which we examine things, form the components in depth of the infrastructure of heritage, and it is these that exercise control over one’s perception of the world. Therefore, reconstructing knowledge and scholarship of religion must start from here.

A renewal remans re-discovering the theory of knowledge in Islam, in the light of which the religious disciplines were formed. Scholasticism (‘ilm al-kalam),[1] in my view, represents the theory of knowledge underpinning the subconscious infrastructure of the heritage. In this light, scholarship on usul al-fiqh (the sources of jurisprudence), Qur’anic scholarship, tafsir (interpretation), hadith scholarship, Arabic philology and its lexicography, and even Sufism, all these were subsequently governed in their perception of the world by the perceptions of Ash’ari scholasticism, along with other maxims of early scholasticism. These were termed ‘the mysticism (tasawwuf) of servitude’ as opposed to ‘the mysticism of freedom’, by which I mean the epistemological mysticism that lay outside the closed vision of early scholasticism and which created its own spiritual, moral, and aesthetic vision of the world. This Sufism of servitude – in their ziwaya,[2] their hospices, and khanqahat[3] – became saturated with the traditions associated with slavery, and hunted down the marginalised and the broken, and in later eras became widespread among the Sufi orders. In this Sufism of servitude, the Sufis adepts were enticed into a state of submission, surrender, and blind obedience to the elder of the order.

Early scholastic scholarship, usul al-fiqh, Qur’anic and hadith scholarship, the rules of tafsir relating to the Qur’an and religious texts, and the rules of conduct and behaviour in Sufism, imposed upon us as their product patterns of understanding, and it was in the light of these that our vision of the world has taken shape. It has had a significant impact on the way we govern our behaviour and determine our standpoints on things past, present and future. They also control the way we interact with others. All of these disciplines were produced by intelligent mujtahids[4] who spoke in accordance with the time and type of society they were living in. They excelled in employing the logic, philosophy, scholarship and knowledge available to them at the time.

I am using the term ‘renewal’ and not ‘revival’, ‘reform’, or ‘Salafism’. Some do not distinguish between these last three terms and ‘renewal and lump them together confusingly as one, as if they were synonyms.

Suggested Reading

The renewal that I understand does not call for a resumption of the heritage as the term renewal might imply, nor for the formal restoration of the religious scholarship nor the preservation of modes of thought and the tools investigation just as they are, as suggested by the term ‘reform’. Renewal does not call for accepting what is ancient without any sifting or evaluation, nor does it call for continued wariness and sensitivity to all that is new, as indicated in the term ‘Salafism’.

The pillars of a true renewal

Renewal, in my opinion, is something that has to be based on the following pillars:

The first pillar: studying, understanding, assimilating, and criticizing the inherited scholarship and understanding of religion, exploring its various circles of activity, its spectrum and its horizons, paying attention to the intellectual legacy in logic, philosophy, and theology, to the inherited spiritual, moral, and aesthetic perceptions in cognitive mysticism, seizing upon what is vital and living in the heritage, and freeing ourselves from simplistic and naive attitudes towards how we handle it – the way they are often seen as a quantity of texts to be adduced, memorized and repeated again and again, without thinking as to how these were to be organized, arranged and categorised, without any contemplation, analysis, interpretation, evaluation or scrutiny.

The second pillar: a critical assimilation of modern human sciences and knowledge such as: philosophy, psychology, sociology, anthropology, linguistics, hermeneutics, and other advances of the modern era, and an employment of all that is suitable as tools in reading and analysing religious texts – and benefiting from the way they can interpret how religion may be represented in the life of the individual and of society, or unlock patterns of personal spiritual experience.

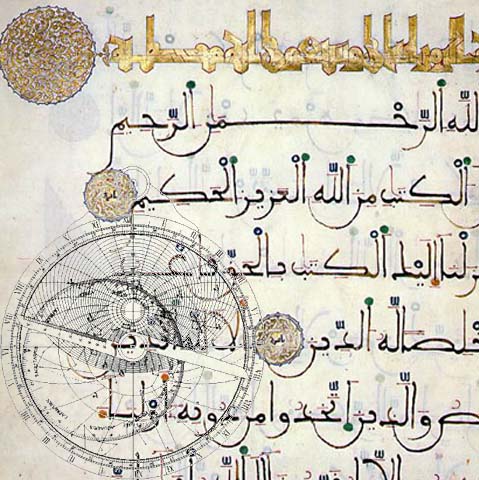

The third pillar: renewing the understanding of religion must be effected through engaging in the comparative study of religions and comparing their sacred texts, understanding how their religious institutions are formed, and how authority influenced the formation of the religious heritage and the diversity of the religious disciplines.

The fourth pillar: renewing the understanding of religion by studying the trajectories of religions through history, revealing the diversity in how its religiosity was expressed in different eras and societies, and uncovering the expressions and forms of religiosity in the lives of individuals and groups, and how this connected with the formation of inherited scholarship and the means of productivity for religious meaning.

Renewing the understanding of religion must be effected through by engaging in the comparative study religions

The fifth pillar: renewal begins with recalibrating the tools of knowledge production in Islam, in the sense that a renewal of the understanding of religion can only be achieved by renewing the methods of ijtihad,[5] and that requires penetrating deep into the infrastructure that produced these religious scholarly disciplines – that is, by sifting, evaluating and dismantling it, and by producing ijtihad methods for the various categories of religious knowledge that can keep pace with the accelerating rhythm of life.

The sixth pillar: the core of renewal lies in redefining religion, redefining its role in the life of the individual and society, redefining the spiritual, moral and aesthetic meaning that religion can offer mankind, and the kindness, compassion and mercy that religion can bestows on life, and the reassurance the heart and the soul that it can inspire.

The seventh pillar: renewal can only fulfil its promise by being freed from closed, literal interpretations of the verses of the Holy Qur’an and the religious texts, and by its interpretation being open to modern approaches in hermeneutics and linguistics, and to all the benefits to be derived from the results achieved by philosophy, human sciences and sociology.

The eighth pillar: studying the religious imagination, analyzing its formation, the channels by which it is nourished, and how far it is present in the production of religious meaning – these are also necessarily imposed by the process of renewal. Whoever owns the means of production for this imagination has power and control over the present and future of people in our societies. The religious imagination is vulnerable to being exploited for the purpose of consolidating and expanding spiritual authority and legitimizing political authority, and can act to increase its hegemony and reach.

The religious imagination plays a major role in constructing the spectrum of the sacred, and is directly reflected in human life and behaviour. It is an influential factor in the building of individual and societal culture, in unconsciously rooting structure into one’s consciousness, and in steering Muslim societies and their historical destinies. In our societies, this religious imagination exercises a wide-ranging power over the mind, potentially leading to putting that mind out of service or rendering it absent altogether. Only a critical thinking that places limits to the religious imagination, and works to employ it effectively to build and to develop, will succeed in restoring the authority of the intellect.

The religious imagination is vulnerable to being exploited for the purpose of consolidating and expanding spiritual authority and legitimizing political authority,

The ninth pillar: renewal does not begin with heritage only to end with heritage, as some of those who write and talk about renewal effectively end up doing. It does not start with actual reality and present the heritage as something that can answer to all that the present-day reality demands, without bringing about a catastrophe – since most of that heritage is alienated from present-day reality. As nearly two centuries of the incoherence and failure of such a call has evidenced, anyone who calls for starting from the heritage and returning to it as an act of ‘renewing and reconstructing the heritage’ ends up in a state of constantly renewed confusion. Such a man has simply been unable to dive into the heritage and pick up any treasures, and is unable to see a bright horizon before him where he leaves what is dead in the heritage, and deadly.

The ‘rebuilding of heritage’, I read in some intellectual initiatives, turns out to be no new construction inspired by anything that was rational, spiritual, moral, or aesthetic, or lively and reviving in the heritage, not is it gathered up and poured into an alternative mould in the light of the requirements of reality, one that relies on the achievements scored by philosophy, science, and modern knowledge. Instead it is often just a process of ‘appealing’ to heritage, to its vocabulary of terms and turns of phrase, and to its content just as it is, for all its repackaging with attractive titles and shiny banners.

Suggested Reading

It is rare that we find anyone who thinks in terms of an alternative system for producing religious meaning from the sacred texts, one that lies outside the space of inherited evaluation mechanisms and ijtihad methodologies. Much of what Al-Azhar and other institutions of traditional religious education puts out is repetitive talk about revival and reform, with no one outside of the institutes of religious education listening to it. Most of these screeds heap up words upon words, piling up tautologies, often entirely devoid of content. The mentally aware reader simply tires of them.

We need a deep critical review of this path of religious reform in Islam that has been repeated from Jamal al-Din al-Afghani right up to today, whose banner continues to confiscate every call for renewal. Deep criticism of heritage and its infrastructure, and its systems for producing religious meaning, can at times be heard hailing from outside these institutes, but any interaction with it remains marginal. Most do not listen to it, unless it comes from the consecrated religious establishment.

If religion is to fulfil its function in life today, we must understand it as life to be lived on new horizons of meaning. In the light of this understanding, any methodology we adopt should be established directly at the level of interpreting the Holy Qur’an and the religious texts, and at revealing the spiritual, moral and aesthetic meaning them needed for human life on earth. All that lies outside of that, mankind can derive from what reason, science and human knowledge demonstrates, and from what human experience has accomplished over tens of thousands of years.

[1] ‘Ilm al-Kalām (‘Kalām Scholarship’) denotes scholastic theology, the discipline of seeking theological principles through dialectic, that is, the seeking of philosophical demonstrations to confirm religious principles. The ‘Ilm al-Kalām developed as a rational theology, practiced by mutakallimīn. Its place in Islamic history still remains controversial, and modern Salafi scholars continue to outlaw it.

[2] A zawiya (zaouia in the Maghreb, pl. ziwaya) a building and institution associated with Sufis. It can serve a variety of functions such a place of worship, school, monastery or mausoleum.

[3] A Khanqah (pl. khanqahat) is a building designed specifically for gatherings of a Sufi community and is a place for spiritual practice and religious education. Its function is to provide the members with a space to practice lives of asceticism.

[4] A mujtahid is a scholar that exercises legal reasoning independent of what is literally prescribed by scripture.

[5] See Glossary.