There are some who claim that there is a difference between the extremist and moderate religious currents, while there is in fact no difference separating the moderate from the extremist religious discourse. Both start from the same intellectual premises and employ the same ‘devices’.

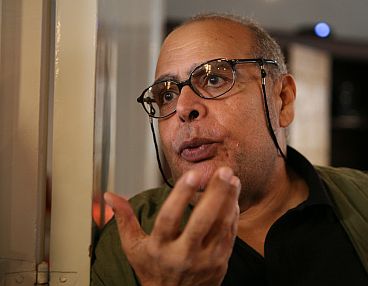

THE DIFFERENCE between them is one of degree, not of type. This is how Dr. Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd[1] characterised it, affirming that both discourses depend on basic fixed components in the construction of the discourse, components such as ‘takfīr’, ‘hākimiyya’ and ‘the Text’ which do not accept debate or discussion or any negotiation.

The dispute between moderation and extremism, according to Abu Zayd, is a merely marginal dispute rather than a fundamental one. It is a dispute concerning the scope for the application of a principle, not about the principle itself, or a dispute on the appropriate timing or circumstance. Thus takfīr is considered to be a fundamental building block of the religious discourse in both its moderate and extremist wings. This building block is clear and overt in the extremists’ discourse, while in the moderates’ discourse it is hidden and covert.

In fact the takfīr component has been used against the writings of Dr. Abu Zayd himself by both the moderate and the extremist wings. The last example of the use of this component occurred when the moderate and extremist religious groups in Kuwait came together to bar his entry into the country. The takfīr component has been employed against a large number of writers, thinkers, scholars, artists and religious figures across the Arab nation, and perhaps the most conspicuous target was the late Naguib Mahfouz.

Abu Zayd believed that, in essence, the call of Islam is a call for the establishment of Reason in the domain of thought, and moderation in the arena of social behaviour, as counters to ignorance and oppression. Similarly, he feels that the Islamic culture historically has assiduously demonstrated the absence of any contradiction between Revelation and Reason, in that the tradition is confirmed by the application of Reason, and Reason provides the basis for accepting the truth of the Revelation. In his view, the first attempt to banish Reason in favour of tradition dates from the Siffīn incident[2] when copies of the Qur’ān were raised aloft and the Umayyads had recourse to the arbitration of the Qur’ān. This may effectively be seen as a transferring of the dispute from the political arena to the domain of faith and the Texts. This transference has led to the downgrading of Reason in favour of a dependence on the Text.

‘The call of Islam is a call for the establishment of Reason’

This arbitration of the Texts in the political arena, according to Abu Zayd, prepares the ground for the ‘comprehensiveness’ of the Texts and their domination of the religious discourse. This in turn leads to the removal of the independent authority of Reason, and its conversion into a dependency fed by the Texts. In this way, Abu Zayd feels, the current religious discourse – the Salafist discourse especially – is not in fact supporting ‘tradition’ since it denies its epistemological basis, which is Reason. As a result Man becomes alienated from reality and the ground prepared for despotic rule of a particular kind. This religious discourse has prevented human Reason from communicating through deeper interpretation with a divine discourse that was “bestowed in the language of mankind.”

This is what has led to the deepening of the gulf between the divine and the human, and the re-fashioning of religious concepts by re-interpreting them so that they dissolve into an ideology of religious ‘governance’ (hākimiyya), an ideology which seeks to cancel the application of Reason and leave Mankind bound hand and foot to the power of a particular sort. The claim to a monopolization of truth, and the monopolization of decision-making based on this, may be seen as the theoretical basis underpinning the concept of hākimiyya.

Abu Zayd protested against the insistence made in the religious discourse on delimiting Mankind’s relation to God to a single end – servitude. Thanks to hākimiyya, this servitude turns into the enslavement of Man by a special class of man – the faqīh. That is, the investment of men claiming for themselves a monopoly of the right to understand, explain and interpret, on the grounds that they alone can convey the message of God, and the confinement of Man’s participation to one of obedience and compliance, with the right to question and debate denied him. Any contesting of the hākimiyya of the scholars of law is now labelled act of Disbelief, atheism or scepticism, and is to be seen as a blasphemous heresy against the rule of God. Such a process transforms the arena of contest from one of a battle between men to a battle between Mankind and God Himself.

The Texts are fixed in their ‘expression’ but fluid in their ‘concept’

Yet Islam, according to Abu Zayd, actually freed Mankind from the domination of his Reason by fantasies and legends, and liberated his conscience and convictions from anything that would inhibit his freedom. Faith alone is what is operative on the level of belief, a level which is one of heart and feelings, not one of interference, evaluation and judgement from others.

Abu Zayd raised the question of ‘the historical aim of the religious Text’, depicting it as a problem which the religious discourse is deliberately ignoring. This issue is related to the historicity of concepts which the religious Text raises, in that they constitute a natural product of the historicity of language in which this Text is formulated. This historicity embraces the purpose of the Text for society and the Text’s relation to what it denotes. According to Abu Zayd there are no essential, fixed components to the Text; rather, each

reading of its historical and societal meaning has its own essence which it reveals through this Text.

Suggested Reading

The revival of religious discourse – the missing human dimension

In order to revive understanding of the religious Text Abu Zayd seeks to go beyond the interpretations of the fuqahā’ and refuses to be confined to the ‘legal’ Texts to the exclusion of doctrinal or narrative passages. He stresses that a text, whether human or religious, must be evaluated according to established, consistent criteria, and that the divine nature of the Text does not immunise it from these criteria, since it has itself become ‘humanised’ after its embodiment in history and language, and directed towards Mankind in the form of its utterance and meaning.

The Texts, according to Abu Zayd – particularly those that were taken down and recorded from the moment of their inception – are fixed in their ‘expression’ but fluid and changeable in their ‘concept’. On the other hand texts that were subject to the mechanisms of oral transmission (that is, the Hadīth) lose this feature of fixity in expression. The intellectual and cultural horizons of the reader, according to Abu Zayd, have an impact on the understanding of the language of the Text and the working out of its significance. Nevertheless, the religious discourse recognises only an understanding that locks the meaning of the Texts into frozen templates. The religious Text – the Qur’ān – from the moment of its first appearance, that is, with its recitation by the Prophet at the moment of Revelation, changes from being a divine Text into a human reading, since it becomes transformed from revelation to interpretation. The Prophet’s own understanding of the Text represents the first of the several phases of the Text’s fluidity in its interaction with human Reason.

[1] Dr. Abu Zayd (1943-2010) was one of the leading liberal theologists in Islam. He is famous for his project of a humanistic Qur’ānic hermeneutics. In his work Dr. Abu Zayd argued that the Qur’ānic texts should be interpreted in the historical and cultural context of their time. The mistake of many Muslim scholars was to see the Qur’an only as a text, while this vision of the Qur’an as a text was the vision of the elites of Muslim societies, whereas the Qur’ān is equally important for the Muslim masses as a creative discourse. His work was the subject of a specific study aimed at establishing his apostate status. In 1995 he was found guilty of apostasy by an Egyptian court and after receiving death threats from al-Gamā‘a al-Islāmiyya moved to the Netherlands. (Ed.)

[2] Essentially a dispute on the legitimacy of the succession to leadership of the Muslim community. After the assassination of the Caliph ‘Uthmān (an Umayyad), his kinsmen opposed the election of ‘Alī as the next Caliph. The matter was put to arbitration on a religious basis in 657, a measure that caused disaffection among ‘Alī’s supporters who seceded. As a result of the disarray the Umayyads consolidated their position politically. (Ed.)

Main image: Qur’āns raised aloft – a transference from the doctrinal to the political