In this two-part essay we will address several problematic points facing scholars of the history of the beginning of Islam. These points will lead us to the larger question: What happened at the beginning of the seventh century AD?

WHAT ARE THE problematic points raised in the subject of Islamic studies or research on the beginnings of Islam?

Firstly: There is the issue of historical references. For any historical event, there is always the presence of the historical narrator or witness, who records the aforementioned historical incident or fact, which is crystallized later in the form of a historical document bearing witness to what happened. This is called a historical reference or source, and its credibility is often associated with its closeness in time to the event or its contemporaneity with it, alongside the objectivity of its record.

When it comes to the origins of Islam there is a major problem concerning the historical documentation, a real issue facing researchers specializing in Islamic history. Where are the documentary references associated with early Islam? The problem revolves around the emergence of Islam as a religion at the beginning of the seventh century AD at the hands of its founder the Prophet Muhammad bin Abdullah, an event that coincided with a period of documentary dearth. This constitutes a sizeable historical void following the death of the Prophet, a void that extends from the beginning of the seventh century AD to the middle of the ninth century AD – a period that extends from the advent of the Prophet to the emergence of the first documented Arab reference to Islam.

The first written reference to appear among Muslims, if we can describe it as such or rely on it as such, was the biography written by Ibn Hisham. his work chronicles the ‘sira‘, the life and deeds of the Prophet of Islam as far as was, in his words, orally relayed to him from Ibn Ishaq, who the sources mention was the first to pen a sira of the Messenger, but which work was lost. Ibn Hisham subsequently collected together what he heard from him, so that this first Arabic language biography was this work of Ibn Hisham, a man who died in the year 833 AD, that is, almost two hundred years after the death of the Prophet of Islam.

These religious sources were written for da’wa purposes, and are not examples of historiography

It is just a biography, since religious reference works were not penned as historical documentation, but rather as kerygmatic (da’wa) materials for the faith. As the thinker Hadi Al-Alawi says, these religious sources were written for da’wa purposes, and are not examples of historiography. It is as if were were to attempt to seek for a historical source, for example, in Al-Tabari as one of the most important and earliest historical sources in Islam (aside from the absence of any religious character), and given especially that he died in 923, that is, in the first half of the tenth century AD, this means that we are three hundred years removed from the founder of Islam, Muhammad bin Abdullah.[1]

Here is where the void lies, a void that has to be filled through objective, rational research and evaluation. What is the value of a historical document written three hundred years after the death of the actor in the historical event? In addition, a major impact that we cannot ignore in these three centuries, is the oral legacy of stories that have come down to us relating to the conflict that broke out following the death of the Prophet Muhammad, the founder of the new religion. In this conflict is embodied the Muslim-Muslim clash, represented by the Great Fitna, the sedition that took place at the beginning of the time of Caliph ‘Uthman, and then continued in the Umayyad-Hashemite conflict the Umayyad-‘Abbasid conflict and the ‘Abbasid- Hashemi conflict.

At this point, after centuries intervening from the historical event, and the many conflicts that broke out between the various Islamic parties, who is able to guarantee that the texts and events were not altered by each party according to their interests?

Here is where the biggest problem today lies, a problem caused by obscurity or ambiguity caused by our inability to form an understanding of the development of Islam as a new religion appearing in the Arab region at the beginning of the seventh century AD.

We have another problem related to Islamic references, something other than their time-lag from the historical events. Although these Islamic references appear to be many and varied in their sources, they suffer from the problem of being attributed mostly to a single historical source, one that is centered on the sira of the Messenger and relies for the most part on the testimony of Ibn Ishaq or Saif bin ‘Umar for its historical attribution and documentation. Here we see that the Arabic sources go back to one sole source, which presents a credibility defect given the absence of an alternative source, or an alternative point of view.

This issue has also spawned other questions leading to a great deal of confusion as to how to deal with Islam. These questions need to be answered, given the fact that there is no real historical reference or document for the period of early Islam upon which we can rely on scientifically. In this respect we feel that Islam will be like Judaism: despite Islam’s greater influence and global status today, it remains as an oral heritage unsupported by anything, much like Judaism which lays claim to the ownership of history, even though modern archeology is unable to confirm whether the characters of the Children of Israel existed or not.

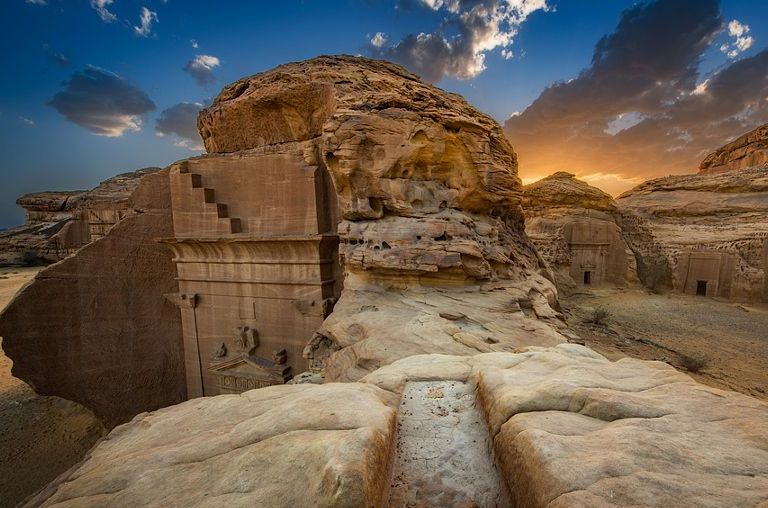

Would anyone venture to conduct excavations in Makka and Madina near to the Two Holy Mosques, so that archeology can have its say in the matter?

Islam too, with its holy book, presents the same problem of gaps and an inability to connect them with a scientifically established material reality. The problem today is one of archaeology: would anyone venture to conduct excavations in Makka and Madina near to the Two Holy Mosques, so that archeology can have its say in the matter? Is there much to be expected from excavating the cultural remains of Bedouin communities?

Secondly: There is the issue of the Arabic language – the language of the Islamic sources. During the period of the emergence of Islam Syriac had been the spoken and written language in the Arab region for 16 centuries. The written Arabic that we know now had yet to appear in anything other than an oral form. There is also the problem of how its letters were derived from, and altered the form of Syriac or Nabataean letters, changing its shapes and forms several times, until getting to the form that we know today.

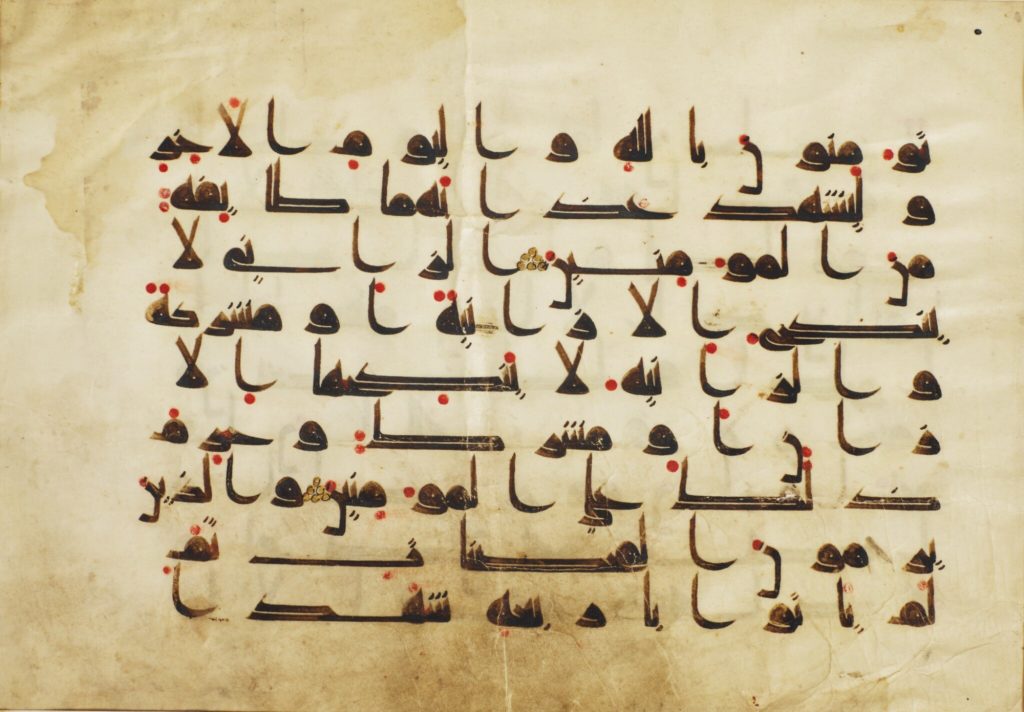

And we have still another issue: the punctuation and formation of the Arabic language at a late stage after the emergence of the Qur’an and the New Message, first at the hands of Abu Al-Aswad Al-Du’ali , and later at the hand of Al-Farahidi. This script development in step with the development of the Arabic language bequeathed some major problems, in terms of the copyists’ space for error and their suspected confusion between similar letters, distinguished only by a dot, and how one may alter the meaning of the word simply by changing the position of the dot. We have a majority of letters whose form does not change according to their position in the word, and others that are not differentiated in writing, except by the position of the dot such as the letters; ب، ت، ث، ن، ي (y, n, ṯ, t, b) in their initial and medial forms, and also ج،ح،خ . (ḫ, ḥ, j) in all of their forms and ق، ف (f, q) in their initial and medial forms. This problems adds to the problem of the Arab sources and the many periods in which they were copied, the holy text included. For the Qur’an was also exposed to these problems of letter forming and diacritics.

It is also taken for granted that the Qur’an was subject to differentiation in the length and number of its verses from the stage of the Qur’an as it was at the time of the Prophet Muhammad – preserved as it was orally and in the presence of believers or memorizers of the text dispersed over many parts of the Islamic state before such time as it was written down a relatively long time after the death of the Prophet Muhammad – and the stage of the writing of ‘Uthman’s Qur’an, which is the text of the Qur’an that we have today.

Suggested Reading

Similarly, there are many grammatical problems in the text of today’s Qur’an, in terms of whole words or their grammatical forms, yet it is surely not possible for God to make grammatical mistakes in several places in the Qur’an!

This is a problem related to the stages of the development of the Arabic language and its later forms and punctuation. The transcriber and recorder of the text perpetuated changes to the language from his lack of understanding or his uncertainty as a result of the issue of the development of the forms of the Arabic letters.

All of these things need patient scientific research in and of themselves, let alone the amount of extremism that is being engendered from ignorance and the lack of an understanding of these issues. The Arabic language before punctuation is not the same Arabic after punctuation, for the word جنب (‘side’) in the Arabic language is not the same as the word جيب (‘pocket’), and the difference between the two is simply where you place the dot – above, or below, the middle letter.

[1] Hadi al-‘Alawi, ، شخصيات غير قلقة في التاريخ الإسلامي Beirut, 1995.

Further reading:

F. Rosenthal, A History of Muslim Historiography, Leiden 1968.

C. Luxenberg, The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran, Verlag Hans Schiller, Berlin 2007.

J. Healey, The Early History of the Syriac Script: a Reassessment, Oxford 2000.

Main image: Kufic Qur’an (Surat al-Nur, verses 2-6), 9th c. AD.