In the eighties of the last century, the late Sudanese politician and diplomat ‘Alī Abū ‘Āqila Abūsan wrote a pamphlet entitled “Al-Turābī’s Letters and the Contemporary Islamic Movement,” which included seven letters sent to him from the British capital by the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan, Ḥasan ‘Abdallāh al-Turābī, from December 1955 until March 1958. At the time, al-Turābī was on a scholarship to obtain a master's degree from the University of London, while Abusen was a student at Dār al-ʽUlūm College in Cairo.

AL-TURABI’S LETTERS included many topics, including his personal feelings about self-fighting, supplication, and not being in a hurry to win the world, in addition to his comment on some events such as the tripartite aggression against Egypt and the bias of the Western media, as well as his criticism of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe. The bulk of the letters contained al-Turabi’s views on criticism of social life in the West and his firm belief in the end and collapse of Western civilization.

In his first letter, written on December 8, 1955, Al-Turabi describes to his friend English society, saying:

“I think you can imagine the conditions in which we live in London, the extent of the decadence in the morals that control people, the values that control them and the opinions that prevail in society, behind the monotonous words that they exchange: “Thank you – Please” there lies a psychology that does not know brotherhood and disavows generosity, altruism and the meanings on which oriental society is built.

Behind official eating manners the simplest rules of hygiene are absent, and behind the so-called democracy lurk strong selfish tendencies, manifested in their opinions about people of colour and about those ‘criminal’ peoples who call for their freedom. I do not want to mention women, for that is the key to corruption in this life.”

If Al-Turabi was writing the above speech in the light of the colonial era that was dominating the continent to which he belongs and his country Sudan, one of the British colonies, it might be understandable if his speech was thus characterized by a kind of bitterness and hostility to that colonial country. But there are no objective reasons to accord absolute preference to eastern over against western communities in this sort of silly comparison particularly in the realm of values (generosity, altruism and so on) which are, by nature, relative.

It is noteworthy that Al-Turabi does not address the important aspects of the behavior of the English and of Westerners in general, such as respecting order, respecting time, reverence for work, not lying, appreciating privacy, and not interfering in the affairs of others, and so on. These aspects of behavior are usually what attracts the attention of the easterner when he comes into contact with these societies, due to their absence in his society

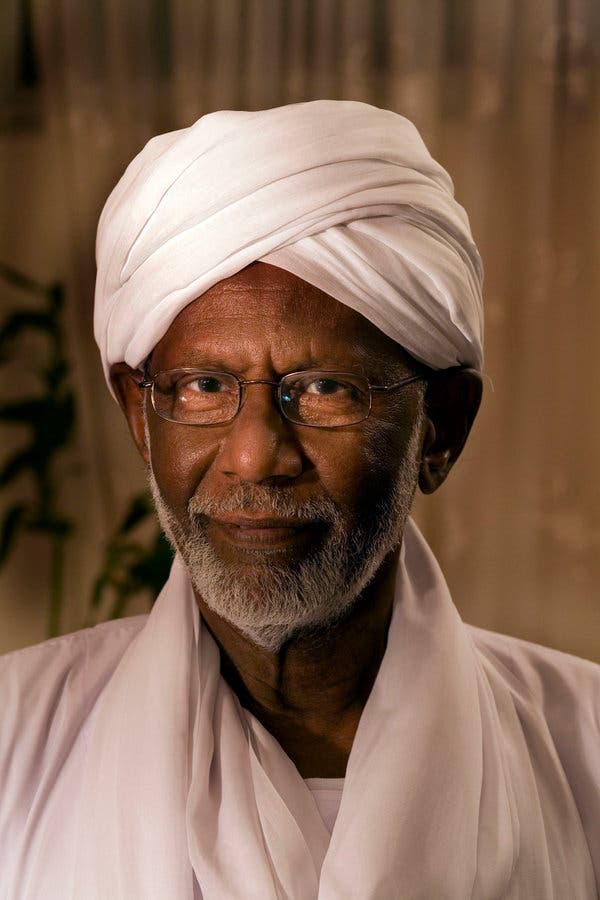

Western societies are full of humane norms that are difficult to square with Al-Turabi’s description

On the other hand, Western societies are full of humane norms that are difficult to square with Al-Turabi’s description and generalization concerning “the extent of the decadence in morals that control people and the values that control them”. For example, to prevent pregnant women or the elderly (men or women) or invalids from taking priority in a shopping queue or a bus or accessing special services is considered an impolite act for Westerners as well as for Easterners alike.

And when Al-Turabi describes in his above message women as “the key to corruption” in Western life, he resorts to talking about her at length in his seventh letter, written on March 7, 1958, in which he says:

“Women – and this is a calamity – come from all over Europe to find work and find husbands, but they also take up friendships, and some go to extremes in adornment and allurement, to the extent that three-quarters of the market is dominated by women’s fashions, hats and shoes. They associate equally with blacks and whites – since hedonism knows no colour.

On New Year ‘s Day they I was told while I was in Cardiff that thousands of people gathered and something happened that is unthinkable in the East, yet this is their custom when they celebrate the birth of Christ, which should call for abandoning pleasures, purifying the soul and eradicating lusts. And imagine the ugliest forms of licentiousness, and you will see what actually takes place on this occasion and others like it. I wish I knew how this constitutes the ‘emancipation’ or ‘progress’ of women that misguided eastern women strive for. If only they knew the status of women here, their loss of dignity and humiliation, and that all these feminist revivals in the East are but a cloak for personal purposes related to the nature of womankind.”

Since Al-Turabi does not see in Western women anything but the first opening point to corruption and licentiousness, and bemoans the loss of her dignity and humiliation in those societies, it is clear that this judgment was based on his psychological predisposition that caused him to unleash all manner of negative judgments upon the West. We can see this confirmed by his letters that show his lack of any real contact with the English; he does not refer to any friendships he has in London other than to his relations with the Sudanese and Arab and Islamic communities, and there is no mention of his attending theatres, cinemas, art galleries or operas, or even the New Year’s party they told him about, but which he did not actually attend!

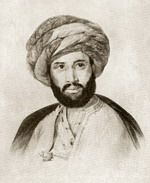

He paid attention to the education of women in French society, and their remarkable presence in the public sphere, to a level similar to men

In contrast to Al-Turabi, the great religious reformer and enlightened open thinker, Rifāʽa Rāfiʽ al-Ṭahṭāwī traveled to Paris in 1826 – that is 130 years before Al-Turabi’s visit to London – and he mingled with the French, as evidenced by his accurate description of their homes, private and public parties, dances and theaters. Despite their liberation, he did not see them as decadent and degenerate, and about women he said in his work Takhlīṣ al-Ibrīz fī Talkhīṣ Bārīs (A profile of Paris):

“There are women here who have written great works, and some of them are translators of books from one language to another employing fine eloquence and style, and some of them models of astonishing literary style and epistolary art. Hence the strength of some proverbs to the effect that ‘the beauty of a man lies in his intellect, while the beauty of a woman lies in her speech’. This does not apply in these countries, where a woman is judged according to her intellect, her genius, her understanding and her knowledge.”

Al-Ṭahṭāwī also defended the differences he saw in French society and denied that these were the cause of corruption:

“The confusion regarding women as to their chastity is that this is judged not from how much of themselves they reveal or conceal, but rather from the level of their education, and how far they retain affection for one person alone as opposed to sharking their affections, and from the level of compatibility between husband and wife.”

More importantly, he paid attention to the education of women in French society, and their remarkable presence in the public sphere, to a level similar to men, as citizens who share their rights and duties equally with men. It is this that he became engaged with, in transferring it to his home country Egypt, where he became one of the first advocates for the education of Egyptian women, and to which cause he authored the work The Faithful Guide for Girls and Boys which was adopted in schools for boys and girls.

Suggested Reading

What we are seeing here is an individual, an Azharī shaykh no less, who traveled to Europe with an open mind, something which allowed him to delve into the details of Western society, and which prevented him from engaging in absolutist value judgments. A woman uncovering herself did not indicate her degeneracy, rather her reliance on education was the important thing. Nor was the beauty of a women conditional on her speech, but more importantly it was a feature of her intellect, just as her leaving the house in search of education and her occupying the public space did not constitute the key to the corruption of society, as Al-Turabi holds.

As for France, where al-Ṭahṭāwī resided and returned with many benefits and lessons to transfer to his country Egypt, Al-Turabi writes it off, based on a brief trip, as an “immoral” country. His fourth message, dated October 27, 1956, puts it like this:

“Perhaps you have heard of our journey to the countries of the East and Europe, for I have described it to some brothers, but there is no lesson in the notes of a passer-by, other than to say that some countries are inhabited by a people who force you to recognize their strength and frighten you at the speed of their development, countries such as Germany. And to recognize on the other hand the poverty of other countries in terms of wealth, hygiene, and the social strength of the people, such as the immoral and helpless France that tyrannizes our brothers”.