The reform of Islam today is both essential and possible; what is lacking is political courage. It is true that the age of the religious intelligentsia, both in traditional Islamic circles or in the circles of political Islam does not make adaptation to the world we live in an easy matter.[1] But courage is nevertheless required, the courage of an intelligentsia that has a clear vision for the future, and who can with decisiveness lead their peoples.

ACCORDING TO IBN QUTAYBA consensus – that is, the consensus of the nation’s élite (or legislative powers in the contemporary sense) – “are more important than the Hadith in matters of legislation” [2]. So the reform of Islam does not need a text but rather the consensus of the decision-makers that it is necessary and in the nation’s interest. As al-Shātibī maintains, “Where the interest lies, that is where God’s law resides.”

The reform of Islam is the ultimate priority. Because in order to embark on its reform it requires the success of other initiatives which might appear to be unconnected to it – such as economic reform, for example. The reform of Islam initiative is not incompatible with the launching of other initiatives but is rather at one with them and their requirements. All reform initiatives follow on from each other in close succession, as the scholars of yore were well aware of. Political, social and educational reform initiatives, all these are an integral part of the reform of Islam. The common denominator among them is that they all require, as an absolute priority, the reform of the decision-making process.

The primary cause for our being left behind, or more precisely our long floundering about in the modernity crisis we are undergoing and our inability even now to emerge from it unscathed, is bad decision-making. In at least nine out of ten Arab countries decisions are not being made by institutions as some scientific industry in which the computer is the prime manufacturer, but rather by the whims and ravings of a single ruler.

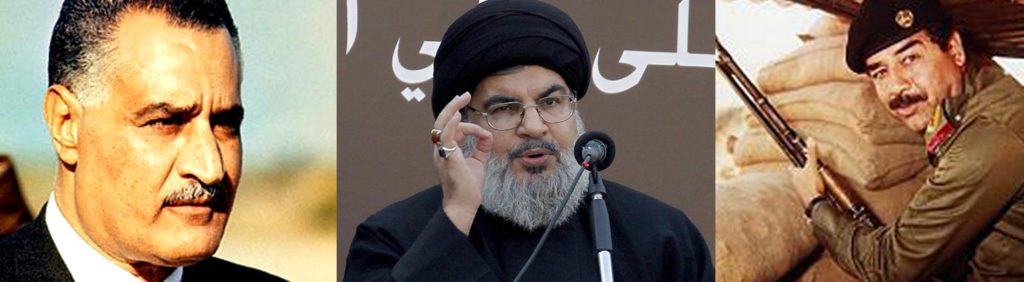

To take one of dozens of examples, Saddam Hussein boasted that he made his decision to annex Kuwait – disastrous both for him and Iraq and the entire Middle East – on the basis of a dream adding that (following a Hadith of the Prophet) a true dream constitutes one of the forty ingredients that make up prophethood. But the angel who revealed this dream to him had forgotten to recommend that he pose another, central question which the decision-making process demands: “And what about the morning after?…”

It was the same question that Gamal Abdel Nasser before him failed to pose when he expelled the international forces stationed along the Egyptian-Israeli border in May 1967, and which was the cause of the Six Day War. Nor was this question posed afterwards by Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah when three Israeli soldiers were kidnapped, causing the 2006 war. Nor did Hamas pose it when they refused to renew the truce with Israel, whose government then took it as a pretext to launch the war in Gaza in 2007. In fact, the road of Arab-Muslim defeats ever since their collision with colonialism has been strewn with emotional decisions born of a type of superficial thinking that demands that pipe dreams turn into visions of reality, and fantasies turn into facts. All the achievements of modernity, right from five centuries ago until now, have been effected by the type of courageous, intelligent political decisions that the Arab intelligentsia has yet to discover.

An absolute priority is the reform of the decision-making process

By courageous and intelligent I mean realistic, that which is inspired by the reality of the times we live in, as opposed to reckless and stupid decisions improvised under pressure of events that burn us, since these decisions are usually inspired by the decision-maker’s irrational fears or delirious gut-reactions. This is particularly because of the fact that the mot regular thing that binds Arab and Muslim rulers is paranoia. The world we live in is complex and unpredictable. To approach with improvised and irrational decisions equates to committing harakiri. To be courageous and intelligent means recognizing that one’s wishes and reality rarely coincide, that is, that the pleasure principle and the reality principle are opposites. But this remains to be grasped by Islamists and nationalists who are still talking to themselves and deceiving themselves as to the facts of the age they are living in.

The relationship of religious reform to decision-making

This is a close relationship. Arab decision-making has rarely respected the first principles of this art, which is exact definitions and mathematically accurate equations, concerning what is in the national interest, and exact calculations of the costs and benefits of any profit or loss with respect to every decision. It has ignored the four strategic areas, namely the reform of Islam, scientific research, technological innovation and quality education to international standards. Religious reform initiatives today are pre-supposes an understanding of the terminal, tragic dangers inherent in any problem that poses itself to us for the sake of changing course when the time is right.

Suggested Reading

The survival of Islam without any reform, that is, without separating religion from the state in order to avoid the dangers of sectarian and religious wars – particularly a Sunnī-Shīʽī war which could, at one stage or another, become a nuclear conflict – or without separating Sharīʻa law from positive law and making the latter the only law applied, will only plunge the Muslim world into the barbarism of applying corporal punishments, something which Freud, when discussing he practices of the Nazis, defined as “pre-historic barbarism.”

Without freeing scientific research and literary and artistic creativity from religious censorship ‘the clash between the Qur’ān and science’ as Dr. Abdel Sabour Shahin called it, will go on for ever. Without a separation made between the believer and the citizen, Muslims will remain more and more stand accused by global civil society of repeated violations against human and civil rights, and for treating women as noxious insects, and their minority communities as ahl al-dhimma[3], and the rest of the world as an ‘Abode of War’ promised the jihad that Islamic terrorism now takes as its name, and which casts a negative image of Islam not only among global world opinion but also among sections of the Muslim community itself.

Religious reform derives its legitimacy from its potential to block the path that leads toward tragic conclusions. It can attune Islam to the modern era which, if one were optimistic, is headed toward a single human civilization that will be marked by shared, universal human values and by basic standards for co-existence in a globalised world in which human destinies have become intertwined through thick and thin to the point that the question of regional government and the world government or ‘global confederation’ as the philosopher/anthropologist Edgar Morin termed it, has become a legitimate question, if we are to face up to the challenges expected for the survival of civilization and indeed the survival of the human race.

Areas of weakness in the condition of Muslims that religious reform can resolve

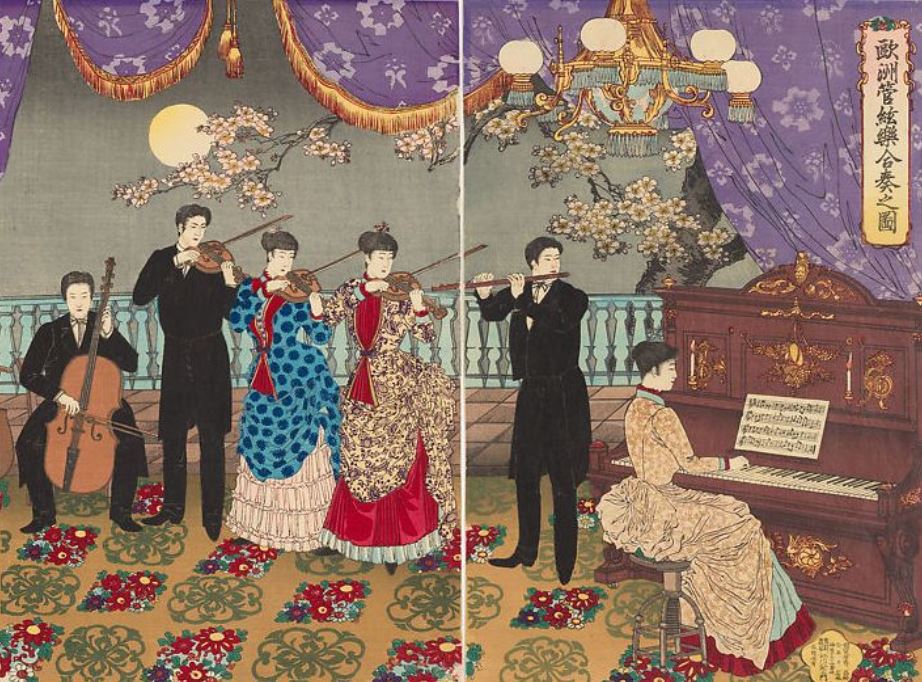

Islam has still not yet overcome the challenge of the three obstacles that Renan diagnosed in the nineteenth century: 1) the contempt for positivist science, 2) the refusal to engage in rational research into its texts, including the word of God held to be immune from scientific evaluation, or authoritative figures considered to be above questioning, and 3) the conflation between the spiritual and the temporal. These are religious, intellectual and psychological barriers allied to the suppression of religious, political, economic, scientific, literary and artistic creativity. For example, painting, sculpture and music are still prohibited in Islam. Judaism, from which we have taken these hysterical taboos has shed them, fortunately for Jewish believers. But we are still nailed to the floor by them.

The road of Arab-Muslim defeats has been strewn with emotional decisions born of superficial thinking

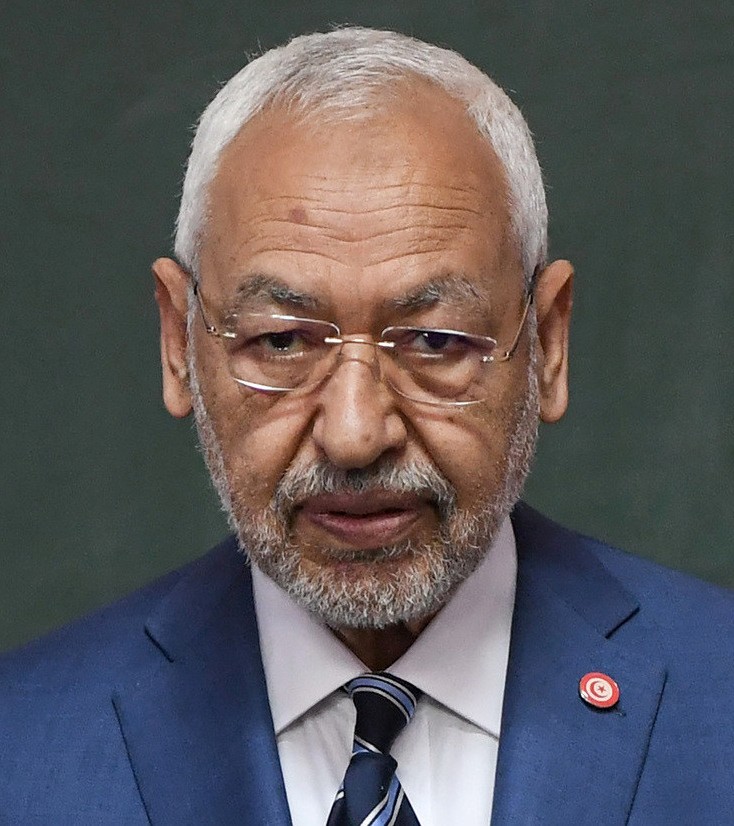

Judaism has also shed the bloody punishment of stoning, although we have also adopted it from them despite its non-appearance in the Qur’ān and the incoherence of the accounts of the Prophet stoning adulterers. Iran, Saudi Arabia and the ‘Sharīʻa Shabāb’ in Somalia still carry out stonings. Prince Khaled bin Sultan, the Saudi defense minister, in 2001 prevented me from writing for the newspaper Al-Hayāt “Life”, for calling ‘in the peninsula’ for international intervention to prevent stonings in Iran, on the grounds that Saudi Arabia also practiced stoning and would therefore also be included in the call for international intervention. In an article signed by him the President of the Tunisian Al-Nahda party, Rachid Ghannouchi, said that Islamic corporal punishments such as flogging were more merciful than European prisons. Why then should stoning not be more merciful than European prisons? The Islamic world is still walking on its head, and in the reform of Islam we are simply attempting to make it walk on its feet again.

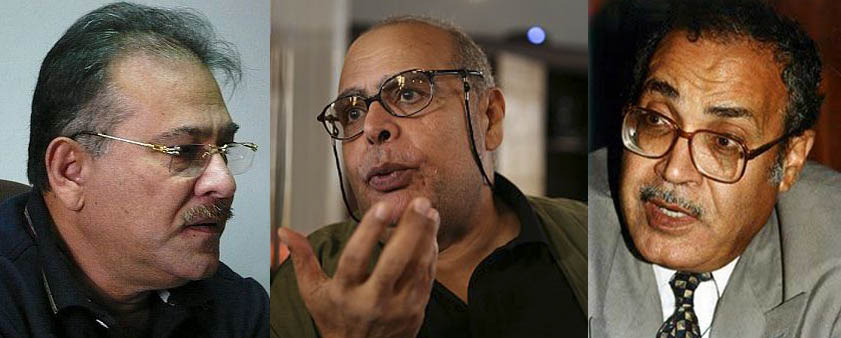

It is true that Renan’s charge can apply at least to all monotheistic religions, but Judaism and Christianity have finally overcome the three challenges. For instance, archaeological studies in Israel have discovered that what were held to be historical facts in the books of the Old Testament were legends, such as the Exodus from Egypt, Moses’ parting of the Red Sea with a stick, the Temple of Solomon (who has turned out to be a legendary figure) and King David, long regarded as a historical figure but now considered to be semi-legendary. In this context it would not be a bad idea to translate the book The Bible Unearthed by the Israeli archaeologists I. Finkelstein and N.A. Silberman. Fanatical Jewish religious authorities protested at the work, but Israeli scientists have not been brought to trial or prosecuted in the way Dr. Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd has ben prosecuted in Egypt, nor have any fatwas calling for their death been issued against them in the way that Muslim clerics have done. Nor, of course, have any of them been assassinated in the way Farag Foda was assassinated, with his killing subsequently justified by one of the luminaries of political Islam Mohammed al-Ghazali under the charge of apostasy. Not long ago the Al-Azhar Research Council called for the prosecution of Sayyid al-Qimny and Hasan Hanafi[4] because of their views. We are still crucifying Al-Hallāj and flaying alive al-Suhrawardī,[5] and persecuting Sufis and philosophers.

Suggested Reading

Muslim faqihs have been unable to overcome these challenges because they lack the ability to adapt to the modern world. Their primary jihadistic energies have turned into a barrier and they are incapable of acquiring the new dynamism required by the current era in history – a dynamic of adaptation to anything new that history brings. When religion lacks the ability to adapt and to be dynamic it sinks into religious stagnation.

And by religious stagnation we mean the prohibition on questioning and the imposition of ready-made answers held to be valid for all times and places. This is the static certainty, silly thinking and naive faith of the senile. A senile faith may be alright for the senile, but is no use for researchers. It comes from an incapacity to develop and generate new ideas. At the same time it is a fight against the few renovators that appear from time to time, such as Shaykh Najm al-Dīn al-Tūfī al-Hanbalī who was imprisoned and whose books were destroyed, against Sufis and philosophers who strove in their time for the reform of Islam and whose efforts at times cost them their lives, such as al-Suhrawardī and al-Hallāj, and people such as Muhammad Abduh at whose death Al-Azhar obstructed the funeral prayers for half a day, and Al-Tāhir al-Haddād whose funeral could only be attended by a mere handful of friends.

We are still crucifying Al-Hallāj and flaying alive al-Suhrawardī

To give a personal example: I have donated my body to science, to the medical faculty of any country that I happen to be in when I die. But when I delivered my will to the head of the nursing staff of one of the hospitals in Paris she replied: “that is if the medical faculty accepts it, since they often refuse due to the large number of donors.” Now compare this with the prohibition by the religiously inert fuqahā’ of the dissection of bodies. In 1973 Syrian medical faculties had to import corpses from China at a cost of US $ 1,000 each. This nailing down by anti-scientific jurisprudential rulings is a symptom of a Pharaonic cult of the dead – as the comparative history of religions teaches us, a cult that makes Muslim fuqahā’ despise the living body and sanctify the dead one. This incident alone should incentivize us on the need to accelerate the reform of Islam whatever the cost.

[1] The article is taken from a discussion with Lafif Lakhdar by Nacer ben Rajab and Lahsan Ouarigh, and forms one of the essays of his comprehensive Reform of Islam project.

[2] Ibn Qutayba (828-885 AD), was a renowned Islamic scholar and polymath who served as a judge during the Abbasid Caliphate and known for his work on the problems of tafsīr or Qur’ānic interpretation.

[3] Subordinate, ‘protected’ communities. See Glossary.

[4] See their numerous articles for Almuslih.

[5] On these see the article for Almuslih by Talʽat Radwan: Enmity to philosophy and cultural backwardness .