Many scholarly studies have recently been published on the history of the Qur’ān and the early history of Islam. Their common denominator is primarily one of a response to the assertions of Muslim proponents concerning the uniqueness of the Qur’ān, and the history and specificity of Islam.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

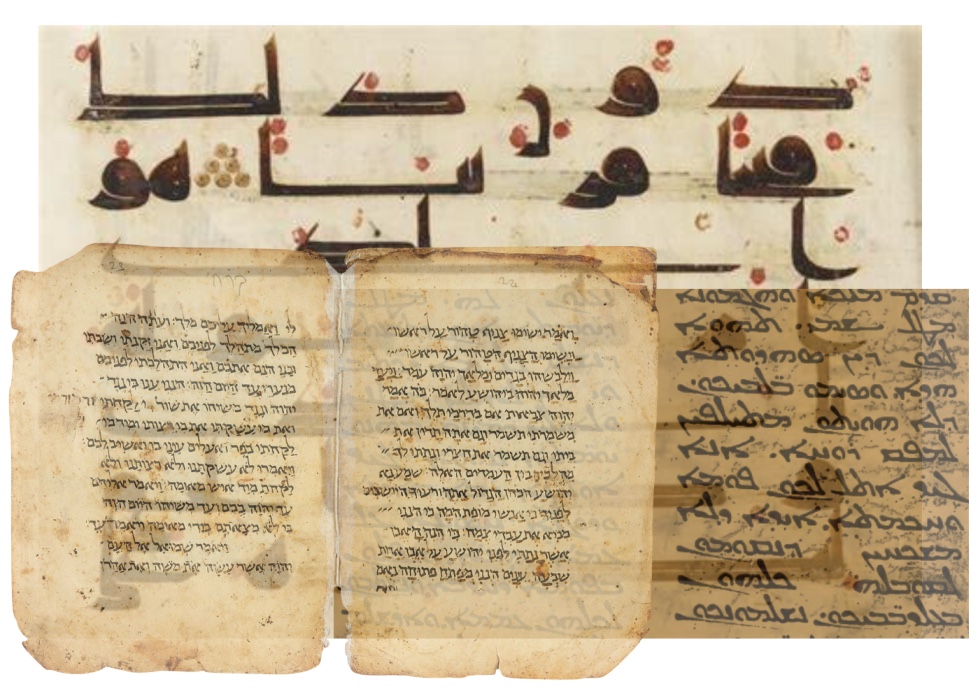

SOME OF THESE STUDIES feature the accumulated conclusions and questions posed by the latest research into the sources of the Qur’ān, and collate together the maximum amount of works in philology, archaeology, documentary evidence, Qur’ānic scholarship, the history of religions, and historical annals. This is based on the idea that it is only by placing texts in their contexts, and by combining specialist disciplines, is it possible to achieve a coherent conception of the true origins of the Text of Islam and uncover its true nature. This is because a number of studies have concluded that behind the Qur’ān lies a series of incorporated and paraphrased passages that were originally inspired by the Bible, the Talmud and the Midrash.

The ‘Mother of the Book’ has been implicitly encountered: it is the Bible

As a result of these researches the ‘Mother of the Book’[1] has been implicitly encountered: it is the Bible – which the original Qur’ān constantly refers to, as if the Bible and some apocrypha served as its foundation and matrix. We come face to face with Arabic-language apocrypha – the original Qur’ān – with its grammatical structure, its parables and its religious teachings. We find strong and striking echoes of Eastern Christianity during this early period of the Qur’ān and, in the view of the most important specialists, one third of the original Qur’ānic substrate may be made up of Christian hymns. The book The Three Faces of the Qur’ān specifically explores a range of hypotheses to explain this strong presence of biblical and ritual texts in the Qur’ān.[2]

Now this may indicate either the existence of earlier texts common to two religious communities at the time – the Nazarene Jews and the early Muslim sects – or it may point to the direct influence of Christian and Jewish Nasserite communities on the societies of primitive Islam. Or it may indicate the resurgence of biblical metaphors and ideas in societies of the Holy Book whereby a charismatic leader emerges leading an eschatological religious campaign under the prevailing conception of an impending apocalypse. This may help explain the complex, syncretistic and mythological nature of the Qur’ānic text.

The Qur’ānic text as something ultimately subject to temporal authority is not without its problems for its spiritual and divine claims

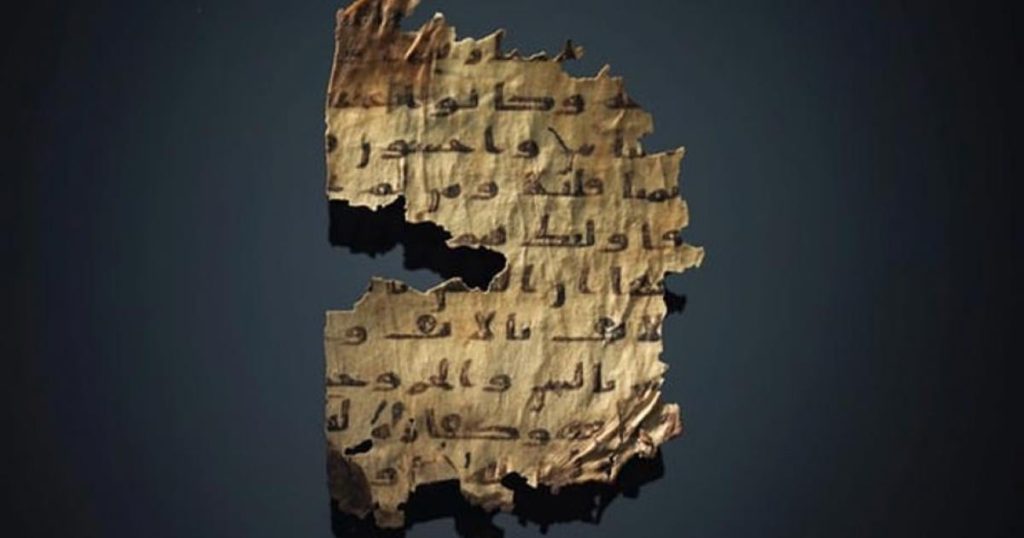

Based on this, attention has focused on the problem of how to distinguish the various layers of the Qur’ānic text’s composition over the centuries, and the considerable amount of reconfiguring and reinterpretating of oral traditions, borrowed Christian and Midrashic texts and the prevailing Syriac sermonising literature of the sixth and seventh centuries AD that went on.[3] This is what has led some researchers to believe that there was some extensive synthesizing activity taking place in the developing formation of the Qur’ānic text (the first phase, or first stratum).

Some have set out to trace the course of this activity, especially for the period following the establishment of the caliphate, and have attempted to highlight the additions that were made during the 80 year-long caliphal age (the second phase, or second stratum), in addition to intensively examining the orthodox tafsīrs. Particular attention has been paid to the commentators of the period of the ‘Abbāsid Caliphate who, in the view of many researchers, were responsible for giving meaning to this diverse process of collation (the third phase and final stratum in the formation of the Qur’ānic text).

Suggested Reading

The second stratum of the Qur’ān was produced, according to some, following the death of Muḥammad and was motivated by ideological, historical and tribal interests. The additions of the tafsīrs of the ‘Abbāsid Caliphate two centuries later put the final touches to this shift in the original collation. This is why, according to some, the nature of the Qur’ānic text is entirely contradictory and was ultimately subject to the establishment, support and consecration of temporal authority. This is not without its serious problems for its spiritual and divine claims.

Some have conceived that the Islamic world is destined to collapse because it is entirely based on a mythical idea

Based on this perspective, one can grasp the reasons why the Qur’ānic text is viewed, in the final analysis, as doomed to appear nothing more than a justification for unlimited political violence – given that it originated primarily in the midst of civil wars – and its spiritual essence thus undermined. Some have therefore come to conceive that the Islamic world is destined to collapse, and that Islamism is doomed to extinction. This is not because it is promoting an unattainable project – the ‘global Islamic caliphate’ – but because it is entirely based on a mythical idea that is being reconstructed for purely political purposes, based on what has ever been a struggle for power, right from its very origins.

[1] The term Umm al-Kitāb (‘Mother of the Book’), taken from Qur’ān XLIII (al-Zukhruf), 4 and XIII (al-Ra‘d), 39 is held to be the original Qur’ān preserved on a ‘well-guarded tablet’. See Glossary: Preserved Tablet. (Ed.)

[2] The book Les trois visages du Coran (Partie 2 La genèse des Ecritures) by Leila Qadr is downloadable from the Almuslih Library here.

[3] For this see the following Almuslih Libraries: The Main Catalogue section The Constituents of the Qur’ān and Early non-Muslim historical sources.