The critical study of the Qur’ānic text in the West began with a work that is still today a work of reference: Theodore Nöldeke’s The History of the Qur’ān,[1] published in 1860 and updated in 1909 by Friedrich Schwally.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

ALONGSIDE THE current of historical criticism of the Qur’ān, a new direction of research emerged around the middle of the twentieth century, which focused on the study of the literary genres employed in Islam’s sacred text. Once again, it was the German school that first paved the way in this new trend. The first of the series of articles in the journal The Muslim World in 1950 was entitled The Qur’ān as a Book, and included J. Wansbrough’s contribution with his Qur’ānic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation,[2] in which he studied patterns of Qur’ānic discourse and likened them to Jewish traditions. The discovery of a solidly structured discourse already indicates that it was a continuation of the ancient biblical tradition. The text of the Qur’ān thus appears less and less as an act of improvisation from the desert, but rather as a continuation of an exalted tradition.

The book The Original Qur’ān: The True History of the Revealed Text

In this work Mondher Sfar proceeds from the thesis of the Islamic narrative that holds the Qur’ān to be the sacred and literal word of God. It was literally revealed to the Prophet through the dictation of the angel Gabriel. For this reason it was not marred by any possibility of error. The Islamic narrative holds that the Qur’ān is the infallible word of God.

Mondher Sfar wonders whether the early history of Islam and the early Companions’ dealings with the Qur’ān actually support this thesis, or in some way contradict it. He concludes by saying that there is no reliable historical or theological basis that unequivocally supports the Islamic narrative, but that what is given in the Qur’ān to be the inspired text should not be equated with ‘the original text of the heavenly Qur’ān, which is God Himself alone.’

The researcher observed how the first generation of Companions dealt with a number of readings and ways of handling the Text during the lifetime of the Prophet and shortly after his death, and established that the presence of differing texts existing during the life of the Prophet helps to explain why these differences were accepted. It was because the early Muslims saw the Qur’ān as a copy of the ‘original heavenly Qur’ān’ but not something in itself equating to it or attaining to it. This was due to its being subject to the vicissitudes of Muḥammad’s life, the environment of the time and the capacity of humans with their levels of cognitive perception to understand its meanings and connotations. Later, for reasons dictated by social and political circumstances, Muḥammad’s revelation came to be transformed into the ‘infallible Word of God’, and thus it became absolutely forbidden to deviate from it, even one iota.

The early Muslims saw the Qur’ān as a copy of the ‘original heavenly Qur’ān’ but not something in itself equating to it or attaining to it

According to the Islamic narrative and tradition, it is well established that questioning the authenticity of the Qur’ānic text is blasphemous, an act of sacrilege in particular against one of the main fundamental, if not the most important, beliefs of Islam after faith in God and His Messenger. Mondher Sfar consideres that this taboo – which surrounds the question of the history of the Qur’ān – has no theological justification in the revealed Text, not does it have even a historical justification, since the Islamic tradition itself includes a mass of information on the problems associated with the transmission of the Qur’ān prior to its reaching us. In this regard, the researcher went on to say the following:

The most surprising fact about this tense attitude of Islamic orthodoxy is that it stands at odds with the same doctrine formulated by the Qur’ān about its own authenticity. In fact, far from claiming any textual authenticity, the Qur’ān offers a theory of revelation that strongly refutes such a claim. This Qur’ānic doctrine explains that the inspired Text is nought but a product of the original, authentic Text found on the divinely preserved Heavenly Tablet[3] that ordinary humans cannot access. In short, the true Qur’ān is not the one that was revealed, but the one that remains in heaven in God’s hands, and this is the only true witness of the revealed Text. In short, the Qur’ān does not attribute authenticity to the Text revealed to Muḥammad, but only to the original Text preserved by God

The researcher proceeds along the same path, arguing that the transition from the heavenly Original to the version sent down that uses human language, explains how in one way or another, these possibly do not match. Note – according to the researcher – that the Prophet did not receive the revelation by the way of a literal dictation, but by way of inspiration. Moreover, the inspired text was subject to the law of divine reproduction, modification and revision. Thus, the revealed Qur’ān is neither eternal nor absolute, as the changes that took place indicate its historicity and its subjectivity to relative circumstance. There are also other factors that distinguish it from the original heavenly Text, including, according to the researcher, that

God commands Satan to reveal false verses through the mouth of Muḥammad, and then denounces them, and the Prophet is subject to some human deficiencies and short-sightedness, all of this is according to the revealed Qur’ān.

Therefore, Mondher Sfar considers it important to highlight the problem of the inauthenticity of the inspired Text and its correspondence letter-by-letter with the Qur’ān preserved on the Tablet.

Suggested Reading

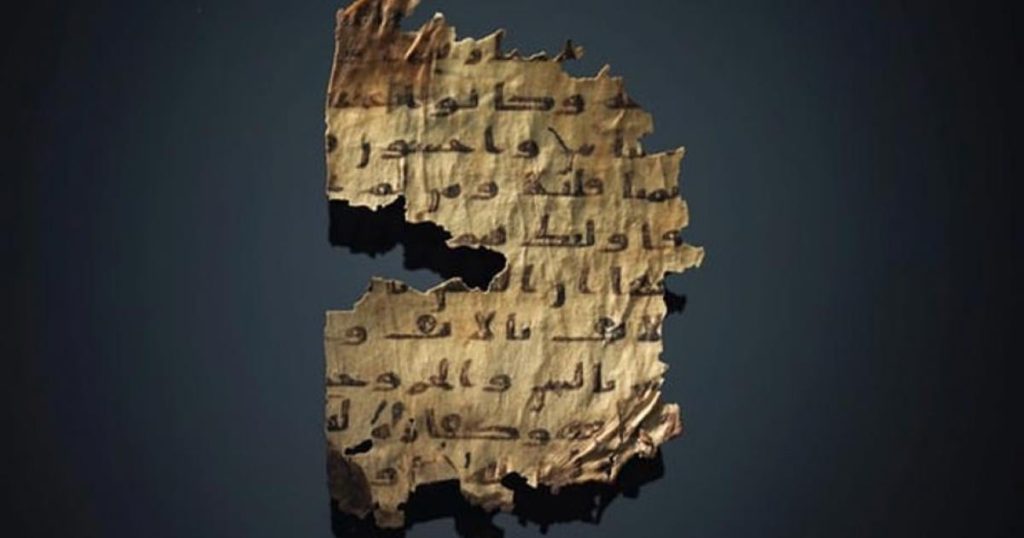

In defense of this proposition and basing himself on it, the researcher addresses the issue of the collection and codification of the Qur’ān during the early period. He says that at the death of the Prophet, the Text of the revelation was recorded on several media: manuscripts, shoulder bones, fragments, and other ephemera. The idea of grouping these scattered texts into a single collection was clearly a late innovation, something unknown to Muḥammad, and alien to the spirit of the Qur’ān. Only an arrangement of textual segments appeared during Muḥammad’s lifetime. These segments gave birth to the current sūras in a process that has yet to be understood, but is partly indicated by the obscure letters that open particular sūras – meaning the ḥurūf muqaṭṭa‘a (‘the disjoined letters’).[4]

The Islamic narrative created the myth of the angel Gabriel meeting the Prophet Muḥammad annually to review the texts

The Islamic narrative asserts that the first collection of the Qur’ān was carried out by the first caliph, Abu Bakr. The last collection process was carried out during the reign of the third caliph ‘Uthmān. But what do these two collation processes consist of? Opinions differ on this and we have not received anything definitive and certain in this regard. The situation is ambiguous as there is another process indicating intervention by al-Ḥajjāj.[5]

The researcher concludes by saying:

Regardless of the contradictions and ambiguities contained in the Islamic narrative about the history of the Qur’ānic text, it is clear that the creation of an official text of the Qur’ān was the culmination of a long process whose methods can be deduced only approximately and with great caution from the narrations and stories that have come down to us. The first generations of Muslims did not have an official Qur’ānic reference text on which consensus could be reached. To compensate for this, given the many problems it was causing, the Islamic narrative created the myth of the angel Gabriel meeting the Prophet Muḥammad annually to review the texts revealed during the previous year, repeating the process on two occasions in the last year of the Prophet’s life. Thus, according to the Islamic narrative, it was upon the death of the Prophet that the Qur’ānic text found itself codified, arranged and completed according to the divine will, while the processes that took place subsequently, according to many accounts, did not bring anything new. Only corrections were undertaken to the modifications that took place during these first decades of Islam. This is the mythological orthodox doctrine on the authenticity and frequency of the transmission of the inspired Text.

[1] See Nöldeke’s work in the Almuslih Library here.

[2] See this work in the Almuslih Library here.

[4] On these letters see the Almuslih article: The Qur’ānic text – Hypothesis 2.

[5] On this see the Almuslih article: When did Islam emerge? – 3.