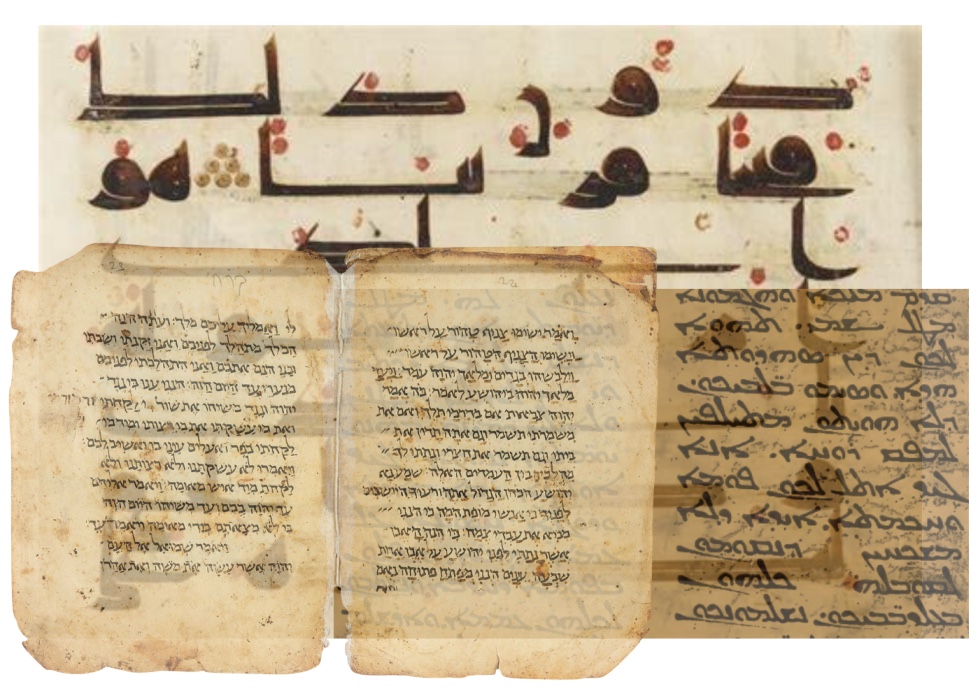

The Qur’ān is an ancient text, more difficult to decipher than the books of the Old and New Testament, because it lacks diacritics to indicate vowels and distinguish between some consonants. It also does not contain punctuation marks to identify the end of sentences. To decode them it is therefore necessary to apply some advanced methods of linguistics.

BY JADOU JIBRIL

JUST AS WITH the Biblical text, the Qur’ān includes many phrases such as ‘Praise be to God’, and supplications, poems, rhymed prose, wisdom and ethics, laws and commandments. The Biblical characters in the Qur’ān are mentioned in a allusive form, without any context or details being given. This suggests that they were intended for an audience that was already familiar with the Bible stories through oral transmission, and that therefore there was no need to flesh out these characters in detail. Merely referring to them was enough.

The text of the Qur’ān is characterised by a multitude of repetitions and sentences that are detached from their context. This proves beyond any doubt, according to some, that the text was not adopted as such all at once but went through many stages of writing, editing and recording by editors from various tendencies. Over the centuries, those who compiled the writings attempted to discern a thematic or chronological order for the Qur’ānic sūras, but to no avail. They were unable to classify the sūras according to the date they were written down, and so they artificially placed them in the maṣḥaf codex according to their length, starting from the longest and ending with the shortest. We notice readily that Paul’s fourteen epistles in the New Testament were arranged in exactly this order, from the longest to the shortest.

Is it a coincidence that the Mishnah in the Talmud and the prophetic books in the Bible are also organized this way? What can we conclude from a phenomenon such as this which we find in many contemporary manuscripts of different religions? Having difficulty determining any temporal sequence, the compilers therefore decided to place the longest texts, which seemed to them artificially the most important, at the beginning of the manuscripts.

The fundamental question facing the historian is: who wrote the text of the Qur’ān, and when?

The fundamental question facing the historian is: who wrote the text of the Qur’ān, and when? It is necessary to approach this issue with the same critical rigour that is applied to all ancient texts. The Qur’ān itself provides no evidence in this respect . There is clearly no mention there of historical events. There is no reference made to the Byzantine Empire, and these can only be found through searching for antiquities. The Persian Sassanid Empire and the Arabic kingdoms are also never mentioned, nor are the Jewish and Christian kingdoms that long existed in the southern Arabian Peninsula. Yet it is possible that these kingdoms exerted an influence over the people of the Hijaz because of the trade caravans that crossed the peninsula.

In fact, the historian is confronted with a text entirely devoid of context and detached from a historical framework. This makes it difficult to approach the Qur’ānic text with any historiographical approach. One has to set aside any later interpretations and examine the text independently of theories provided by the hadith and by traditions. The first written elements of the Qur’ānic text were in Syriac / Aramaic or in Greek, which were then translated into Arabic. The presence of Biblical characters in the text suggests that the Qur’ān may be a paraphrase of Biblical narratives, as is the case with some Dead Sea Scrolls of the Pesharim category.[1] However, the central status of Mary and Jesus in entire sūras indicates that this text is an unorthodox Christian product – a heretical text – linked to Monophysite currents concerning the human nature of Jesus and to the doctrine of Docetism that questioned the crucifixion.

The audience addressed in this text consisted mainly of Syriac and Greek-speaking Christians, descendants of the Aramean and Assyrian populations. The Judaeo-Christian sects might be the Nazarenes (Naṣārā in the Qur’ān), the Ebionites and the Elkesaites,[2] who consider themselves neither Christians nor Jews.[3] These communities were Messianic Jews faithful to some of the practices of the Torah. In the eyes of the Christian Orthodoxy established in the Councils of Constantinople (381 and 553 AD), they were considered heretics or dissidents who rejected the divinity of Jesus, the principle of the Trinity and the crucifixion. They claimed to belong to the figure of James, Jesus’ brother, to his family heritage and possibly to the author of the Book of Revelation.

Suggested Reading

The early history of Islam – Introduction to the problems – 1

If the first original codification of the Qur’ānic text was not made in the Arabic language, we need to know who the authors of the Islamic traditions, the Sira and Hadith were, and to whom the Islamic religion owes its origin. None of these authors were born in the Arabian Peninsula or in the lands of the Byzantine Empire, but in the Khorasan, Bukhara, and Tabriz regions of Zoroastrian Iran (that is, present-day Uzbekistan and Afghanistan). They created a character called Muḥammad from these traditions, and established the details of his life some two hundred and fifty years after he lived.

The central status of Mary and Jesus in entire sūras indicates that this text is an unorthodox Christian product

Conclusion

Although Muḥammad was undoubtedly a historical figure in the early seventh century, none of these theologians could know anything concrete about his character. Even so, we have much more knowledge about a historical Muḥammad than we do about Jesus, other than his crucifixion by the Romans.

But it is important to keep in mind that the scholars do not unanimously agree on the dates for when the Qur’ān was written down. Some of the dates given commonly fall between the supposed era of Muḥammad (622–632), the reign of the Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān (644–656), the reign of Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān (685–705), and the ‘Abbāsid period in Damascus (657–750). Other scholars postpone the final writing of the Qur’ān to the ‘Abbāsid state at Baghdad (750-870) or even the tenth century. What distinguishes the collection of texts of the Qur’ān is the fact that each monarch who came to power in Damascus or Baghdad was keen to destroy previous versions of the narrative and create a new one that legitimized his authority.

In conclusion, the debate over the origin of the Qur’ān and its association with Islam is a complex one and is subject to diverse interpretations. Some scholars argue that the Qur’ān may be an unorthodox Christian work, while others support an origin that directly links it to Islam. The question remains open, and more research and studies are needed to deepen our understanding of the history of the Qur’ān and of Islam.

[1] The Pesharim ( פשרים ) texts are a group of interpretive commentaries on scripture.

[2] According to Early Christian and Manichaean sources, Elchasai or Elxai was the founder of the sect of the Elkesaites and the recipient of a book of revelation, the Book of Elxai. His is also said to be the belief followed by the parents of Mani. According to Epiphanius, Panarion 19, 2, 2, the name Elchasai means ‘Hidden Power’ (Aramaic: ḥail kesai). Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History (composed in mid- 3rd c AD) notes the following about the Arabian peninsula and the Elkesaites: “Once more in Arabia …other persons sprang up introducing a doctrine foreign to the truth, and saying that the human soul dies for a while in this present time, along with our bodies, at their death, and with them turns to corruption; but that hereafter, at the time of the resurrection, it will come to life again along with them…There has come just now a certain man who prides himself on being able to champion a godless and very impious opinion, of the Helkesaites, as it is called … It rejects some things from every Scripture; again, it has made use of texts from every part of the Old Testament and the Gospels…and it says to deny is a matter of indifference, and that the discreet man will on occasions of necessity deny with his mouth, but not in his heart. And they produce a certain book of which they say that it has fallen from heaven”. (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, Book VI, XXXVII-XXXVIII). The book, according to Epiphanius, condemned virginity and continence and made marriage obligatory. It also permitted the worship of cult images to escape persecution, provided the act was merely an external one, disavowed in the heart. Prayer was to be made always towards Jerusalem. (Ed.)

[3] Robert Kerr, in his work Islam, Arabs and the Hijra, advances the interesting theory that the term Naṣārā is the source of the Arabic term Anṣār which, though translated as ‘helpers’, actually has no etymological pedigree in the Semitic languages. This would mean that the Anṣār were Nazarenes, a sub-group of which – the Ebionites – were considered by Greek Christians to be Jews who adhered to Jewish law but who also believed in Christ (in an anti-Trinitarian sense) and the virgin birth. They recognised but one Gospel – Matthew – and it is this that is referred to in the Qur’ān as the Injīl. Kerr argues that the muhājirūn (‘migrants’) were Arabs while the Anṣār were Semitic anti-trinitarian Christians, and are referred to together in Qur’ān IX (al-Tawba), 100: And the first to lead the way, of the Muhajirin and the Ansar, and those who followed them in goodness – Allah is well pleased with them and they are well pleased with Him, and He hath made ready for them Gardens underneath which rivers flow, wherein they will abide for ever. That is the supreme triumph. Robert Kerr’s argument is available in the Almuslih Library here. (Ed.)

Read Part One of this essay here