One of the misconceptions that has prevailed for many decades in the countries of North Africa and the Middle East and entered the school and permeated the media, is the idea that the flourishing of the exact sciences in Islamic civilization during the first four centuries of Islam’s history was due to the adoption of religion as the comprehensive reference for society. Famous Muslim scientists who excelled in mathematics, physics and astronomy are to have succeeded thanks to the Islamic faith being their point of departure.

BY AHMAD ASID

THE FACT IS that this idea was simply an ideological position adopted for religious propaganda purposes. It bears no relation to the actual reality of this period. It did not lead to the renaissance of science in these countries so much as accelerate the spread of external displays of religiosity along with many superstitious and irrational ideas. And this is not to mention the promotion of political ideas aimed at theocratic tyranny and anti-development.

This process took place during the decades when the West was achieving glorious advances in the fields of specialized sciences, and when it increased its power, leadership and domination over the world thanks to its scientific, technological and military superiority. It occurred due to the strength of its political and social systems that were based on democracy, on wealth distribution and on respect for human rights, the foundations for which were completely lacking in the Islamic world.

The legal sciences were preferred, as ‘useful both for this world and the Hereafter’

As for the reality of science during the first four centuries of the history of Islamic civilization, it may be very briefly summed up as follows:

The Islamic civilization has known two different and distinct systems of scholarship that are not interrelated: the first of these is the field of ‘legal sciences’ represented in Qur’ānic readings, scriptural commentaries (tafsīr), the ḥadīth, fiqh (jurisprudence), uṣūl al-fiqh (principles of Jurisprudence), kalām scholasticism and Arabic philology. These are the ‘authentic’ fields of knowledge sprouting from the very soil of Islamic society and all of them revolving around the texts of the Qur’ān and the ḥadīth as the two primary sources for these sciences. They were also associated with how an Islamic society was to be managed given that the Caliphate State was a religious state based on the application of religious laws to its directing of its various affairs.

The second is the field of ‘rational sciences’ or ‘philosophical sciences’ and it includes mathematics, logic, geometry, medicine, physics, astronomy, theology or metaphysics, all of which were translated into the Islamic world from Syriac, Greek, and Latin sources.

The first field was the domain of religious scholars who specialised in it; these included Mālik ibn Anas, Abū Ḥanīfa, Ibn Ḥanbal, al-Shāfi‘ī and the jurist scholars who followed their methodology and doctrines. In the second field were philosophers, rational thinkers and scientists of the exact sciences, including al-Kindī, Ibn Sīna, al-Khwārizmī, Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, Ibn al-Haytham, al-Rāzī and others. These combined sciences were taught in many Islamic universities such as Al-Qarawiyyīn, Al-Azhar and Zaytūna, which explains why all of the philosophers and scientists were widely familiar with the aforementioned legal sciences – an example being Ibn Rushd (a chief magistrate). In the same way some jurist scholars, such as al-Ghazālī, were acquainted with the rational sciences, although they adopted a negative attitude toward them.

Nevertheless, the legal sciences pre-empted the other sciences in terms of indoctrination and acquisition, since memorisation of the Qur’ān and the study of its various readings and other aspects began in childhood while many students only came to the rational sciences many years later in life. Indeed, most of these ended up dispensing with them because the normative distinction between the two fields of scholarship led to a focus on the religious field and the abandonment of the rational field. This is because the former was considered ‘useful both for this world and the Hereafter’ and earns ‘a great reward from Allah’, while the second was considered to be purely material sciences that were of no use in the Hereafter, there being thus no reward in pursuing them. Some jurists even vilified and attacked them vigorously.

These two fields of scholarship worked out two theoretical approaches that were entirely different: one was the transmission approach that based itself on religious texts and their interpretation and worked to apply them to current conditions. This was the approach of the jurists which relied on deriving rulings by means of the ‘legal analogy’, a process of tracing back the ramifying branch to its ultimate original (the religious text), a process in which truth is always predetermined.

Suggested Reading

Loss of causality – a factor in the decline of Muslim science

The second approach is the rational approach, one which adopted the methodology of proof, logical deduction, comparison, observation and experiment in the study of natural phenomena and the observation of astronomical phenomena. It dealt with abstract ideas, including metaphysics, the ‘knowledge of the Craftsman’ in the words of Muslim philosophers. The legal sciences looked on reason merely as a tool for understanding, interpreting and applying religious texts, while philosophers, scientists, and thinkers considered it to be a method for questioning, researching and uncovering hidden truths.

One of the most important manifestations of the conflict between these two approaches is the concept of ‘causality’, whereby scientists and philosophers considered that the universe was subject to a causal chain in which the same causes always lead to the same results, the study enabling precise, scientific knowledge. The jurists, however, denied causality as an independent system, and clung to the religious interpretation of the Divine Will, one that intervenes in all the minutiae of the world.

The exact sciences were not an Islamic invention nor were they based on religious faith or the religious texts

If the first field gained political authority by virtue of its association with the state’s policies in conducting the affairs of an Islamic society, the second field was looked on as a foreign category that did not enjoy any similar protection or political legitimation. Accordingly the jurists worked alongside the Sultan in their capacity as ‘those who dissolve and bind’[1] and their numbers multiplied. Philosophers and scientists, on the other hand, worked on the sidelines of the official establishment, and were a very limited élite. This explains the persecution of all those who worked in the field of the rational sciences, as well as the authority which the religious scholars wielded, something which afforded them the possibility of trying philosophers and other thinkers, accusing them of heresy, atheism and disbelief, and enabled them to incite the public and the mobs against them, or even at times have their books burnt.

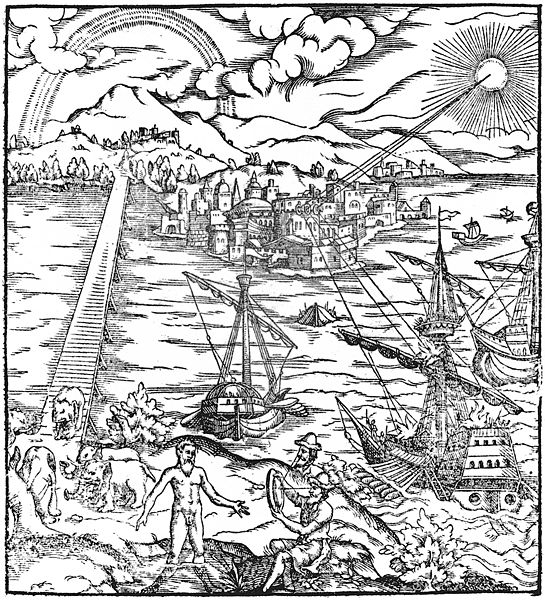

We may conclude from all of the above the following: the exact sciences were not an Islamic invention nor were they based on religious faith or the religious texts. These sciences were carried over from pre-Islamic civilisations into the Arabic language, starting from the middle of the second century AH. Muslim scholars excelled in these sciences and added new discoveries to them, but they nevertheless remained loyal to their early teachers such as Hippocrates and Galen in medicine, Pythagoras in mathematics, Euclid in geometry, and so on. This is why these Muslim scholars were always viewed as preoccupied with a field of science that was ‘foreign’ to the Islamic soil. The results of their research were therefore severely undervalued by the jurists and subjected to attacks. This accelerated the pace of their oblivion and neglect following the first four centuries, only to become in Europe a centuries-long fundamental reference.

Suggested Reading

The Natural Sciences – Between Religion and Religious Thought

This was the very same time that Muslims neglected them and embraced the legal sciences so that the number of jurists multiplied and popularised their transmission approach by imitating what went before, decorating them with marginalia and ‘texts’, initiating thereby the countdown to decline due to this self-isolation and closing off from the world – until western artillery arrived to awaken Muslims from their slumber during their imperialist colonial campaigns.

If, in the past, Muslims squeezed out the rational sciences and considered them something foreign to them – despite their essential universal application – in our own time, instead of making the necessary critical conclusions, they have simply gone back to searching in the religious texts for the scientific theories discovered by the West, considering there to be a ‘scientific miracle in the Qur’ān’.

They have thus missed their appointment with history twice, both in the past and now in the present.

[1] The term ahl al-ḥall wal-‘aqd is a phrase constructed from two complementary concepts, where ḥall denotes the act of ‘dissolving’ or freeing from obligations or ties, while ‘aqd conveys the establishment or binding of relationships. This duality reflected the dynamics of authority in governance and communal decision-making.

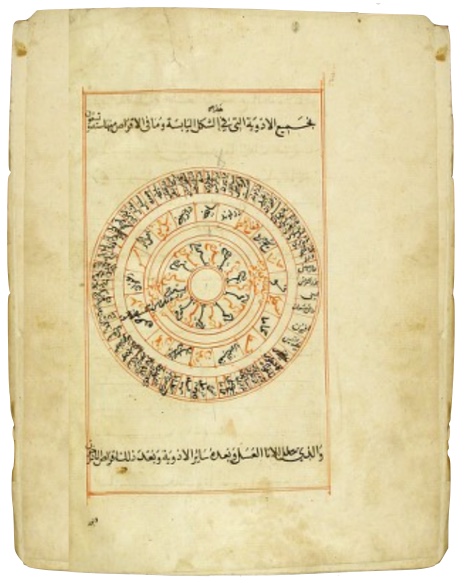

Main image: كتاب الترياق Kitāb al-Taryāq – Arabic translation of The Book of the Theriac (Η θηριακή), a medical composition by the Greek physician Galen (131-201 AD) in a 16th century manuscript.