Some citizens wonder why the jurisprudential system was unable to comprehend the curricula of science in the lands of Islam. We shall here look at the issue of causality in Islamic thought as treated by jurists and philosophers, since this constitutes the central problem and answers the question. It allows us to grasp the general conceptions on existence and on phenomena as understood by both sides.

BY AHMAD ASID

MUSLIMS, AS WE KNOW, received what we term the intellectual sciences via translations, within the framework of a general and comprehensive intellectual, philosophical ontological system. It is therefore not possible to understand them in isolation from their roots. This is evidenced by two things:

1. Many religious scholars – including al-Ghazālī and Ibn Taymiyya – made an attempt to pay attention to these sciences but did not succeed and did not contribute anything to them

2. All those who actually worked in these sciences and specialised in them became the object of suspicion and viewed as advocates of atheism and heresy, and operating in a ‘foreign’ intellectual structure.

This explains the standard trade-off adopted by jurists between the ‘honourable sciences’ that are useful for the Hereafter, and ‘mundane sciences of no benefit’ for the Hereafter. This was due to their failure to separate those sciences from their Greek intellectual framework.

To illustrate this we may cite the intellectual debate that ancient Islamic thought witnessed between philosophers, jurists, the Mu‘tazila[1] and Ash‘arī[2] theologians concerning the principle of ‘causality’, which philosophers considered to form the basis of the natural sciences. The term ‘causality’ refers the intellectual principle of logic on which the mind depends to grasp the absence of arbitrariness in natural events, and their subjection to fixed laws of necessity, and by which the same causes always lead to the same results.

Muslim jurists held that science consisted in knowing what was in the religious texts and seeking to apply it

Science aims to uncover these laws and refine them through experimental research and calculate them mathematically, translating the law of nature into an abstract law. This process is not possible without a realisation that natural and astronomical phenomena all occur as a result of the existence of reasons for their occurrence. This allows them to be predicted scientifically on the basis of precise calculations that prove the solidity of the system of the universe, and it permits a correspondence between the system of nature and the system of reason.

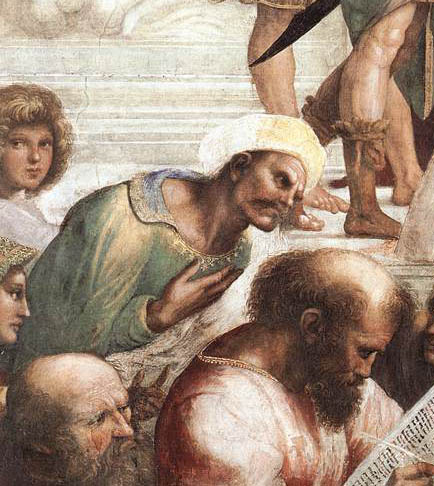

Ibn Rushd described this system in his work Al-Kashf ‘an Manāhij al-Adilla (‘On Discovering the Methodologies of Proofs’) which criticised the jurists and the theologians who denied this system:

It is important that we understand that anyone who denies the existence of causes that influence – with God’s permission – their manifestations has invalidated wisdom and science itself, since science is the knowledge of things with their causes, and to express denial of causes altogether is something alien to human nature.

He then adds a criticism of al-Ghazālī:

As for anyone who denies that causes exhibit a chain of causal factors in this world, has thereby denied the great and sublime, the wise and almighty Craftsman Allah.

That is, whoever denies the causal relationship between phenomena has denied the existence of God because He is the one who developed this wonderful system of the universe. In this way Ibn Rushd championed science and religion both together, since he considered that religious faith should be based on science and intellectual evidence.

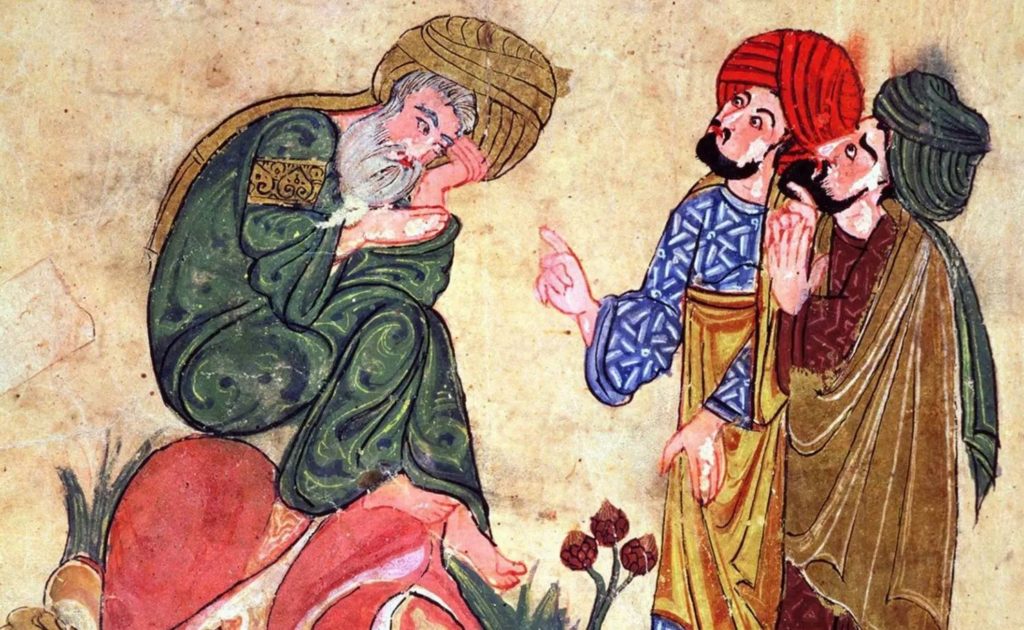

Al-Ghazālī and Ash‘arī jurists objected to the principle of causality, on the grounds that saying that there were ‘necessary reasons’ meant limiting the divine will. For al-Ghazālī:

To associate what is habitually believed to be a cause with what is believed to be the effect is not necessary for us. Indeed, in the case of two things, neither of which is the other and where neither the affirmation nor the negation of the one entails the affirmation or the negation of the other, the existence or non-existence of the one does not necessitate the existence or non-existence of the other. For example: the quenching of thirst and drinking, satiety and eating, burning and contact with fire, light and the rising of the sun, death and decapitation, healing and the consumption of a medicine, diarrhea and the use of laxatives, and so on.

Satiety for al-Ghazālī is not the result of eating and burning up is not due to fire – that is, there is no necessary relationship between a cause and its effect but instead may or may not occur according to the divine will. For the action is a divine action because God intervenes in all the minutiae of the world. According to al-Ghazālī’s logic severing the neck of a person does not necessarily result in death, for death only takes place by the will of God.

Those who argue for the ‘permissibility’ – not necessity – that phenomena occur are simply championing the miraculous

The jurists brought as evidence the miracles of the prophets such as the failure of the Prophet Abraham to be consumed by fire, which became a coolness and peace for him as stated in the Qur’ān.[3] Thus burning is not caused by the action of fire, but by a divine act, and if we were to say that there is a causal relationship between fire and burning, this might lead us to deny miracles and thus defy God’s ability and absolute will.[4]

Suggested Reading

Scientific knowledge then, according to Ibn Rushd, is impossible without this principle of causality, and whoever denies or rejects this principle cannot research scientifically into phenomena and understand them knowledgeably and scientifically. To invalidate causality is to invalidate the ‘divine wisdom’ and the ‘divine law’. Jurists, however, rejected this logic and held that science consisted in knowing what was in the religious texts and seeking to apply it. Those who argue for the ‘permissibility’ that phenomena occur, and not their necessity, are simply championing the miraculous and the supernatural over against the solidity of the system of the universe.

This is one of the many reasons why science did not receive the required attention after the fourth century AH, that is, after the period of al-Ghazālī. This is reflected in the general trajectory of Islamic society, and has led to according absolute priority to metaphysical interpretations over scientific research and rational thinking. It has led, among other things, to a devaluation of the intellect and to considering it something in itself deficient, weak and incapable of discovering new knowledge.

[1] The rationalist Mu‘tazila school was an Islamic school of speculative theology which flourished in the cities of Basra and Baghdad during the 8th–10th centuries (Ed.)

[2] Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ash‘arī defected from the Mu’tazila and formed the Ash‘arī school which adopted an anti-Mu‘tazila position and supported the prioritisation of naql over ‘aql – uncritical imitation over the operation of reason. The views of the Ash’arite school were rooted in the dogma of ‘occasionalism’ which holds that rather than created objects having inherent existence, Allah constantly recreates each atom anew at every moment according to his arbitrary will. The effect of this was to undermine the basis for what the contemporary world understands as natural laws. (Ed.)

[3] Qur’ān XXI (al-Anbiyā’), 68-69: They cried: Burn him and stand by your gods, if ye will be doing. We said: O fire, be coolness and peace for Abraham. Scholars note that the incident of Abraham being saved from the fire depends on a Qur’ānic use of a mistranslated passage from Genesis, XV,7: God called Abraham out of Ur of the Chaldees – ‘Ur’ being the Babylonian term for ‘city’. The confusion came about because a 1st century AD Jewish rabbi named Jonathan ben Uzziel read the term ‘Ur’ as if this were a Hebrew word: ֵאוּר (ōr) meaning ‘fire’. So the phrase מֵאוּר כַּשְׂדִּים (‘from Ur of the Chasdīm’) circulated as being ‘from the fire of the Chaldees’ – the version that was later to be picked up by Muḥammad (Ed.)

[4] For a discussion on the position of al-Ghazālī on ‘natural philosophy’ and the necessity of causes see our Model Curriculum, Part II The Route to Knowledge, pp.27, 32-33 (Ed.)