There is a question that takes priority over all other questions, and this is the isnād – the ‘train of transmission’ of hadith – an axiom taken for granted, ratified in heritage, and handled without questioning. The author ‘Alī al-Dayrī investigates the reasons for the emergence of isnād andhow it was invested in “as an ideology of power – as a form of institution and discourse for a state, a caliphate and powerful groups for their control, as a view of history, and a justification for the conflicts between warring groups – in that it expressed the will for power, for truth, and for domination.”

MORE THAN A TOOL for the transmission of hadiths, the isnād informed history, politics and power. ‘Alī al-Dayrī’s work The Best of Centuries: How should we understand history? seeks to uncover the background behind the rise of the isnād and its pervasive presence, its transformation into a firmly-rooted practice for the recording of the hadiths, reports, records and history of the first three centuries, and how the authorities were able to promote their prototypes, embrace them and exploit them. He investigates the position that the isnād occupied in the traditional heritage, becoming a pivotal criterion for how one does, or does not, rely on reports or ancient records.

But the scope of the isnad expanded beyond that of a handed-down traditional record to become a tool of politics, as al-Dayrī explains:

It was not a pure science of politics, but something brought about by politics, disputes and conflicts. We know that when politics enters any field of knowledge it taints it with tendentiousness and fanaticism, and the arbitrariness of power the will take over it. The science is in the hands of those wielding power and authority, the authority to decide what is and what is not ‘true’, what constitutes a part of the Sunna and what does not, what is to be considered ‘reliable’ and what is ‘weak’, and what does or does not constitute an authoritative religious text.

Al-Dayrī’s work reveals the organic link between the ‘best of the centuries’ concept and the isnād, how this isnād itself came up with the idea of ‘the best of centuries’ and how this phrase by means of isnād

closed off the possibility of reading history according to its actual conflict-ridden context conflicts, because it turns history into a sacralised doctrine wherein you are only allowed to see Good. History thus becomes a constant contest between Good and Evil. By expelling Evil from ‘the best of centuries’ they are made into sanctified – not historical – centuries. The ‘best of centuries’ and the isnād are both of them ideologies concocted by the authorities. They were an essential component in the elaboration of the religious sciences and invested in to subsequently either remove or preserve the religious legitimacy of a caliphate. The concept of ‘the best of centuries’ was one the products of this isnād and through this, and its view on history and seditious discords, it became transformed into a doctrine by which the faith of others could be judged.

“How can anyone rely on an isnād process that is governed by ethnic, sectarian and provincial biases?” he asks.

The emergence and development of isnād forms a core pillar of the traditional religious sciences. In this development Imam al-Shāfi‘ī (150-204 AH) played a pivotal role by constructing a religious identity for isnād. It would not have been possible for isnād to occupy such a privileged place in the heritage without al-Shāfi‘ī’s role in bestowing religious legitimacy upon it and establishing the authoritativeness of the khabar wāḥid – the ‘relation by a single individual’, for the reliance upon it as a basic criterion for the acceptance of a hadith, and for its use in the process of jurisprudential deduction.

Were it not for the widespread employment of the khabar wāḥid the authority of the Qur’ān itself would not have been so shut out

Ever since al-Shāfi‘ī the most important research topic in the uṣūl al-fiqh (‘the principles of jurisprudence’) and one widely employed in jurisprudence, is this khabar wāḥid relation. This is the most prolific source for the jurisprudential deduction process and is the main foundation upon which the jurisprudential code is constructed and developed. Had it not been for the declaration of the khabar wāḥid as authoritative, and for the vertical and horizontal expansion by uṣūl al-fiqh scholars on the foundations laid by al-Shāfi‘ī, fiqh would not have expanded and assumed its taken on its inflated dimensions, atrophying and progressively diminishing other dimensions of the faith. Were it not for the widespread employment of the khabar wāḥid the authority of the Qur’ān itself would not have been so shut out and the evidences of most of its metaphysical, spiritual, moral and educational verses neglected.

Suggested Reading

Al-Shāfi‘ī’s was but one of the views on khabar wāḥid, but his opinion was decisive and excluded the views of the major scholars who were deliberately ignored by the fundamentalists, to the point that their existence was well-nigh forgotten. Al-Naẓẓām, among others, did not accept the authoritativeness of the khabar wāḥid, as Abū al-Ḥusayn al-Baṣrī reports in his work Al-Mu‘tamad fī Uṣūl al-Fiqh:

Most people say that it does not require verification, while others said that it does. Some of the Ẓāhirīs did not stipulate the need to compare views with related reports. Abū Isḥāq al-Naẓẓām laid down a condition for verification that it be compared with related reports. It is said that he stipulated this also for tawātur hadith.[1]

Al-Jāḥiẓ in his work Kitāb al-Akhbār also relates how Abū Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn Sayyār al-Naẓẓām said concerning the reports related on the Messenger of God:

How can the audience accept the truthfulness of a narrator if the report does not demand this of him, or there is no verification to indicate the truth of something that he was not present at, or no analogous testimony to confirm it, or that lying is to be ruled out in his case (despite the multiplicity of pretexts that people use to tell lies and the sophistication of their trickery)? If there were no ‘sincere ones’ who lied, or ‘honest ones’ who deceived or ‘reliable ones’ who forgot, or ‘loyal ones’ who betrayed – life would be sweet and one would be safe from any negative consequences.

In similar vein al-Māwardī writes:

Both the deaf and the privileged are to be disqualified as narrators of khabar wāḥid

Al-Naẓẓām’s refusal to accept qualification of the deaf and the privileged, among others, did not affect others using the khabar wāḥid narrations and accepting them as authoritative, as established by al-Shāfi‘ī. The position taken by the authorities to embrace his view, and the support for it among the kalām scholastics, the fundamentalists, the jurists, the interpreters and the hadith scholars has meant that his was the view that always prevailed and turned into a religiously legitimised authority that was denied to others. His works were circulated and adopted in religious educations, regardless of the correctness, rationality and coherence of his views.

[1] The tawātur hadith are those whose the narrators constitute a group or large number, on the understanding that it is considered impossible for them all to agree to transmit a lie. On the various categories of the hadith isnād see Glossary: ‘hadith’.

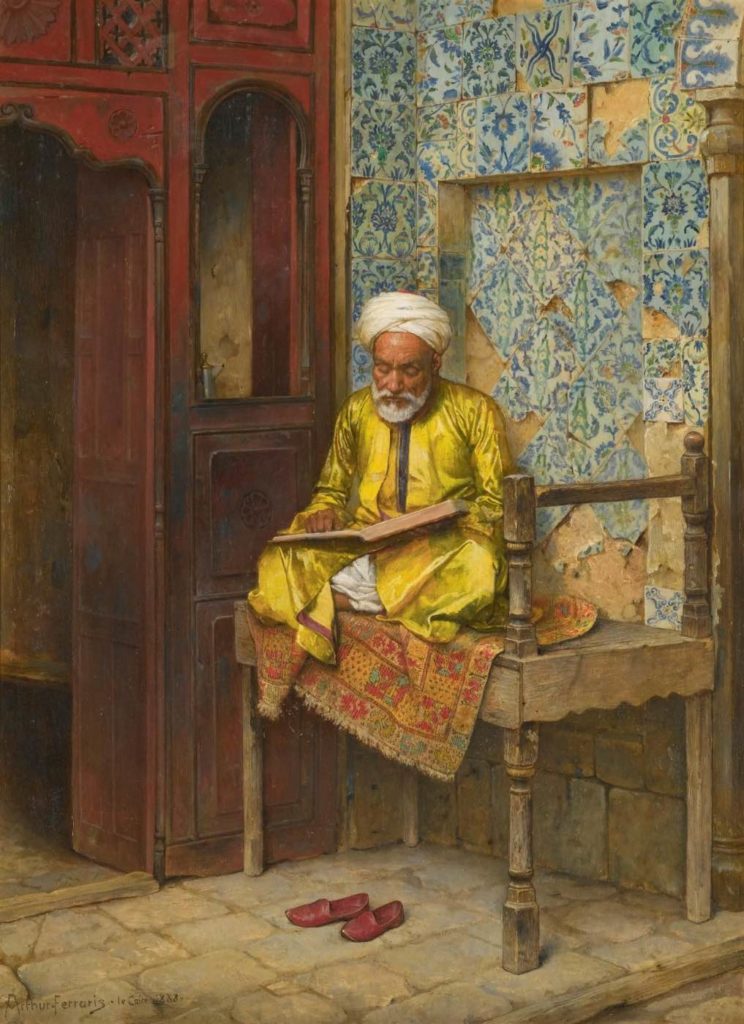

Main image: ‘The learned man of Cairo’ by Arthur Ferraris, 1888.

See Part One of this essay here