Before we get into the subject of the article, we should say that there is no agreement between Sunnīs and the Shī‘a on many narrations, the hadith included, and this is without entering into the interweaving doctrinal differences between the two sects, whereby each party claims that theirs is the true and correct opinion.

BY YUSUF YUSUF

THIS IS HARDLY SURPRISING, in that each call the other by opprobrious names: Sunnīs call the Shī‘a Rāfiḍīs. The Rāfiḍa group arose when a Yemeni Jew named ‘Abdullah ibn Saba’ declared his Islam and claimed to love the Ahl al-Bayt, the ‘people of the house’ (the family of the Prophet Muḥammad), and in his intense love for ‘Alī claimed that he had been the one recommended to succeed the Prophet,[1] and proceeded to raise him to the rank of divinity. In his work Al-Maqālāt wal-Firaq al-Qummī states:

He professed his status and held him to be the first to state the obligatoriness of ‘Alī’s imamate and his being denied this, and overtly impugned Abū Bakr, ‘Umar and ‘Uthmān and the rest of the Companions.[2]

As for the Shī‘a, these call the Sunnīs Nāṣibīs. These are considered enemies of Imam ‘Alī or the Ahl al-Bayt, who deny them any virtues, and are thus anti- Shī‘a. Shī‘a jurists went so far as to declare the Nāṣibīs ‘impure’ and are to be judged ‘infidels’: one may not give charity to them, nor contract marriages with them. [3] Some researchers believe that the phenomenon of naṣb (anti-‘Alid sentiment) originated with the killing of ‘Uthmān and developed further during the era of the Umayyads who used to issue insults from the pulpit against Imam ‘Alī. One of the most hare-line Nāṣibīs were Mu‘āwiya ibn Abī Sufyān and the Kharijites.[4] The Shī‘a have written books on naṣb and the Nāṣibīs, including the work Al-Shihāb al-Thāqib fī Bayān Ma‘nā al-Nāṣib by Yūsuf ibn Aḥmad al-Baḥrānī (1696-1755).

The Sunnīs and Shī‘a directed criticisms at each other regarding the authenticity of the Ṣaḥīḥ collections

Among both the among Sunnīs and the Shī‘a there are many ṣaḥīḥ collections of hadith (hadith that are considered strong and reliable) and I will mention just the most famous of them. Among the Sunnīs but the most commonly referenced are the six Ṣaḥīḥ books. As stated on the IslamWeb site:

The term ‘the Six Books’ refers to six works in the literature of hadith held to be the most accurate books written in this discipline. These books are: the Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Sunan al-Nasā‘ī, Sunan al-Tirmidhī, Sunan Abī Dawūd, and Sunan Ibn Mājah. As for the Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, the Muslim nation has universally accepted what they contain, with the exception of a few hadiths criticized in the work al-Ḥuffāẓ , a well-known record, and by al-Dāraquṭnī in his book Al-Tatabbu‘. As for the four ‘Sunan’ works, these also include some weak hadiths, and therefore to evaluate a hadith in these works requires one to trace their methodology and for experts in the field to judge them as fitting. Some scholars have done this.

The Shī‘a have four Ṣaḥīḥ collections, and of this one may cite the following:

The ‘Four Books’, or the ‘Four Uṣūl’, are the four hadith works that have gained a special place – after the Qur’ān. They are: Al-Kāfī (compiled by Thiqat al-Islām al-Kulaynī – ob. 941), Man lā Yaḥḍuruh al-Faqīh (‘He who has no Faqih on hand’ by Shaykh al-Ṣadūq – ob. 991), Tahdhīb al-Aḥkām (by Abū Ja‘far al-Ṭūsī – ob. 1067) and Al-Istibṣār (again by Abū Ja‘far al-Ṭūsī). The first to use the term ‘The Four Books’) was Zayn al-Dīn al-‘Āmilī, known as al-Shahīd al-Thānī, a descendant of al-Ḥillī, and thereafter the term began to be commonly used in jurisprudential texts. Some Shī‘a scholars regard all hadiths in ‘The Four Books’ to be reliable, but most of them restrict its reliable hadiths to those that are mutawātir[5] or have reliable chains of transmitters.[6]

Mutual criticism between the two denominations

Each party, the Sunnīs and the Shī‘a, criticize the other and holds their own Ṣaḥīḥ collections to be the more correct. The Shī‘a outright refuse to recognize any of the Sunnī Ṣaḥīḥ volumes in any way, and the Shī‘a website Markaz al-Abḥāth al-‘Aqā’idiyya has this to say on the matter:

The Shī‘a do not accept Bukhārī and Muslim and the six Ṣaḥīḥ collections. Every free Muslim wheresoever they be arenot to accept Bukhārī, Muslim and the six Ṣaḥīḥ collections as true, due to all the Isrā’īliyyāt[7] contained therein, or hadith that contain clear insults against the Messenger of God and the Prophets. For the Shī‘a there is no true book at all other than the noble Qur’ān. All books other than the Qur’ān are to be subjected to research as to their chains of transmission. The Shī‘a scholars first investigate their author, and then each of the hadith he relates, one by one. If the author is of correct belief, trustworthy and scrupulously truthful, the Shī‘a then take his work as a reference, but scrutinise each of the hadith he relates to see if the train of transmission is sound.

Many jurists stated that āḥād hadiths accounted for around 99 percent of the total of the hadiths

The Ahl al-Sunna wal-Jamā‘a[8] (the Sunnīs) also declared the same with regard to the four Ṣaḥīḥ collections of the Shī‘a. On the website Islam Question and Answer there is much material critical of them, which may be summarised as follows:

It may well be that in the books of the Shī‘a there are some authentic hadith, for example on the virtues of Ahl al-Bayt, but any validity that they have is determined by the Sunnī chains of transmission, not by the Shī‘a chains of transmission, nor by any reliance on their books. On this Ibn Taymiyya said: “As for the peculiarities of the Rāfiḍīs that demonstrate extreme ignorance and misguidance, we do not purpose to mention these here. But what is intended here is that every sect besides that of the Ahl al-Sunna wal-Ḥadīth that follow what the Prophet left behind do not really differ from other sects with respect to the truth, and the Rāfiḍīs are more eloquent in this respect than others… It is irrational for the Rāfiḍī Shī‘a to take a unique position on a ṣaḥīḥ hadith, because there must be conditions for the authenticity of a hadith, the most important of which being the just nature of its narrators and the precision of what they narrate.

Two points emerge from this:

Firstly – There are problems with the Sunnī Ṣaḥīḥ collections themselves, highlighted frequently by the commentators. The Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the foundational work itself, is doubted as to its authenticity. This is particularly the case due to the time gap between the Messenger (who died in 11 AH) and the compiler al-Bukhārī, who died in 256 AH. What is more, al-Bukhārī claimed that out of 600,000 hadiths he isolated a total of 7,275 hadiths, and that these, after Ibn Hajar’s addendum, come to a total of 2,761 hadiths. There are also hadiths that are insulting to the Prophet: examples being ‘the sorcery of the Prophet’, ‘the hadith of the wolf and the cow’s words’, and the Messenger’s attempt at suicide. The remaining four Sunan works – Sunan al-Nasā‘ī, Sunan al-Tirmidhī, Sunan Abī Dawūd, and Sunan Ibn Mājah –

include some weak hadiths. The evaluation of a hadith requires that it be traced back and for experts in the field to judge them as fitting.

Secondly, the Shī‘a sources indicated that all the Ṣaḥīḥ collections are dubious, and particularly the six Ṣaḥīḥcollections without exception. Such an admission is portentous:

“for the Shī‘a there is no true book at all other than the noble Qur’ān and all books other than the Qur’ān are to be subjected to research as to their chains of transmission”.

As far as I see it there is a problem in the four Ṣaḥīḥs of the Shī‘a as well, because these Ṣaḥīḥs were adopted as authoritative at a later stage: “

‘The Four Books’) was Zayn al-Dīn al-‘Āmilī, known as al-Shahīd al-Thānī, a descendant of al-Ḥillī, and thereafter the term began to be commonly used in jurisprudential texts”.

This leads us to another question: what were the Shī‘a adopting as authoritative before the tenth century AH – that is, before the adoption of these Ṣaḥīḥ collections by Zayn al-Dīn al-‘Āmilī?

We may conclude with the following points:

Specifically, the Sunnīs and Shī‘a directed criticisms at each other regarding the authenticity of the Ṣaḥīḥcollections on the grounds of their including hadiths that range from ‘sound’ to ‘good’ and ‘weak’ or other categories, or mutawātir hadith of several narrators reporting from several others about the Messenger, or hadith that are suspect or āḥād (related only by a single narrator) from several narrators reporting in turn from a single individual about the Messenger.

There is an interesting numerical difference between the hadiths of Abū Bakr (numbering 500) and the later hadiths composed in their thousands

Many jurists, including al-Suyūṭī, stated that most of hadiths are āḥād hadiths. In his work Al-Azhār al-Mutanāthira he made a comparative calculation of the totality of the hadiths that are not simply repetitions of each other, that is around 11,000 hadith, and that the percentage of mutawātir hadiths did not amount to more than 1 per cent while the percentage of suspect āḥād hadiths accounted for around 99 percent.

A convoluted problem exists with regard to both the ‘Four Books’ and ‘Six Books’ of the Ṣaḥīḥ collections, and that is the doubt about the entirety of them. This is because none of the hadiths were written down at the time they were spoken, that is, during the lifetime of the Messenger:

Abū Sa‘īd al-Khudrī reported that the Messenger of Allah said: “Do not write down anything from me, and he who wrote down anything from me except the Qur’an, he should erase it. But, narrate from me, for there is nothing wrong in doing so.”[9]

If we assume for the sake of argument that during the latter era of the Messenger the hadiths were written down, after the Messenger had gained power, the fact is that those who came after him – Abū Bakr and Omar – burned everything that had been written down.

Al-Dhahabī reported that Abū Bakr collected together the hadiths of the Prophet into a book and the number of these hadith totalled five hundred. He then called for fire to be brought and proceeded to burn them. What is odd is that is that Abū Bakr did not undertake this destruction on the basis of a legal text, but instead justified his action by saying that he destroyed them for fear that he might have written down something that he had not recalled properly.[10]

‘Umar did the same thing:

Abū Bakr first forbade the narration of the Sunna of the Messenger, then burned the written documents of the Sunna of the Messenger that he had with him; then ‘Umar collected the Sunna of the Messenger that had been written down by other people and the books that they had been keeping and burned them.[11]

Suggested Reading

Added to this are doubts concerning the interesting numerical difference between the hadiths of Abū Bakr (numbering 500 hadiths, which may be authentic due to his being the contemporary of the Messenger), and the later hadiths of the Ṣaḥīḥ collections which were composed in their thousands. On the basis of all this, I personally believe that most of the Ṣaḥīḥ collections were entirely made up by those who recorded them, as directed by the rulers of the time.

[1] On this see Glossary: ‘Shī‘a’.

[2] Extract from the website Madād.

[3] On this see Glossary: ‘Nāṣibī’.

[4] See Glossary on this group.

[5] A hadith whose narrators constitute a group or large number. For the categories of hadith reliability, see Glossary: ‘Hadith’.

[6] More information can be gained from the website WikiShia.

[7] In the field of hadith the term Isrā’īliyyāt (‘Israelisms’) refers to narratives assumed to have been taken over from earlier Jewish folklore. The term can also be extended to cover the genre of qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā’ (‘Tales of the Prophets’). Originally simply descriptive, the term Isrā’īliyyāt later took on a negative connotation, so that Muslim scholars forbade the transmission of hadith that were considered to be of such foreign origin, and associated them with pernicious intent. See also Almuslih article: The meaning of the term ‘Isra’iliyyat’.

[8] On this term for the Sunnīs see Glossary: ‘Ahl al-Sunna wal-Jamā‘a’.

[9] https://sunnah.com/muslim:3004

[10] Citation from the website: الحوزة الاعلامي also تذكرة الحفاظ للذهبي ( 1 / 5 ) وعلوم الحديث لصبحي الصالح, p. 39.

[11] Aḥmad Ḥusayn Ya‘qūb, الخليفة عمر يمنع رواية سنة الرسول on the website: الأشعاع الأسلامي .

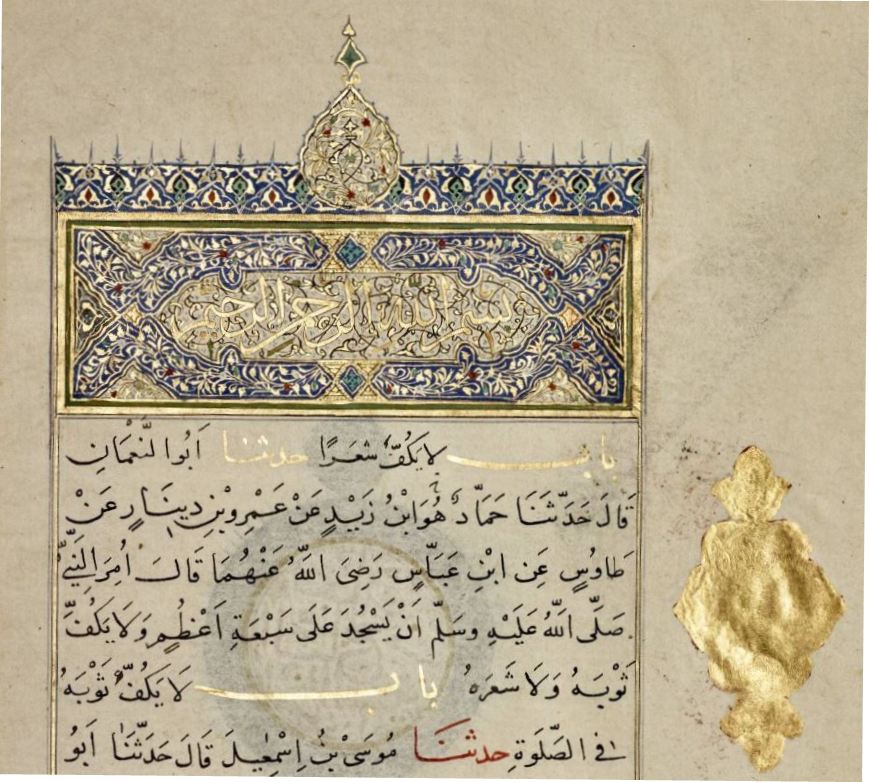

Main image: The ḥadīth considered as a text ranking with Qur’anic scripture: a muṣḥaf-like page from the Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī with gold illumination. The passages calligraphically inscribed are Ḥadīths 815 and 816 from chapter كتاب الأذان : “The Prophet was ordered to prostrate on seven bony parts and not to tuck up his clothes or hair” (when performing ṣalāh). Unknown artist, Shiraz, dated 1400-1450. From the Keir Collection of Islamic Art, Object number K.1.2014.800.1.