Every day, one becomes more convinced that the world today is being changed by science, knowledge, the means of communication and new technology, and by conflicts and the unexpected surprises of history. One also remains convinced that serious writing, bold ideas and vivid words can help awaken some minds from their slumber.[1]

IN A NEW PATTERN of human existence Man’s relationship with Man, with material things, with knowledge, truth, memory, time and place, with the past, present and the future are being refashioned in a way that changes the definition of concepts that have hitherto long been firmly established in human cultures. New ways are being birthed to apply justice, freedom, security, peace and other universal values in this renewed reality. Today, for example, information security is a new pre-requisite for security, which now expands from owning material things produced in earlier modes to the ownership of ideas in knowledge production.

Capital has now transformed from physical capital – fixed assets – to knowledge capital as represented in the fields of education, information, ideas, skills, projects, innovation, artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and the like. To reconstruct man’s connections with his surroundings means reconfiguring his mode of existence in the world. This new pattern of human presence invites us to understand the dynamics of change in the world, and how transformations of reality are no longer determined by traditional equations and factors, which are subject to constant change.

In the contemporary environment religion appears to be emerging out of its own sphere and coming to dominate other fields of life which are properly the domains of the mind, of science, knowledge and the accumulation of human experience. Religion is thus turning from being a solution to the spiritual and moral need to constituting a problem threatening the mind and preventing this accumulation of human experience. Many of the problems of the Islamic world are due to the failure to recognize the true sphere of religion and the limits of its mission in human life. The resulting domination of religion over other fields of life is causing disruption to the function of reason, scientific enquiry and knowledge acquisition, and encouraging the neglect of the value of the accumulation of human experience. It is having an inevitable impact on development.

Religion is turning from being a solution to spiritual and moral needs to constituting a problem

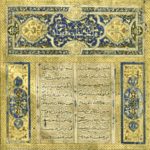

In the light of this, we need to discover the borderlines separating the proper sphere of the religion, and that of the parallel worldly sphere. This may be effected through applying various models of what is specific to religion or to science, to religion or to the state, and to the sacred and to the mundane. We need to establish the building blocks for understanding religion, and a compass to guide us in how we are to understand the verses of the Holy Qur’ān if we wish to construct a humane and faithful vision, one where we may view religion from a different perspective, one where religion becomes a cure not a disease, where faith liberates and not enslaves, where religiosity is a spiritual, moral, aesthetic state, one in which the sweetest image of God, man and the world is manifest.

A new approach will seek to re-read religious texts in the context of today’s practical reality, and discover the prerequisites for the spiritual, moral and aesthetic life of the religious believer in a world where the pace of transformation is accelerating. The common language of this re-reading is the ‘theology of mercy’, one that alleviates the ‘theology of the sword’ which tightened its grip in our past and whose effects are still active in our lives today. Since heroism and valour were the highest, most deeply rooted values in the life of the individual and the tribe on the Arabian peninsula, the logic of war prevailed in an era of conquests following the honourable prophetic Mission. As a result religious, social and cultural life were saturated with these values, and religious thought in Islam fell captive to them.

Thus the ‘theology of the sword’ prevailed over the ‘theology of mercy’, despite the dominating presence of divine mercy in the Holy Qur’ān, and the obligation to adopt this as the frame of reference for its interpretation. We can clearly see that the meaning of the Qur’ān is to seek mercy, yet most commentators neglected this, so that throughout the history of Islam the language of violence prevailed over the language of mercy. Many interpreters of the Qur’ān and many jurists frittered away the massive evidence of its stock of mercy, and the operative significance of the Verse of the Sword [2] in the Qur’ān became predominant.

Suggested Reading

A work such as Faith and Metaphysical Alienation seeks to awaken the religious conscience and alert it to the intensity of the presence of mercy in the Qur’an, and the strength of its significance, and how man has become existentially alienated from Allah in the theology of the scholastics. That theology excelled in carving out an image of God that simulates the relationship of master to slave that was an established fact in yesterday’s societies. In this antique scholasticism Allah was an authoritarian, much like the tyrannical kings, and His relationship with man was patterned like that of an owner towards his slaves, one who ‘owns’ people as the master ‘owns’ his slaves, ‘owns’ their destinies, and ‘owns’ everything in their lives.

The doctrine of Jabariyya[3] was born in the horizons of this antique vision and became the basis for legitimizing various forms of authoritarianism the length of the history of Islam. It also formed the background, via exposition and analysis, for what a cognitive mysticism could yield to fulfil the needs for religious meaning today, like some precious mine of spiritual, moral and aesthetic meanings. But to uncover what abounds in all the layers of this mine requires the presence of a brilliant detective who can dive into those layers and eek out the jewels buried in the rubble of a coal mine. Such jewels are written in an oftentimes opaque language, not without its excess of tediously obscure terminology, phrases and expositions in works that are at times tinged with exhortations to the reader to wander off and devote himself to applying the recommendations of the Shaykh of the ṭarīqa, which trains Mankind in a mysticism of enslavement.

[1] This essay is taken from the author’s work: الدين والاغتراب الميتافيزيقي (‘Faith and Metaphysical Alienation’) published by Dar Al-Rafidain, Beirut and the Centre for the Study of the Philosophy of Religion, Baghdad.

[2] The ‘Verse of the Sword’ is Qur’ān IX (al-Tawba), 5: So when the sacred months have passed away, then slay the idolaters wherever you find them, and take them captives and besiege them and lie in wait for them in every ambush, then if they repent and keep up prayer and pay the poor-rate, leave their way free to them; surely Allah is Forgiving, Merciful. On this, see Almuslih article The Verse of the Sword and the jurisprudence of violence. (Ed.)

[3] ‘Compulsionism’, the doctrine whereby mankind is devoid of free will over his actions, in that such would impugn the omnipotence and omniscience of God. See Glossary: ‘Jabariyya’.