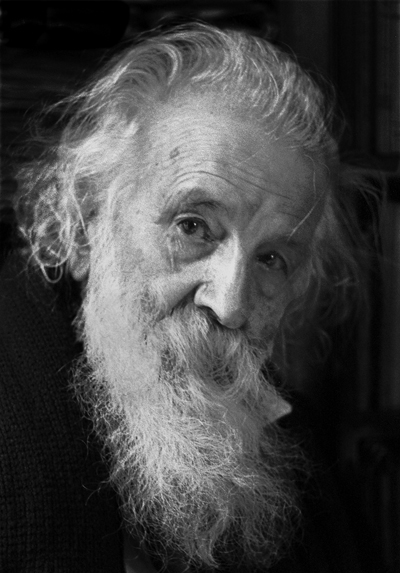

Nearly a century ago when Taha Hussein published his audacious book On Pre-Islamic Poetry in 1926, Arab thought stood at a crossroads: either it would adopt the scientific methodological approach in questioning its beliefs and heritage, or it would continue to ruminate on its deep-rooted illusions and ignorance. The second option was the one that prevailed.

IN THE FACE of a project for scientific enlightenment, a wasted, unrealized possibility persisted. If one of the axioms of scientific research, and a necessary condition for it to function, is the separation of faith from science, then the obviousness of this axiom passed unappreciated. Instead of dogma being subject to questioning, it remained pre-eminent and reinforced. In light of this, one can only stress the necessity of questioning belief, critiquing it and surpassing it, however high its societal ramparts are built. [1]

For dogma cannot be left to become a criterion for scientific endeavour. When we make belief a criterion for science instead of science a criterion for judging belief, we empty the scientific endeavour of its scientific nature and turns into something closer to a defensive theology or, at best, doctrinal tinkering or fabrication.

Truth between social obligation and scientific accountability

In the light of this complex social cognitive problem, we should distinguish how we understand the actual state and results of ‘Arab scientific research’ in establishing truth, given that there is a firmly-established and unanimously agreed upon ‘societal’ truth that imposes its sovereignty over the means, mechanisms and delimitations of knowledge production. This societal truth is a truth that has been socially assimilated and institutionally reproduced for a purpose serving the interests of dominant groups in the society, which we can represent variously as ideological realities imposed by the prevailing political systems, or religious beliefs entrenched in a society, or perceptions on race or gender biases, or other views subject to consensus and social coercion.

On the other hand, scientific truth is systematic knowledge, and it is founded upon systematic doubt, whether from the principle of verification (according to the empirical positivist approach) or falsification (according to the principle of Karl Popper).[2]

The Arabic term ‘ilm (‘science’) did not indicate ‘knowledge’ of the laws of nature, but was instead framed by a religious determinant

The essence of scientific knowledge lies in its ability to provide evidence (whether to prove or refute). It is a critical type of knowledge in its self-awareness, and its critical processes guarantee its openness, diversity and its development, so that one may talk about the history of science as the history of scientific errors, as Gaston Bachelard put it. Whereas, ‘societal truth’ is closer to the concept of an ideology, a fake knowledge that serves a specific group of society and reflects its interests.

Even so, to assume false awareness in societal truth is not to deny its importance in engendering a discourse of truth or to deny its social effectiveness. Truth, as Michel Foucault alerts us to, is itself a discourse; that is, it is a set of systemized rules that are themselves subject to regulating and controlling laws at a certain time in history.

Religion as a criterion for the discourse of truth.

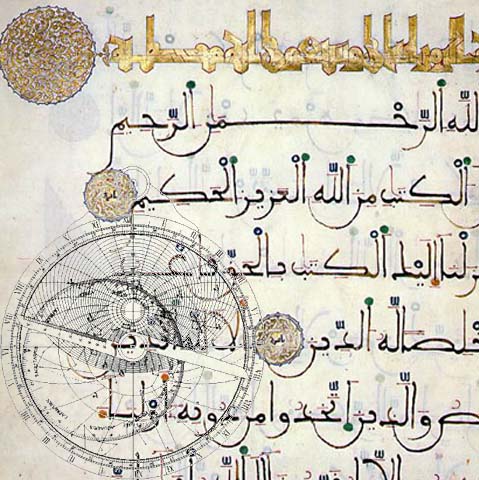

If Islamic civilization is based on the pivotal axis of the religious Text, then truth within this historical context cannot acquire legitimacy in itself or by its ‘proof’ except to the extent of its closeness or distance from that truth. For the religious Text, as a socially ingrained fact of belief is not merely a truth, but a criterion for truth, or ‘the truth of the truth’. It is its own necessary condition and has its own inherent assumption. And if we look back at Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī in his Revival of the Religious Sciences, we find that he bases his discourse on an obvious assumption in which he sees that: “the prestige of science stems from the prestige of that which is known”.

And because knowledge of God is more honorable, the religious sciences are all the more important. It is through them that the legitimacy of science is to be measured. Every science is thus a means to a religious end, and anything that departs from that is reprehensible. Accordingly, he classified sciences as either ‘praiseworthy’, or ‘reprehensible’, or ‘allowed’.[3] These are classifications which make science as something to be measured by fiqh (‘jurisprudence’). Knowledge is thus defined conceptually and expressed through jurisprudence, something which makes the religious purpose frame and govern the cognitive purpose. There can therefore be no independence for scientific knowledge from religious knowledge:

“Every science that does not lead to the knowledge of the Creator – may His Majesty be glorified and exalted – is useless and baseless, it is of little benefit and return”.[4]

In the context of this cognitive overlap between belief and science, we note also the lexical overlap between the two terms ‘science’ and ‘knowledge’ as it pertains to religion. The Arabic term ‘ilm (‘science’) in the way it was circulated in the ancient Arab context, did not indicate ‘knowledge’ of the laws of nature, but was instead framed by a religious determinant, and its dependent religious function. ‘Science’ here in its religious sense is

“hadith and related tafsīr (exegesis) and fiqh, along with its auxiliary sciences of linguistics, the history of the Prophet’s military campaigns (al-maghāzī) and the history of olden times”.[5]

The scientific scholar is thus the hadith-scholar, the faqīh (‘jurist’) and the mufassir (‘exegete’).

Within this diagnosis, the discourse of truth becomes absorbed into the religious discourse and in fact confined to it. In the face of this, knowledge cannot be a critical questioning of belief, but instead an exercise in ‘interpretation’ (the ‘science of tafsīr’) or apologetics (‘ilm al-kalām) or in confirmation and extolling (the ‘science’ of rhetoric and iʽjāz – ‘inimitability’ of the Qur’ān’s language).

Suggested Reading

Whereas the sciences and their associated curricula took shape within the trajectory of Western development, beginning with the era of the Renaissance and religious reform, passing through the skeptical Cartesian moment and Spinozan intellectual questioning, followed by the formation of the philological science – based on historical investigation rather than doctrinal, faith-based assumptions. They did not end at the point merely of employing contemporary human sciences for analyzing and interpreting the ‘sacred’.

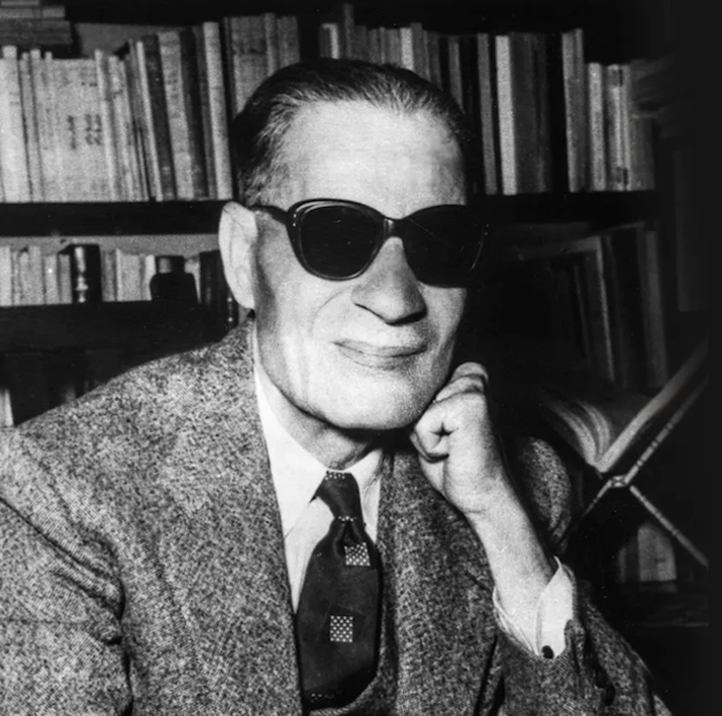

While this knowledge began to form and accumulate in the West, Arab-Islamic thought remained mired in its dogmatic lethargy, making religious knowledge the measure of truth. Perhaps this is what paved the way for, and aided contemporary Islamic political movements in to manipulate and enlist religious discourse to serve their political aims. Absence of any critical awareness concerning the Islamic heritage has led to an ideological political discourse expanding within it. As Mohamed Arkoun confirmed,

the Islamic heritage has not yet been subjected to the process of historical criticism, and it can thus be easily employed for violent purposes. Conversely, it is difficult for secularized European societies to employ the Christian religion to incite and justify violence. So long as Islamic thought is not subjected to scientific criticism, there can be no solution or salvation. [6]

The problem is firstly an internal one, and the disease is chronic, internal – contrary to what the Arab ideologues and Islamic fundamentalists both imagine.

If we borrow Kant’s phrase, the advent of the Arab nahḍa[7] awakened Arab/Islamic thought from its dogmatic slumber, and we began to witness several questions developing, as a liberating discourse began to form in multiple arenas. Three foundational books may perhaps best represent this: The Liberation of Women by Qāsim Amīn in 1889; Islam and the Principles of Government by ‘Alī ‘Abd al-Rāziq in 1925; and On Pre-Islamic Poetry by Taha Hussein in 1926.

The difference between these theses traces a profound shift in Arab thought and reality following the rise of the liberal emancipation movement, for the book On Pre-Islamic Poetry was not just a solitary voice, but was one among a group of voices and one that lay within a general liberal-enlightenment current. It is from this whole context that the battle that arose over the book may be seen as an expression of the movement of Arab thought, and an illustrative example of the changes that occurred in Arab society cognitively, politically and institutionally.

[1] The book was audacious because Taha Hussein revisited the question on the genuineness of pre-Islamic poetry, and hence the canonical tradition concerning the Arabic idiom of the Qur’ān. For this work see the Almuslih Library here (Ed.)

[2] The ‘falsifiability’ criterion is one which declares as non-scientific any proposed explanation that will not present ways of checking it, so as to confirm it or reject it as incorrect. Any hypothesis that is presented should state the test conditions that could render it false. (Miracles, or a statement from scriptural authority, are thus not falsifiable since there needs to be at least a theoretical possibility that they can come into conflict with observation. For whatever truths they might hold, they are not part of science. For more on this principle of falsification, see the Model Curriculum project of Almuslih, in A2: The Methodology of Science (see section A2.3.2 – Falsifiability, predictive power and repeatability (Ed.)

[3] Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, The Revival of Religious Sciences, Part 1, p.34.

[4] Al-Ghazālī, Maʽārij al-Quds, p.163.

[5] Al-Jābrī, تكوين العقل العربي (‘The Formation of the Arab Mind’), p.64).

[6] Mohamed Arkoun, نزعة الأنسنة في الفكر العربي الإسلامي (‘Humanism in Arab-Islamic Thought’) p.34.

[7] See Glossary.