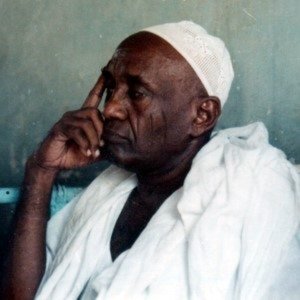

This year marks the thirty-eighth anniversary of the martyrdom of Professor Mahmoud Muhammad Taha, whom the Muslim Brotherhood, clerics and jurists together conspired to have executed on the charge of apostasy. In this his accusers identified with the Numeiri regime which tried him on charges of inciting hatred against the state. The conspiracy included the axis countries which harnessed their financial and media capabilities via their religious institutions – Al-Azhar in Egypt, the Muslim World League in Saudi Arabia – to rid themselves of him.

IN MY PERSONAL ESTIMATION, had Professor Mahmoud not been radical and true to his thoughts and writings, to his will for change, and to his principled determination to raise up human awareness out of the depths of ignorance and reaction, he would have been just one more of the celebrated Islamist extremists granted space in the media. As it was, his courage for the truth and principled commitment left him no helpers among the weak-minded crowd.

Professor Mahmoud took the side of the people, supporting them throughout his life, and he refused to align himself with any government or an opposition that did not serve the interest of the common folk. This was at a time when those pursuing their own interests and purposes against the people were legion, misleading them in the name of religion and exploiting them in order to maintain their own interests and perpetuating the revolving wheel of state failure. He stood at the forefront: when his disciples were imprisoned he was first among them, and was the first among them to stand trial. And when the great day of sacrifice came he personally shouldered the responsibility and did so with complete serenity, with his bright smile visible even on the gallows.

This was in contradistinction to how leaders of other parties behave, who send their followers into the fray and then come power over their corpses. The power of his mind was not such as to be restrained by politics:

“I despair for the Sudanese people, because they are a folk without leaders, or giants led by dwarves.”

And when religious affairs set out to distort his ideas, he maintained that “the Sudanese people are an authentic people, but they are ill-informed”. He was a pioneer in criticizing and exposing the pretenders to religious piety due to the steadfastness of his positions taken, arguing that:

“the day will come when a plank will be placed over the door at Al-Azhar inscribed with the words “Here was ignorance taught.”

In the cause of his enlightenment revolution, he wrote, lectured, organised free platforms and founded an intellectual resurgence by presenting Islam in a scholarly form that addressed minds, at a time when sectarianism and its offshoots became entrenched in the marketplace acting against their interests. That revolution was not one that could be monopolized by the élites, for its roots were in the streets, in the cities, villages and in the deep countryside, and addressed the minds and hearts of simple folk. He warned against the Islamists’ conspiracy:

“… the treachery of the Muslim Brotherhood, their lies, their coarseness, and their lack of religion will soon become clear to our people, and on that day their complete isolation will take place, isolating the Muslim Brotherhood from the religious call that they rant about, and Islam will be purified of the distortions and impurities they apply to it.”

And the revolutionary link between the October and December uprisings, are both of them creations of the people without any help from partisan leaders. These uprisings called for justice and the cleaning up of politics, and Professor Mahmoud placed his bets on the emergence of this generation that yearned for freedom and emancipation from the yoke of an inherited ignorance:

“the failures of the Sudanese people comes from their leaders, not from themselves, and the Sudanese people demonstrated this because they were the victors in the October Revolution without their leaders; had there been any leaders the October Revolution would not have taken place.”

Speaking of justice he argued that

“I am sure of one thing, that at time will come when this nation will hold these people accountable.. Do not imagine that the October Revolution’s cleaning up was in vain.. It was not achieved, but it was nevertheless the wish of the people.. The time will come when the cleansing will be implemented.. Because the people at that time will be stronger than they are now.”

A conspicuous feature of his intellectual radicalism concerned Sudan’s identity, its Africanness, and the plurality of its peoples. He did not call for a religious government because it would then be based on a faith, which would divides rather than unite. Instead he talked of a human constitution based on the instinctive principles of faith, a constitution that transcended religious beliefs and in which all Sudanese could secure their aspirations to a decent life. But for this to happen they had to make their contribution by openly expressing these desires and aspirations. He thus called for the establishment of a federal socialist democratic government, and opposed the precedent set of amending a fundamental article of the constitution, according to which the elected members of the Communist Party were to be dismissed from Parliament. He also opposed the attempts by the Muslim Brotherhood and by political parties to draft a constitution shrouded by the sanctity of religion, something which he called a ‘fake Islamic constitution’.

Evidencing this was the fact that Professor Mahmoud’s deep-rooted conception of national unity landed him in the prisons of the English colonizer when he opposed the decisions of the Consultative Council of Northern Sudan that sought at the time to separate off the south in June 1946 and again under the laws of September 1983, which he described as distorting Islam and threatening the unity of the country.

As for the issue of women, this was one of Professor Mahmoud’s most conspicuous radical positions, since he proposed the development of a legislation that would support the dignity of women, and accompany the gains and rights they had achieved. This was on the grounds that it was based on the Meccan Qur’ān – that is the very origins of Islam as opposed to the writ of Islamic law, with its distinct authoritarian and patriarchal nature that relies on texts that make men guardians over all women, irrespective of how mature and advanced they are.

Suggested Reading

The professor also raised the issue of ḥijāb as not being an essential feature in Islam, and moreover that the Islamic starting-point is to be unveiled, albeit going out in modest dress. He also argued that polygamy is not an essential feature in Islam, and that divorce and the marriage bond are just as much a woman’s right as they are of men. All these lofty values, which he had been advocating since the 1960s, have now become the cornerstone that the builders rejected, and now come looking for without any guidebook. All Islamic countries rely on the Sharīʻa’s personal status laws, and the difference between these reactionary laws and the actual advanced reality of womankind can be easily seen.

In the field of Islamic renewal and the modern understanding of the faith, Professor Mahmoud worked on resolving the glaring contradictions between the Qur’ānic texts and the commentaries of the jurisprudents, by freeing up the minds of individuals. He presented solutions suitable to their need for a decent life, by moving on from the subsidiary texts in the Medinan Qur’ān – which served the needs of seventh century societ – to the original texts of the Meccan Qur’ān that holds solutions to the problems of contemporary humanity. This is what he called The Second Message of Islam in terms of freedom of belief, freedom of opinion and economic and social equality, “for Islam in its First Message is unsuitable for 20th century mankind.” He felt convinced that Islamic law as a system of government was inapplicable, due to its inability to solve the problems of humanity and give rise to free individuals. His speech before the court encapsulated his radical self-identification as one of the people:

“The judges enforcing these laws lack the necessary technical qualifications. They have also morally failed to resist placing themselves under the control of the executive authorities which exploited them in violating the rights of citizens, humiliating the people, distorting Islam, insulting intellect and intellectuals, and humiliating political opponents. For all these reasons, I am not willing to co-operate with any court that has betrayed the independence of the judiciary and allowed itself to be used as a tool for humiliating the people, insulting free thought, and persecuting political opponents”

Mahmoud Muhammad Taha: final testimony before the court that condemned him to death