Ask those shaykhs who issue fatwās in the name of religion, those clowns who have appointed themselves leaders of Islam, or those simple-minded people who wore the clothes of piety and claimed that they were guiding people to the Straight Path – ask them this: have they read the Mathnawī by Jalāl al-Dīn al-Rūmī, have their ears been caressed by the poems of Rābiʽa al-ʽAdawiyya on divine love, have they understood anything of the wisdom of the great shaykh, Muḥyī al-Dīn ibn ‘Arabī, and can they explain a single paragraph from the work The Wisdom of Illumination by al-Suhrawardī, or are they aware that all Islamic theology (kalām) is founded upon Ibn Sīnā’s philosophy, which in turn was derived from the Greeks?

THE GROWTH OF religious extremism and its transformation in many cases into acts of terrorism, the suffocation it has caused to society and its natural development, is not merely a product of the weak state of our modernity (a major phenomenon and a peril in itself), but carries within it an added disaster: the severe level of cut-off that has taken place between Muslims and their religious and spiritual heritage. Modern preachers have replaced that rich heritage with easy-to-digest jurisprudential acronyms that suit their modest level if intellect. As they peruse these acronyms, it appears to them that issuing a religious fatwā is a simple matter, and they have thus set themselves up as jurists without knowledge and as scholars without knowledge. You can see among their number those who have failed in their studies and become infamous for their bad morals. Suddenly penitent, they have grown their beards and turned jurist, doling out fatwās on what is permissible and what is forbidden, and speaking in the name of God and the religious law.

This is not some accidental or anomalous phenomenon, given that most aspects of the Islamic spiritual heritage have been neglected, with only the jurisprudence for the masses remaining, something which has turned into its own religion. Discourse in the name of, and about, Islam has become inflated particularly since the seventies, which was a period that saw an almost total absence of any attempt to develop a new religious thought in Islam. What is worse, the estrangement of Muslims from their religious heritage is not merely one of major figures of the past, but includes personalities from the modern period too, people such as Muḥammad ‘Abduh (1849-1905) and Muḥammad Iqbal (1873-1938).

They have thus set themselves up as jurists without knowledge and as scholars without knowledge

Nothing says more about the astonishing regression demonstrated by the state of contemporary Islam than the number of fatwās that have attained the outer reaches of weirdness, such as the fatwā of ‘Doctor’ Ezzat Safi that solved the problem of a man and a women finding themselves alone together in the workplace by means of a legal legerdemain, whereby a woman should breastfeed her colleague in order that he become thereby ‘forbidden’ to her.[1]

Similarly, the Egyptian mufti opined on the permissibility of deriving blessings from drinking the Prophet’s urine [2] and his fatwā banning images and statues in a country that derives its living from tourism to its Pharaonic antiquities. The official muftī went on to meet with the banned Taliban group, which had previously instigated the destruction of Buddhist statues that had coexisted with Islam ever since the faith reached Sindh and India. Likewise, Shaykh Al-Qaraḍāwī issued a fatwā detailing how Islam prohibits statues and all anthropomorphic images:

“Some say that this was in the era of paganism and idolatry, but that now there are no worshipers of idols any more. But this is not correct. There are still people who today worship idols, who worship the cow, or the goat. So why do we deny reality? There are people in Europe who do this no less than those pagans: you can find traders hanging horseshoes on their shops, for example, and people still believe in superstitions. There is a kind of weakness in the human mind, and even intellectuals fall prey to some of the most evil things that even the mind of an illiterate doesn’t stoop to. Islam cautioned against and prohibited everything that leads to paganism or reeks of paganism, and it is for this reason that it prohibited statues, and the ancient Egyptian statues are equally subsumed under this”.

A century before the fatwās of Ali Gomaa and Yusuf al-Qaraḍāwī, an enlightened religious scholar in Egypt occupied the position of Iftā’, the bureau issuing fatwās. He was asked the same question and he answered with the following:

“The artist has created the image, and the benefit of this Is undisputable. The idea of worshipping and glorifying statues or images is something that has by now been erased from the minds.”

He then went on to respond to the objectors who invoked the hadith, “Verily the most grievously tormented people on the Day of Resurrection would be the painters of pictures”,[3] by saying:

“This hadith goes back to the days of paganism when pictures at that time were used for two purposes: firstly for amusement and secondly for deriving blessing from the righteous figures represented by them. The first type the faith deplores, and the second type Islam came expressly to abolish. In both cases the image-maker is ignoring God or is actively paving the way for associating others polytheistically with Him. If these two symptoms are removed and a positive purpose is intended, then the depiction of people is no different from depicting plants and trees.”

He then went on to lament:

“Muslims only make requests (meaning: they only seek fatwās) for things that they may derive joy from, just in order to deprive themselves of it … Have you heard of any of use keeping anything else than pictures and drawings? The faculty of memory is not something that is we inherit; what we inherit is the faculty of bearing grudges and resentments and hatreds. These are passed down from parent to children, corrupting worship, ruining the country. Those who promote this shall all meet together on the edge of the abyss of Hell on the Day of Resurrection”.[4]

Suggested Reading

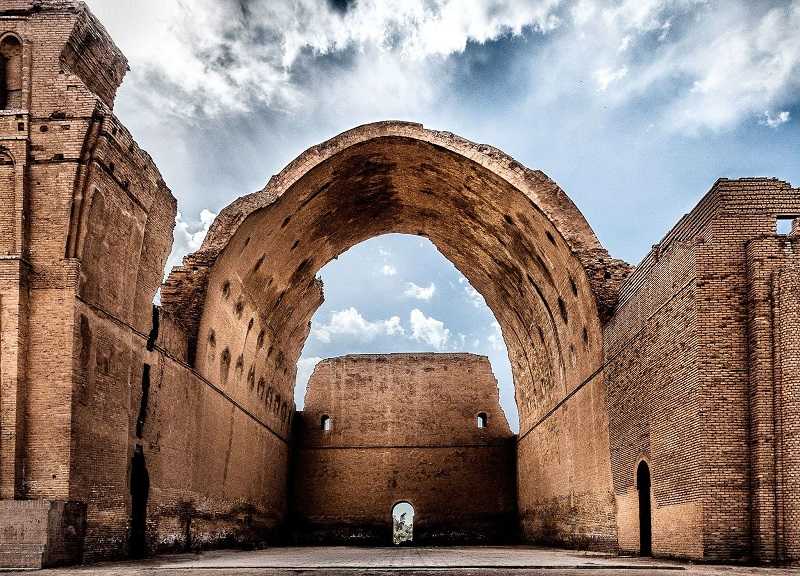

Ibn Khaldūn before him recorded the foolishness of those contemplating destroying statues and antiquities. He mentioned that Harūn al-Rashīd was determined to demolish the Arch of Ctesiphon (the Tāq Kasrā or Īwān Khosrau)[5]:

He sent to Yaḥyā bin Khālid Al-Barmakī to ask his advice on that, and he replied: “O Commander of the Faithful, do not do this. Leave it as evidence for the power of the dominion of your fathers, who despoiled the kingdom of those who built that temple”. He then went on to condemn his advice saying: “The haughtiness of the Persians has overcome him” and set about to demolish it. He gathered together workmen with pickaxes, ringed it with fires, poured in vinegar but after all of that effort he was left exhausted. Fearing humiliation, he sent again to Yaḥyā asking for his advice about giving up. This time the latter replied: “Do not do that, keep going, so that no one will say that the Commander of the Faithful and the King of the Arabs was impotent to destroy a Persian monument.” Al-Rashīd nevertheless conceded and abandoned the effort to destroy it.[6]

But the jurists of our era do not read Ibn Khaldūn. And as for Muḥammad ‘Abduh, the fundamentalists said that he was no reformer, but merely a shaykh who was fascinated by the West. It is as if Muḥammad ‘Abduh had foreseen how the Islamist movement would turn backward, from the words he uttered on his deathbed:

I care not whether they say Muḥammad survived or had many mourners at his death;

What I fear most is that the faith I sought to reform should be finished off by the turbans.

[1] The man thus becomes a maḥram – a ‘forbidden’ relation to her in the sense of thus being transformed into the role of a suckling infant. The issuer of the fatwā in question was Head of the Department of Hadith at Al-Azhar University, who was subsequently fired because of the embarrassment his fatwā caused. In his defence he maintained that “My statements on the issue of breastfeeding an adult were based on the imams Ibn Hazm, Ibn Taymiyyah, Ibn al-Qayyim, al-Shawkani and Amin Khattab, and on conclusions I drew from the statements of Ibn Hajar.” The fatwā remains a subject of controversy, with critics pointing to the evidence of Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 1452 that has ‘Ā’isha stating that the Qur’ān’s original stipulation of 10 breastfeedings to turn a man into a maḥram, was abrogated and reduced to five “and the Messenger of Allah passed away when this was among the things that were recited of the Qur’ān” before the verse was subsequently lost after a sheep ate it when it had been stored under her bed (Sunan Ibn Μājah, 1944). For Ibn al-Qayyim the ḥadīth is not abrogated since “It is neither specific (to that case), nor is it broadly applicable. It is simply a license addressing the need of someone who has to enter upon a woman, and from whom seclusion is burdensome” (Ibn al-Qayyim, زاد المعاد 5/527). (Ed.)

[2] A number of hadiths supporting this are available on the internet, for example the Islamic education website. (Ed.)

[3] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2109a . The impulse towards destroying statues and monuments from the pre-Islamic era remains strong. See, for instance, this entry on the online fatwā site Islam Q&A. (Ed.)

[4] Muḥammad ‘Abduh, الأعمال الكاملة, Vol.2, pp. 204-208.

[5] Tāq Kasrā is the remains of a Sasanian-era Persian monument, dated to c. the 3rd to 6th-century, which was the facade of the main palace in Ctesiphon. Its massive archway is the only visible remaining structure of the ancient capital city and is considered a landmark in the history of architecture, as the second largest single-span vault of unreinforced brickwork in the world. (Ed.)

[6] Ibn Khaldūn, Al-Muqaddima, Ch. 4, section: ‘Very large monuments are not built by one dynasty alone’. Ibn Khaldūn goes on to describe how “the same happened to Al-Ma’mūn in his attempt to pull down the pyramids of Egypt. He assembled workers to tear them down, but he did not have much success. The workers began by boring a hole into the pyramids, and they came to an interior chamber between the outer wall and the walls further inside. That was as far as they got in their attempt.” (tr. F. Rosenthal, The Muqaddimah, An Introduction to History, Routledge, London, 1978, pp. 266-7). (Ed.)

Main image: The ‘Arch of Ctesiphon’ at al-Mada’in south of Baghdad.