One simple question: this Mushaf [1] that we read from (to whatever extent we can), or intone loosely from the Fātiha to the Muʽawwidhatayn [2], or swear by on some occasions – is it the same Qur’ān in its entirety as the one that the Seal of the Prophets left us, in word order, collation, script and grammatical inflection?

BY SAID NACHID

IS THE MUSHAF of the Caliph ‘Uthmān itself indisputably the Qur’ān of Muhammad? Answer: a resounding ‘no’ in bold letters. How so?

1) Let us begin at the appropriate place – the ordering of the Qur’ān. Was it like this in the time of the Prophet Muhammad?

It is common knowledge that the decision to collect and order the Qur’ān and place it in the form of a single codex, was an arduous and complicated project begun by the Muslims following the death of the Prophet during the caliphate of Abū Bakr al-Siddīq, and completed in the time of the caliphate of ‘Uthmān ibn ʽAffān. The ‘Uthmānic text was subsequently subject to many vicissitudes of writing down, grammar and penmanship over the course of the centuries, so that today we cannot be certain as to the original form of the copy presided over by ‘Uthmān. Apart from that, the Prophet left behind a Qur’ān whose verses were incomplete, scattered and dispersed, mostly oral in origin and always characterised by an oral form. He died and did not leave it organised in any single volume or in a definite text, nor did he give any instructions to do so.

Al-Qurtubī writes:

During the time of the Prophet the Qur’ān was dispersed amongst the breasts of men, and people wrote it down on leaves, palm branches, likhāf (soft white stone), turar (stone with edges like that of a knife), pottery and what have you. When the rate of casualties amongst the Qur’ān reciters became serious at the Battle of al-Yamāma during the time of [Abū Bakr] al-Siddīq, where it was said that something like seven hundred of them were killed that day, ‘Umar ibn al-Khattāb advised Abū Bakr al-Siddīq to collect the Qur’ān for fear that the reciters like Abū and Ibn Masʽūd and Zayd might perish. They delegated this to Zayd ibn Thābit and he collected it together after much toil but without any ordering of the sūras.[3]

Today we cannot be certain as to the original form of the copy presided over by ‘Uthmān

However the turning of the Qur’ān into a Mushaf did not take place until the time of the third caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ʽAffān, and in this regard the tale narrated by many runs along the following lines:

Ibn Shihāb said: ‘Anas ibn Mālik al-Ansārī told me that the Syrians and the Iraqis gathered together for the raid on Azerbaijan and Armenia. On hearing about their divergences concerning the Qur’ān Hudhayfa ibn al-Yamān rode to ‘Uthmān and said: “People are differing on the matter of the Qur’ān so that I fear that they may suffer what happened to the Jews and the Christians concerning divergences.” Whereupon ‘Uthmān became greatly angered and sent for Hafsa and took out the copy which Abū Bakr ordered Zayd to collect[4] and he made several copies of this and distributed them widely.’[5]

Indeed it is widely known that the ordering of some of the verses was carried out on the basis of consensus, or arbitrarily in some cases. Examples of this were furnished by Abū Bakr ibn Abī Dā’ūd al-Sijistānī in his account:

‘Umar ibn al-Khattāb wished to collect the Qur’ān and addresses of people saying: “Let anyone who has received any piece of the Qur’ān from the Prophet of God bring it here.” They had written these pieces in the Mushaf and on the stones and grass and none of them were accepted unless there were two witnesses to attest to it. While he was collecting these he was slain and ‘Umar ibn al-Khattāb said: “let anyone who has a piece of God’s book bring it here.” None of this material was accepted without the attestation of two witnesses. Then Hazīma ibn Thābit stated: “I have seen that you have left out two verses which you did not write down.” He asked: “What are they?” and was told: “I received from the Prophet of God: There hath come unto you a messenger, (one) of yourselves, unto whom aught that ye are overburdened is grievous, full of concern for you, for the believers full of pity, merciful”[6] and so on to the end of the sūra. To which ‘Uthmān responded: “I bear witness that this is from God; where do you think that we should insert it?” He replied: “put it at the end of this is the last verse revealed of the Qur’ān.” And he concluded the Sūrat Barā’a [al-Tawba] with it.’

This account, on which most writers on the heritage concur, raises a very complicated question. In that even if we were to assume in mitigation that the condition of two witnesses to clarify the verse before recording it was enough to guarantee against the insertion of non-Qur’ānic verses into the Qur’ān, this condition does not satisfy two basic purposes:

Firstly, it doesn’t guarantee for us that there are no gaps in the memory of the one giving the dictation, or the grammatical judgements made by the one responsible for the writing up, especially since the Arabic language had not been subjected to standardisation, or at least not yet.

Secondly, it does not guarantee for us that no verses were overlooked which might have been part of Muhammad’s Qur’ān but which did not have two witnesses to vouch for them, or had only one. Perhaps the aforementioned verse which Hazīma ibn Thābit recalled, before it had been agreed upon to insert it at the end of the Sūrat Barā’a, would have been passed over had not ‘Uthmān volunteered to vouch for its being from God. Note that he bore witness that it was from God, and did not testify that he had heard it from the Prophet of God, which would be more usual in such a situation.

The volume of the Qur’ān which has reached us is much smaller than the volume of Muhammad’s Qur’ān

2) Regarding the quantity of the contents – does the Mushaf which we have in our hands contain all the verses of Muhammad’s Quran?

We are sure of one thing, and that is that the volume of the Qur’ān which has reached us is much smaller than the volume of Muhammad’s Qur’ān, that is, it is smaller than the collection of verses which were revealed to the Prophet. We have two basic textual evidences for this:

a) At the very least, we do not have in the body of the ‘Uthmānic Mushaf the abrogated verses or the forgotten verses. It is known that among the abrogating and abrogated verses there are verses whose phrasing, meaning and writing were duplicated, there were verses which the Prophet forgot about before recalling them again or dictating them, or before the recorders of the revelation wrote them down. Perhaps everyone forgot them after that and they were not revealed afresh, or at least they were not re-revealed in the same form. And this is confirmed by the following verse:

Such of our revelation as We abrogate or cause to be forgotten, but we bring (in place) one better or the like thereof. Knowest thou not that Allah is Able to do all things? (Sūrat al-Baqara, 106).

b) At the very least, what was omitted was the various form and expression in which some or most of the verses were revealed. As is known and related, the Qur’ān was revealed in seven ahruf[7], which indicates that many of the verses were revealed more often than not in different phrasings, expressions and words. However during the course of the collection of the Mushaf this linguistic variegation was dispensed with in favour of one single reading, that being the language of Quraysh.

The transformation of Muhammad’s Qur’ān into ‘Uthmān’s Qur’ān was a lengthy, onerous, thorny project replete with peril

This is at the basic level which the textual evidence can confirm. But the issue is apparently much greater than that, in that traditional studies of the Qur’ān conclude that it is likely that some of its verses or sūras have been lost. This issue did not embarrass Muslims who considered such a loss to be subject to the expressions that were replaced, or things that had been forgotten. This accords with the position taken by the Qur’ān itself: Such of our revelation as We abrogate or cause to be forgotten, and so on.

The transformation of Muhammad’s Qur’ān into ‘Uthmān’s Qur’ān was a lengthy, onerous, thorny project replete with peril. It is a project which the Arab thinker George Tarabishi termed the Pagination of the Qur’ān.[8] Without exaggeration, we find this totally inspiring since we said that the collection process continued on after the death of ‘Uthmān, in that the Mushaf of ‘Uthmān was itself subject to alterations that accompanied the development of the language and the transition of Arabic culture from an oral to a written phase. Between the first copy of the ‘Uthmānic Mushaf and the later copies, the nomenclature of the sūras passed through a number of processes, while the pointing of the text[9] saw several stages and the writing of some of the letters underwent many modifications.

Suggested Reading

The problem is that since the time of ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān Muhammad’s Qur’ān has been transformed into a ‘sacred’ Mushaf – whose sanctity was increased by the account of the Mushaf being bespattered with ‘Uthmān’s blood.[10] It became a closed text in the order of its verses and sūras, and no opportunity is allowed any longer to reorder its parts in a way that differs from the official Mushaf. Consequently Muslims have lost any interpretive possibilities presented by the disjointed and scattered nature of the verses of Muhammad’s Qur’ān. In the end this has impoverished any possibility of reinterpreting Qur’ānic discourse and has confined it within a narrow circle, a narrowness only increased by the fact that the pagination of the Qur’ān was carried out in the ancient world, so that it came to be branded as sacred both in form and content.

[1] Mushaf: the codex, the physically bound volume of the Qur’ān (Ed.)

[2] The Fātiha is the opening sūra of the Qur’ān; the Muʽawwidhatayn are the final two sūras, the sūrat al-Falaq and the sūrat al-Nās. They are so named since each contain the phrase aʽūdhu (‘I take refuge in…’) (Ed.)

[3] Al-Qurtubī, الجامع لأحكام القرآن ed. with annotations by Muhammad Ibrāhīm al-Hafnāwī, Dar al-Hadith, Cairo, 2nd ed. 1996, p.67.

[4] This is the copy possessed by Abū Bakr during his caliphate, then passed on to ‘Umar during his caliphate and subsequently left by ‘Umar with Hafsa.

[5] Abū Bakr ibn Abī Dā’ūd al-Sijistānī, كتاب المصاحف ed. Muhibb al-Dīn ‘Abd al-Sabhān Wāʽiz, Dar al-Bashair al-Islamiyya, Beirut, 2nd ed. 2002, Vol. I, p.202.

[6] Qur’ān IX, 128.

[7] The seven ahruf (‘letters’) refer to the seven different readings of the Qur’ānic text which Sunni Muslims hold to be valid. These variant readings include differences in grammatical declension, abbreviated or extended expressions, prior or later positioning of texts, differences in how to pronounce certain words and forms of words. (Ed.)

[8] George Tarabishi, إشكاليات العقل العربي Dar al-Saqi, Beirut, London, 4th ed. 2011, p.63.

[9] The Arabic script originally did not show dots differentiating a number of consonants. These were introduced later as a result of the confusion caused to non-native readers of the language. (Ed.)

[10] A copy of the Qur’ān held in Tashkent is said to contain blood spots from the occasion of ‘Uthmān’s assassination in 656 AD. However, its authenticity is disputed, due to spelling mistakes and the lateness of its Kufic style of script. (Ed.)

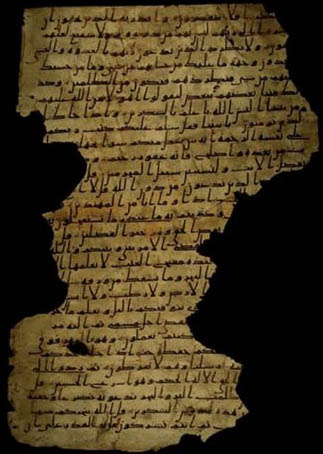

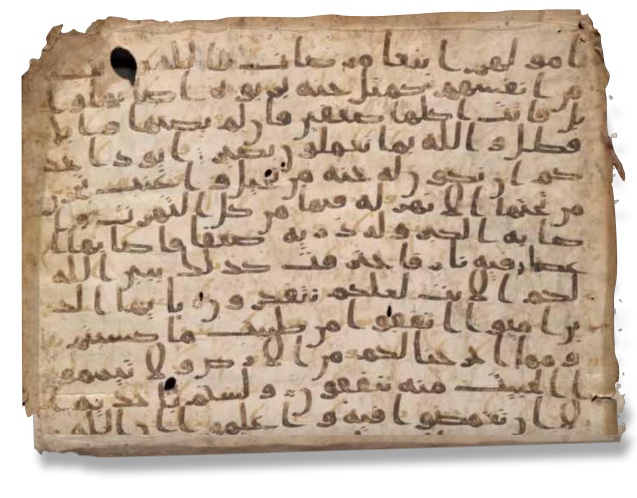

Main image: The San’a Palimpsest (c. 670 AD), the only known extant copy from a textual tradition other than the standard ‘Uthmanic tradition. The upper text conforms to the standard ‘Uthmanic Qur’an, whereas the undertext contains many variants to the standard text.