Definition of Salafism: Linguistically the term ‘salaf’ means ‘what has passed’. Technically speaking it is a Golden Age which represents the pure understanding and application of religious and intellectual authority, a time that predates the emergence of the differences, contradictions and denominations that overtook Islamic intellectual life as a result of wars and conflict.

IN THE SAME CONTEXT, and subsequent to the salaf – as represented by the Companions, the Tābiʽūn,[1] the great Imams of the major denominations, the Followers of the Followers – come the chronologically later ‘khalaf’, followed by generations of ‘those who came after’, the ‘moderns’ and the ‘contemporaries’.

According to Muhammad ʽAbduh, ‘Salafism’ denotes the understanding of the Islamic faith the way the nation’s ancestors understood it prior to the emergence of differences, and denotes a return to the original sources for the acquisition of knowledge. Despite the clarity of this definition, a multiplicity of Salafist factions took shape, each distinguished by their tactics and strategies. Some of them maintained the transparency of the texts, others employed the intellect in distinguishing between excessive and restrained levels of interpretation, others resorted to violence and still others focused on preaching.

Salafism – or Salafisms

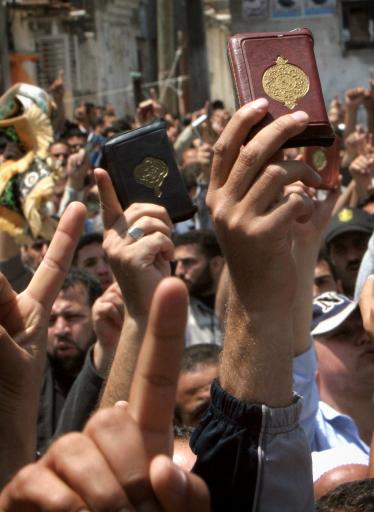

Salafism, therefore, is more properly a case of Salafisms in the plural: ‘Jihadi Salafism’ propounds revolution against ruling regimes, while ‘Daʽwā Salafism’, or ‘Scholarly Salafism’ espouses the idea of withdrawal, calling for the purification of one’s belief and the believer’s unquestioning acceptance of it. Salafism manages a network of Qur’ānic schools in Tunisian towns and villages alongside the official institutions, and it harnesses social networking sites to deliver their message to the masses. Salafism has instrumentalised the ordeal of Muslim prisoners, particularly those in Tunisia, who fought in the ranks of ‘Al Qaeda in Iraq’ and of prisoners languishing still in Iraqi (and today Syrian) gaols, for the purpose of building up their support and sources of funding.

A multiplicity of Salafist factions took shape, each distinguished by their tactics and strategies

Salafism has also benefited in Tunisia from mosque networks knitted together by building, maintenance, repair and outfitting corporations, and from mutually cooperative and harmonising communications networks that serve to strengthen the movement at the grass-roots level. However much their convictions and practices differ among themselves, Salafists in general share a number of characteristics:

- Textualism, or the literal reading of the Qur’ān

- The prioritisation of ritual practices at the expense of spiritual values, the promotion of ‘formalised’ behaviour in public spaces

- The employment of violence which can take either blatantly physical, or covertly symbolic, forms.

Symbolic violence, according to Bourdieu[2], is

a form of gentle, sweet, almost imperceptible violence, something invisible even to its victims; this form of violence is practised in symbolic ways and means

such as language, education, instruction, culture, methods of socialisation and forms of communication within the community. It inflicts damage on others without causing a disturbance, and indeed those upon whom this violence is practised might not even consider it to be violence and may themselves cooperate in its production and promotion, as if there were some existential inevitability to it, or as if it constituted an absolute, established truth to be automatically accepted. Bourdieu calls this type of this receptivity a ‘tacit, secret conviction’ that imposes its hegemony, authority, discrimination and inequality between the self and the other, between a man and a woman, between rich and poor – and it religiously and ethically legitimises it. He does not consider this to be the result of any historical or cultural fact, but rather as the result of some innate, natural, sacralised phenomenon that brooks no questioning or doubt, and indeed considers such things astonishing.

The result of some innate, natural, sacralised phenomenon that brooks no questioning or doubt

It is worth noting that it was the events of September 11, 2001 in the United States that drew the world’s attention to these marginal movements, with some circles considering that it was the Salafist theoretical framework underpinning these movements that was morally and subtantially responsible for this massacre. This is because it provided the sacralised authority in which the perpetrators of these events could immerse themselves. It is for this reason that this phenomenon became the object of much interest, in the light of which strategies were drawn up at the international and regional level, albeit the interest basically focused upon economic and political factors.

It is rare to come across studies in political psychology that make reference to psychological authorities when attempting to explain the phenomenon, or studies that employ the methodology, conceptions and theories of psychology for analysing the behaviour of actors in this political movement, or indeed any studies adopting a psychological terminology when seeking to interpret the important standpoints and decisions of these actors. It may be that this approach constitutes the missing link binding together the superstructure with its economic foundations, since it attempts to understand the unconscious factors driving a behaviour which is

not solely the result of an economic struggle, as Marx would have it, nor the product of a sexual conflict, as Freud would have it, but is in fact the outcome of existential dimensions of a personal character, social in origin and holistic in framework.

The current consensus affirms that the individual is par excellence an integrated biological, psychological and socially interacting unit.

In his study on interconnectedness and social cohesion within the army or the Church or the political party, Freud had previously wondered – starting from an analytical approach – about the function of political passions in intensifying social exchange. His research prompted questions concerning the place and status of psychological mechanisms in political life, and their origins and effectiveness. Reich followed up on these impressions, arguing that:

the psychological-analytical approach is not inconsistent with the material approach to political phenomena; on the contrary it supplements it. From another angle it broadens the field of research, and demonstrates that we are not merely to look into the political ideology of official institutions, but investigate all the various scattered sources and social structures, all the relationships of work and the forms of school and family upbringing, and all the patterns of religious piety. Within this perspective, the analytical process becomes more ambitious and, by means of political ideology, attempts to reveal emotional patterns in a particular society, at a specific moment in its history.

It seems, then, that the analytical approach to political phenomena does not put itself forward as an alternative to dealings of history and society; it presents itself as an alternative supplementary interpretation.

For instance, when the analyst Reich studied the phenomenon of fascism (and contrary to the prevalent opinion that held that fascism had been imposed on the broad masses by a minority with the use of force) he felt that it constituted a genuine response to the deep-seated wishes of these masses. Reich stressed the importance of the close relationship that bound together the instinctive drivers of authoritarianism with fascist ideology, and held that it was the authoritarian upbringing of the family that constituted the nucleus of the authoritarian state. This is because the ‘psychology of the masses’ is easily influenced by antidemocratic fascist propaganda and is always ready to accept the yoke of any authority that is capable, by means of pomp and public display, of fulfilling unconscious needs and drivers lurking in the depths of the human psyche.

In 1941 the renowned psychologist Eric Fromm[3] published a book that subsequently became famous: Escape from Freedom. Fromm examined the phenomenon he observed of the majority of his fellow German citizens thronging to the racist dictator Hitler, who never for a single day concealed his racist and dictatorial nature.

What, then, are the essential psychological mechanisms and drivers of the Salafist phenomenon?

The psychological mechanisms of religious extremism

The crushing of the individual as an individual

The totalitarian project is distinguished generally by the way it opens wide the door to oppression against all individuals without exception, irrespective of nationality, sect or class. It is hostile to everything that it sees in the realm of humane feelings, of art or language or anything that can put the lie to its totalitarian claims or upset the comforting fantasies on which these depend. The totalitarian project persecutes every tendency towards individualism and its natural association with all that is human, sensuous and cultural, with the desires and pleasures of liberty.

It can capture and freeze the individual in a state of perpetual infantilization

Why is this so? Because by disabling these trends it can capture and freeze the individual in a state of perpetual infantilization, in a pre-Oedipal stage of sexuality, and force him to indulge in oral, sadomasochistic phases of sexual arousal. These phases fit in with situations of fascination and identification, with relationships of obedience, subservience and masochistic submission intimately bound up with the ruler and the leader. This leader is exalted to the status of the ego, he plays the role of society’s father and fulfils a primordial desire that lurks deep in mankind from the cradle to the grave – a craving for the affection and protection of a strong and loving father.

The search for a father to society

Many scholars raised the problem of ‘fatherless societies’ that are experiencing a crisis of authority and identity due to the destruction of the traditional family and the dismantling of its timeworn social fabric, as well as from the collapse of traditional sources of societal power and the loss of legitimacy and credibility of major institutions such as the school, political parties and trades unions which served to qualify and train the youth.

Salafist movements provide a fortified stronghold for many of these groups of marginalised youth. These groups are in search of a social father who will protect them from the vicissitudes of a disintegrating society that is forcing them to search for protection from the implications and burdens of real life. It does this by means of a time-honoured, simplistic, idealised discourse, one that provides ready-made solutions to all of life’s contradictions. These groups are fully primed for total compliance to an ideology or a party line. The ruling ideology is assembled from all that is traditional, inherited and deep-rooted, and it therefore cannot brook any thinking that stands in competition with it or tolerate any opposing standpoints. With time, authoritarian institutions develop a conspicuous organisational principle: an authoritarian hierarchy, an obedience to the leader whereby orders issued from top to bottom are to be strictly implemented without hesitation or demur.

In this way a culture of blind political obedience to the leader develops, and consequently the movement or the organisation, with its hierarchical structure, imposes an authoritarian submissiveness.

The authoritarian personality

Unprecedented political changes and the fascist domination of power in Germany during the Second World War drove the pioneers of the Frankfurt School to undertake a study of the authoritarian mindset. The philosopher Herbert Marcuse[4] began to uncover the issues associated with the concepts of freedom and power and one of the first to be influenced by his concept of the authoritarian personality was Eric Fromm. He focused on the importance and role of collective repression that coerces society, and in particular the patriarchal family, and attempted to apply this to the ‘fascist personality’ whose make-up presents a sadistic personality. From that date Fromm’s analyses provided the basis for a wide-scale project that investigated the social and psychological foundations of the authoritarian personality that acts as a hindrance to the construction of a democratic system of values.

The founder of the Frankfurt School, Max Horkheimer[5], specialised in studying the theme of the family and power and the causes of aggressiveness that develops from childhood due to the suppression of his needs by the traditional family, which imposes upon the young obedience to one’s elders and transforms those who are weak into ‘deficient’ people. Horkheimer places the responsibility primarily upon societal pressures and repressions, things which generate an asymmetry and disharmony with society and a lack of adaptation to its hierarchical structure. Hence the child, or group or social unit to which he belongs, adopts the prevailing ‘pattern of thinking’ just as he adopts the same standpoints and expresses the same prejudices as a result of his limited knowledge and experience, and due to the weakness of democratic education.

According to the intellectual Theodor Adorno[6] one may define the characteristics inherent to this personality – which form its tendencies, trends or convictions associated with each other in a dialectical relationship, and which more often than not form a coherent ‘mental’ or ‘structural’ mode of thinking, activity and behaviour – as the following:

- Self-centredness and ethnocentrism

- Attachment to the past along with intolerance and hard-line attitudes towards any new foreign ideas and values;

- A propensity for conservative political, economic and social ideas that are hostile to democracy;

- Rejection of objective ideas and standpoints, and an interest in determinism or fatalism and the like;

- Commitment to traditional models and forms, along with a rejection of aesthetics, utopianism and critical thought, the refusal to recognise diversity and the right of the individual to choose his values independently of his religious or ethnic group;

- Compliance and identification with power;

- Excessive attention to issues of nationality, albeit in a hidden or covert form;

- A tendency towards zero tolerance of the Other and a lack of respect for different ethnicities, minorities and religions.

The obsession with cleanliness, purity and the purification mania

The extremist project fuels an obsession with identity in its superficial and primitive sense; that is, an identity that is closed in upon itself and made to contrast with the Other. Consequently we see how it affirms and demands religious exclusivity, through an exclusive sacralised language, an exclusive Book, an exclusive Nation – ‘the best community that hath been raised up for mankind’[7] that will fill the lands of Islam with justice after these lands had been filled with oppression. The obsession for unity and unification leads to enmity and rejection, and in some cases to the destruction of everyone and everything that threatens the illusion of harmony and unanimity, or gives the lie to these hallucinatory claims.

It affirms and demands religious exclusivity, through an exclusive sacralised language

Why is this so? Because it exposes the group to danger – the dangers of doubt, of upsetting accepted certainties, of division, of stirring up inevitable conflicts and contradictions. Here it will be useful for us to recall that in psychological analysis illusion is not a matter of confused perception but is rather the realisation of unconscious desires and effecting a more pleasant substitution of bitter reality. As Freud put it: “We call any thought an illusion when the attainment of some desire is the basic factor driving it.” Anyone who differs in terms of race, religion or nationality, any critical intellect or freethinker, any new sciences or any imported modes of behaviour are fantasised as being poisonous, polluting elements that threaten the fragility and purity of the Nation’s body – which in the collective subconscious becomes identified with the body of a pure mother. This goes to explain the extremists’ rejection of diversity, of the right to differ and the repudiation of the rights of religious, racial and sexual minorities.

Fuelling and nourishing micro fascism

In his definitive work The Mass Psychology of Fascism the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich defines ‘microfascism’ as ‘a collection of irrational emotional reactions in an average human being suppressed by an authoritarian civilisation that hinders the three sources of natural vitality: ‘love, creative employment and rational knowledge.’

Microfascism contributes to the production and nurturing of human chagrin, in particular sexual dissatisfaction (10,000 consumers of brothels per day in Tunis, according to statistics provided by the National Bureau of Family and Human Development), the manifestations of which we see in the reactions to emotional repression that takes shape in hostile outbursts or religious obsessiveness, of religious mania glorifying pain and submissiveness, denigrating the pleasures and joys of life, and lionizing sacrifice and the death instinct.

There is no doubt that the repression of the body and the elaboration of sophisticated mechanisms of criminalising it, its actions and desires by means of fatwas that reject art, music, cinema, social intercourse between the sexes, female display and the use of perfumes and so on, generate deviance and imbalance. The conflation of desire with sexual suppression, conjoined with intellectual repression and the dissipation of energy, provides the foundation for authoritarianism and its hegemony and surveillance over the spirit, the body and the mind.

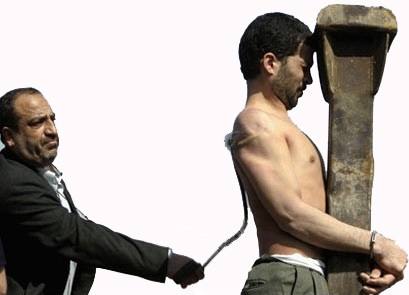

The blocking of natural tendencies and drivers does not diminish but rather remains active in the unconscious and continually grows, albeit in an unbalanced way. The victim of emotional deprivation is turned into a volcano afflicted by what the German psychologist Wilhelm Reich termed ‘emotional plague’. He develops a hostility to anyone who opposes his strict ethical system and declares anyone who fulfils his own self and defends it from confiscation by others to be an infidel. As the German psychologist states, you may observe such a man obsessed with the flogging, stoning, suppression and imprisonment of men and women whose instincts for life have not been killed off and who are not mortally struck down by the death instinct. Even if he manages to obtain some of what has been sexually suppressed and denied him, he obtains these only through a delusion of rebellion and under the weight of crushing feelings of guilt and shame (consider the cases of ‘urfī marriage[8] in Arab universities). For this reason we see him resorting to a desperate attempt to unconsciously atone for his sins by demanding that miscreants be flogged and adulterers stoned. Even if the latter have not infringed any taboo he will nevertheless exhibit violence and paroxysms against the Other who differs from him, not out of any zeal for praiseworthy morals but rather out of jealousy for anyone who has found the very courage – which has failed and betrayed him – to practise what are also his own hidden desires and infringe the code of what is enjoined and what is forbidden.

Feelings of inferiority

Since the 1980s crises in the global economic system have embedded themselves and widened the gap between the social classes. In this context global capital and its new financial astrologer experts have shown up the illusion of state financial resources and public services. To exploit these, cuts have been made at the heart of the health and social security sectors and compensation funds, and a number of public services have been abandoned to the private sector, services such as the post, transportation and education.

The result of this has been a marginalisation of the middle classes whose standard of living has visibly declined over the recent years, and who are now suffering from a decline in social status and a reduction in symbolic capital. They suffer from a mismatch between their scientific and professional qualifications which they strive for, and their social status and inherent prestige, and also from a broadening disdain for thought and knowledge, as opposed to an exaltation of the logic of profit and material benefit.

Suggested Reading

In this case, when an individual’s expectations associated with his social and conventional role, and others’ view of him, become ambiguous and unclear, he repudiates the prevailing values and seeks refuge in religious and mystical fantasy. This is what Max Weber observed when studying religious groups made up of the petty bourgeoisie, groups who joined the proletariat and to which he gave the term ‘proletaroid’. By means of a well-known but unconscious trick – reflex defence mechanisms – their deep sense of inferiority is overturned into a feeling of superiority and religious and ethical arrogance. This is usually accompanied by a stigmatisation of the Other who differs from him, and a general lamentation over moral disintegration.

Grass-roots groups that hitherto suffered isolation from the circle of development, knowledge and citizenship have transformed into missionary militias and achieved their cherished aim with the joys of authoritarianism and domination over others, guiding them to the True Path at times in an easy, simplistic populist style and at other times by means of crude violence. And since the joys afforded by violence can foster feelings of power, authority and superiority, it is in the nature of violence to act as a substitute for humiliation and a generalised complex of feeling disdained, and to express the ethics of envy and hatred that Nietzsche describes.

To conclude, in a time of tensions and anxieties (as Freud indicated) a collective neurosis is capable of sparing the individual the costs and pains of an intolerable personal and individual neurosis.

Reference sources

Theodor W. Adorno, Études sur la personnalité autoritaire (traduit de l’anglais par Hélène Frappat), Allia, Paris, 2007.

Sigmund Freud, Psychologie des masses et analyse du moi ,Broché, Paris 1982.

Erich Fromm, La Peur de la liberté; (traduit de l’anglais par C. Janssens), Buchet-Chastel, Paris, 1963.

Max Horkheimer, Théorie critique, Payot, Paris 1999.

Gérard Mendel, La Révolte contre le père: Une introduction à la sociopsychanalyse, Payot, Paris, 1968.

Jean-Louis Maisonneuve, L’extrême droite sur le divan, Psychanalyse d’une famille politique, Etude (broché), Paris ,1992.

Wilhelm Reich, La Psychologie de masse du fascisme, Payot, 1999.

[1] See Glossary under Tābiʽī .

[2] Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002), a French sociologist, anthropologist and philosopher who saw symbolic violence as a tool wielded by those who possessed symbolic capital (e.g., prestige, honour, attention). This symbolic capital is amassed through social and cultural inculcation and is therefore viewed by the victim as legitimate and justified. (Ed.)

[3] Erich Seligmann Fromm (1900 – 1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist, who fled Nazi Germany and established himself in the United States. Fromm held that freedom was a feature of human nature that we either embrace or escape. Embracing our freedom of will was healthy, whereas escaping freedom through the use of escape mechanisms was the root of psychological conflicts. He outlined three of the most common mechanisms of this escape: Automaton conformity, Authoritarianism, and Destructiveness. The first of these, Automaton conformity, is changing one’s ideal self to conform to a perception of society’s preferred type of personality, losing one’s true self in the process. It displaces the burden of choice from self to society. Authoritarianism is giving effective control of oneself to another, almost entirely removing one’s freedom of choice. Destructiveness refers to any process which seeks to eliminate others or the world as a whole, as a means to escape freedom – the destruction of the world being “the last, almost desperate attempt to save oneself from being crushed by it”. (Ed.)

[4] Herbert Marcuse (1898 – 1979) was a German American philosopher, sociologist, and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. During the Second World War he worked for the U.S. Office of War Information on anti-Nazi propaganda projects. (Ed.)

[5] Max Horkheimer (1895 – 1973) was a German philosopher and sociologist famous for his work in critical theory. In 1931 he took over the chair of social philosophy at Frankfurt University and subsequently intellectually reoriented the Institute of Social Research, integrating the views of Marx and Freud and their different conceptual structures of historical materialism and psychoanalysis. When Hitler was named Chancellor in 1933 the Institute was forced to close its location in Germany and Horkheimer emigrated to Geneva and then to the United States, where he continued his work at Columbia University. Through his critical theory Horkheimer sought to construct a total understanding of history and knowledge and revitalize social and cultural criticism. His work discussed authoritarianism, militarism and economic disruption, and he believed that the illnesses of modern society were caused by a misunderstanding of reason: if people used true reason to critique their societies, they would be able to solve any problems they might have. (Ed.)

[6] Theodor W. Adorno (1903 – 1969) was a German sociologist, philosopher and musicologist known for his critical theory of society, and was a leading member of the Frankfurt School. He is widely regarded as one of the 20th century’s foremost thinkers on aesthetics and philosophy and was a critic of fascism (Ed.)

[7] From Qur’ān III,110: Ye are the best community that hath been raised up for mankind. Ye enjoin right conduct and forbid indecency; and ye believe in Allah. And if the People of the Scripture had believed it had been better for them. Some of them are believers; but most of them are evil-livers.

[8] ‘Urfī marriage denotes a temporary ‘common law’ marriage which is officially unrecognised and unregistered, which takes place without the public approval of the bride’s guardian and which does not grant legal rights to the woman, including that of parentage to any children born of the union. (Ed.)