The predominant Islamic discourse is not suitable to the nature of knowledge and the challenges of contemporary life. It is, instead, a discourse that lies outside history, one which looks to the past for solutions to the problems of the present and the future.

IN THE NEWSPAPERS IN SUDAN not long ago it was reported that the imam and preacher of the Al-Nur mosque in Khartoum, Dr ‘Isām Ahmad al-Bashīr, issued a warning in his Friday sermon concerning the peril of the appearance of a group of ‘Sudanese agnostics’ and considered their emergence to constitute a danger threatening the faith of Sudanese society. The press that week also reported other news on the ‘apostasy’ of a young girl in the Al-Hāj Yūsuf district who had embraced Christianity.

In his sermon Dr. ‘Isām demanded that a discussion initiative be launched with the youth, who he described as “living in a cocoon on social networking sites” and called for the need to construct a discourse appropriate to their level of knowledge, to the age they are living in and to the challenges of their time. He added that “the discourse must be something they can closely identify with so that we do not miss the bus and find them fallen victim.”

What strikes one from the above expressions of the doctor is his propensity to give priority to the discourse of conversation and discussion over and against the language of punishment and repression that is prevalent among political Islamists. Such a discussion is to be commended and supported since it is in step with the spirit of the faith and the purposes of the law. In compliance with the divine directive, it does not confiscate the rights of men as to their freedom of opinion and choice:

There is no compulsion in religion. The right direction is henceforth distinct from error [Qur’ān II, 256].

The phenomenon of atheism is nothing new to Islamic culture since it was in evidence in its period of efflorescence, as well as in periods of decline. It did not come into conflict with society or with authority whenever there was a prevailing climate of intellectual freedom, openness and pluralism.

The phenomenon of atheism is nothing new to Islamic culture

When this culture was at its apogee, its intellectual, scientific and literary scene was dominated by prominent figures of the likes of the distinguished medic Abū Bakr al-Rāzī who, openly and without equivocation, declared his atheism. The same goes for the great ‘sly fox’ al-Rāwandī[1] who devoted his life to refuting what he called the ‘hocus-pocus of the Prophets’, writing more than 90 works which he named after precious stones such as ‘The Pearl’, ‘The Coral’ and ‘The Emerald’. Even so, he was not prosecuted and his books were not confiscated. There are many other scholars and poets and literary figures like him.

In our present age there are many thinkers and writers who have openly declared their atheism, such as the Iraqi poet Jamīl Sidqī al-Zahāwī, while during the 1940s in Egypt Dr. Ismā’īl Adham published his book Why am I an atheist? Despite this, he was not subjected to assassination, physical abuse or the confiscation of his works, while another thinker, ‘Abd al-Rahmān al-‘Īsawī simply wrote a riposte to him in the form of a book entitled Why am I a Muslim?

These examples clearly go to show that there is no danger to Islam from those who embrace atheistic thought, whereas the true danger stems from those who don the garb of religion and exploit it as a means for securing their corrupt, this-worldly aims. Anyone who looks into the causes that lie behind the growth of the phenomenon of atheism in the recent period will find that most often it is not purely the result of intellectual motives but a reaction to a type of prevailing Islamist discourse and practice.

The predominant Islamist discourse is not suitable to the challenges of contemporary life

The predominant Islamist discourse is not suitable to the nature of knowledge and the challenges of contemporary life – as Dr ‘Isām explained. It is, instead, a discourse that lies outside history, one which looks to the past for solutions to the problems of the present and the future. It is a categorically frenetic discourse which cannot accept any ‘other’ that differs from them, and which stands foursquare against the issues of the faith and its major objectives – chief among which is the question of ‘freedom.’ It contents itself with matters of surface form in the matter of speech and dress and the performance of ritual.

And not only that. Those imams, sermonisers and preachers who engage in religious discourse represent the greatest catastrophe to have befallen Islam, since they say what they do not do, they lend support to the rule of oppressors, and excel in the promulgation of fatwas of prohibition, while themselves remaining isolated from the conditions of the age we are living in. You will rarely find any of them able to speak a foreign language that might enable them to keep up with accelerating developments in science, technology and communications.

During a discussion hosted by the Al-Wafd newspaper in Egypt with the director of the website Atheist and Proud, Adil al-Masri (who had once been a member of the Islamic proselytising group Tablīgh wal-Daʽwa before becoming an atheist), the following question was posed – “As an atheist, do you see that religious clerics are aiding the spread of atheism?” To which he replied:

Absolutely. For instance, Abū Islām[2] was one of the greatest assets to atheists, and for me personally, for instance, the Shaykh Abū Ishāq al-Huwaynī was the first one to light the spark of atheism in my mind, particularly when he spoke of the ‘adulterous ape’, or ‘the breastfeeding of an adult’ or ‘the camel’s urine’. I think that the same effect happens when priests of the Salafist trend speak, such as Muhammad Hasān and Husayn Yaʽqūb and ‘Abd Allā Badr and others – the list is long.

“Even Shaykh Muhammad Hasān?”, he was asked, to which he replied: “I saw a picture of Muhammad Hasān riding in a Hummer SUV; yet he demands that others adopt austerity, avoid extravagance, and give alms while people like him live in palaces and drive the fanciest cars as they weep for the poor.”

What is odd about the prosecution of the young girl in Al-Hāj Yūsuf for apostasy was the opinion of the ruling party, in that in the body of the news item it was reported that the National Congress Party “downplayed the incident of the girls apostasy from Islam in Al-Hāj Yūsuf and described it as not a matter of great concern on the grounds that it was not a widespread phenomenon.”

The principal oddity is that the ruling party should choose to downplay the importance of prosecuting the girl on the grounds that it has not become a ‘phenomenon’, in the sense that it is a matter which does not at present stir up controversy and should therefore be overlooked – as if it were saying that there is a specific level that the number of apostates would have to reach before it became a ‘phenomenon’ that had to be dealt with. On what grounds, then, should one ever apply Article 126 of the Penal Code[3] if this were the opinion of the party?

Authoritarianism and religious oppression can only ever act to damage religion

This statement clearly indicates how religion can be employed for political ends. Were the ruling National Congress Party, to be sure, not at present clinging desperately to the reins of power it would have happily stirred everyone up rather than calmed them down, and we would have heard many diatribes from its leadership on the danger that Muslims were being exposed to in Sudan, and the ‘organised Crusader campaigns’ that were targeting Islam!

Central to the question of apostasy is the fact that Islam is a religion of freedom and justice, and does not punish anyone who abandons it in this world, but rather leaves the reckoning to the Lord of the Worlds at the Day of Resurrection where the perpetrator will be replaced with someone better:

O ye who believe! Whoso of you becometh a renegade from his religion, (know that in his stead) Allah will bring a people whom He loveth and who love Him, humble toward believers, stern toward disbelievers, striving in the way of Allah, and fearing not the blame of any blamer. Such is the grace of Allah which He giveth unto whom He will. Allah is All-Embracing, All-Knowing [Qur’ān V,54]

The government would therefore be better advised – before it embarks on prosecuting apostates – to ask itself what the hidden causes are behind the increase in the phenomenon of apostasy from Islam a full quarter of a century into a rule which they fanfared with religious slogans and the promise of applying the Sharīʻa. How did all these restrictions, all this injustice, nepotism and repression lead to people turning away from religion? Why is that in Sudan the condition of Islam and of the Muslims was superior before the arrival of the National Salvation Government?

No doubt the answer to these questions will lead us to a more progressive view – that authoritarianism and religious oppression can only ever act to damage religion, and that the condition of the faith can only flourish in an atmosphere of freedom, tolerance and openness. Perhaps this goes to explain why Islam is the fastest-growing religion in western countries.

Results published by a two-year survey undertaken by the American Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, covering 230 states and geographical regions across the globe, demonstrate that the number of atheists in the world now stands at 1 billion, while Christians number 2.2 billion and Muslims 1.6 billion.

Suggested Reading

The findings of this survey indicate the impossibility of putting an end to atheism in the world, and that one must simply accept this fact as an unavoidable reality. Yet on and beyond all of this, it illustrates the Divine Will concerning creation, as demonstrated in the Qur’ān where the Prophet is addressed thus:

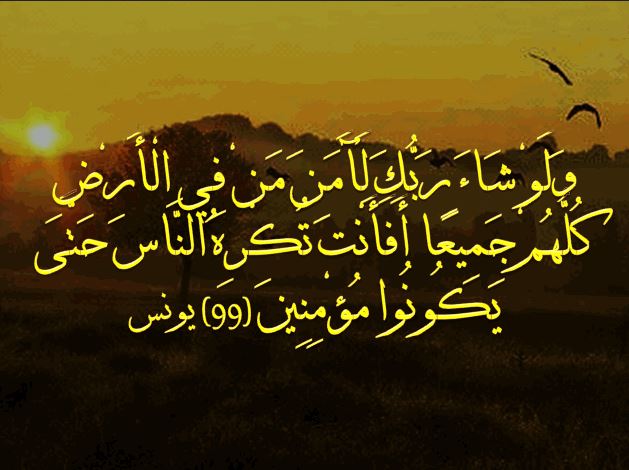

And if thy Lord willed, all who are in the earth would have believed together. Wouldst thou (Muhammad) compel men until they are believers? [Qur’ān X,99]

The results of the survey also indicated that the tally of Muslims increases by 2.9% per annum, a figure that exceeds the annual population growth in the world, which stands at 2.3% – indicating that Islam is not in danger and that the number of Muslims is continually on the rise. So what, therefore, is the purpose of prosecuting a girl in Al-Hāj Yūsuf for declaring that she had forsaken Islam and embraced Christianity?

In conclusion we may say that Islam granted humanity the freedom to believe or to disbelieve, but that they will bear the results of their choice in the Hereafter and not in this world:

Say: (It is) the truth from the Lord of you (all). Then whosoever will, let him believe, and whosoever will, let him disbelieve. Lo! We have prepared for disbelievers Fire. Its tent encloseth them. If they ask for showers, they will be showered with water like to molten lead which burneth the faces. Calamitous the drink and ill the resting-place! [Qur’ān XVIII,29]

[1] Abū al-Hasan Ahmad ibn Yahyā ibn Ishāq al-Rāwandī (827-911 AD) a one-time Muʽtazilite scholar, who subsequently embraced Shīʽa Islam before becoming a freethinker who repudiated Islam and denounced religion.

[2] Shaykh Abū Islām has become infamous recently for his aggressive antics such as burning copies of the Bible, threatening Christians, and declaring it permissible to ‘rape’ female protesters – on the grounds that they wanted to be raped or are probably Crusaders.

[3] Article 126 of the 1991 Sudanese Penal Code stipulates that: 1) Any Muslim who promotes the forsaking of the creed of Islam or who declares openly having forsaken it by a clear statement or an unequivocal act shall be deemed a perpetrator of the offence of apostasy; 2) He who commits the offence of apostasy shall be called upon to repent and shall be given a grace period that shall be fixed by the court. If he insists on his apostasy and in case that he is not a recent convert to Islam he shall be executed; 3) The punishment for apostasy shall be rescinded as soon as the apostate turns away from his apostasy before the implementation of the punishment.