One ought to acknowledge at the outset that no consensus exists on any interpretation or clearly specific reason for any elucidation of a Qur’ānic verse. Everyone gives his opinion according to his doctrine, his sect or authority figure.

BY YUSUF YUSUF

THIS IS BECAUSE the Prophet himself did not interpret the Qur’ānic sūras and verses, with the exception of a few. ‘Alī Gomaa the former Muftī of the Republic of Egypt, had this to say on this point:

The Holy Qur’ān was not interpreted in its entirety during the era of the Messenger of God, but the Prophet gave an interpretation to some of the verses that proved difficult for the believers, and these amount to no more than about 200 verses.

At a meeting with the programme And God Knows Best, Dr. Gomaa added that

Whatever the Prophet did interpret from the Qur’ān we shall not deviate from that, and it will be considered the final word that admits of no new interpretative ijtihād[1].

On this we should highlight the following point: Is there any document in existence that confirms that the Prophet interpreted only 200 verses, given that the number of verses of the Qur’ān is much more than this number and that the number of verses in any case is not agreed upon? On the number of verses of the Qur’ān, the website Mawḍū‘ states:

Scholars agreed that the number of verses of the Qur’ān amounts to 6200 verses, but their opinions varied: some said: 6204 verses, others 6214 verses, others said 6225 verses, and still others said 6236 verses.

Even the Companions of the Prophet did not have the faculty of jurisprudence required to interpret some Qur’ānic verses. An example of this is the Qur’ānic verse 31 of sūrat ‘Abasa which has the phrase wa-fākiha wa-abba – ‘And fruits and grasses’. The website Al-Qur’ān has:

By fākiha (‘fruits’) is meant the colours of the fruits, and by grasses abba (‘grasses’) is meant pastures unsown by men but what cattle and horses feed upon … Qatāda speaks on these as: ‘fruits are for you and grasses are for your cattle’. But the Companions were unable to give an interpretation for it, while others noted that: ‘It was narrated from Ibrāhīm al-Taymī that Abū Bakr was asked about this phrase wa-fākiha wa-abba. He replied: “What sky will shade me and what land will support me if I say what I do not know about the Book of Allah ?” Ibn Shihāb narrated from Anas that he heard ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb recite this verse and then say: “All these things we know, but what is abb?” Then he raised a stick that was in his hand and said: “By Allah, this is mere dissimulation! What is the matter with you that you do not know what abb is? He then replied: “Just follow what is clear to you in this Book, and what is not clear, leave aside”.

Now if the Companions, who accompanied the Prophet, are ignorant of the meaning and interpretation of the verses how are the general public to interpret them?

By the way, the word abb is the Syriac ܐܒܒܐ ebba meaning ‘ripe fruit’ or ‘the produce of the earth’ and the verb abābā in ancient Chaldean denotes the earth ‘bearing fruit’. The Companions, the Tābi’ūn[2] and the people of Muḥammad were unable to interpret this word because it was Syriac.

If the Companions of the meaning of the verses, how are the general public to interpret them?

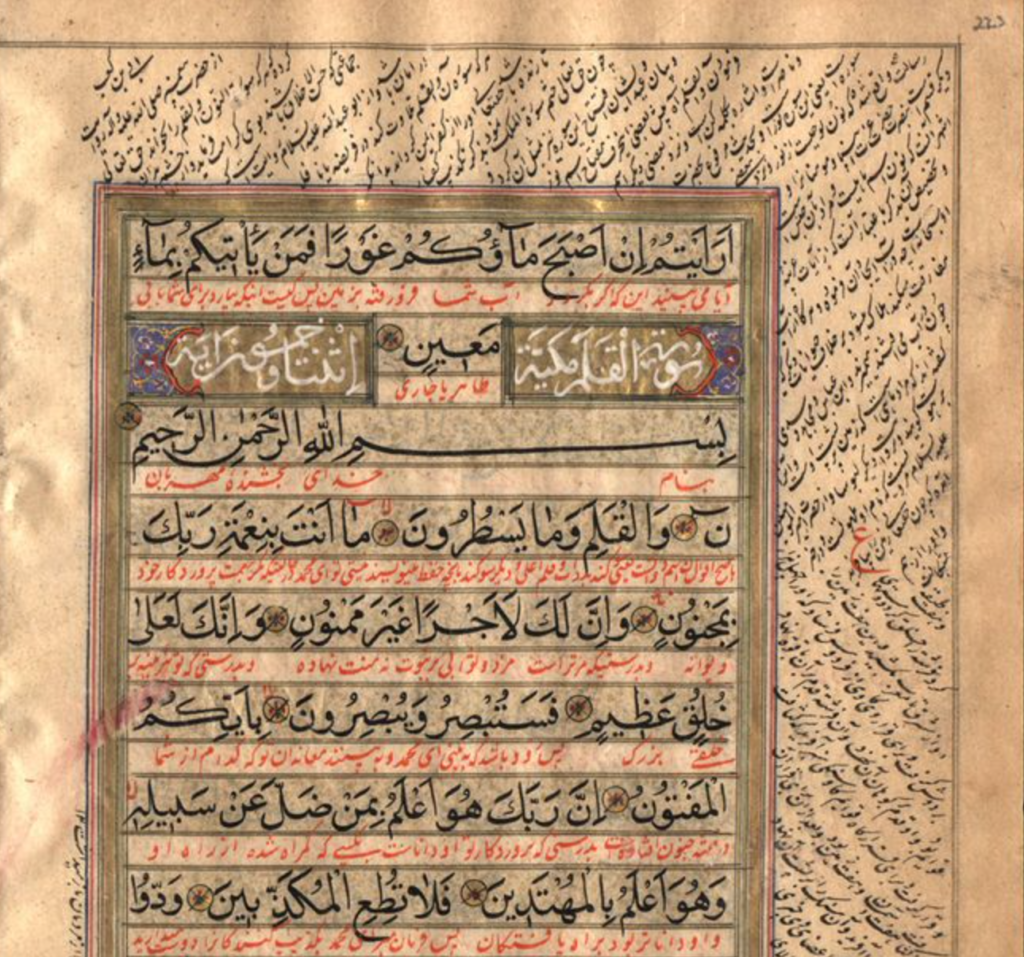

Because of the different interpretations of the Qur’ānic verses, and the large number of these interpretations, dozens of books of tafsīr have emerged, the most famous of which according to the website al-Mirsāl is the Jāmi‘ al-Bayān fī Tafsīr al-Qur’ān known as Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī; the – Tafsīr al-Kashshāf; the Tafsīr al-Zamakhsharī; the Tafsīr al-Qur’ān by Ibn Kathīr and the al-Jāmi‘ li-Aḥkām al-Qur’ān by al-Qurṭubī. The problem is that the number of books of tafsīr has exceeded all expectations. The website Multaqā Ahl al-Tafsīr notes that

It is said that there are 5,000 interpretations for sections of God’s Book, and that the number of tafsīrs totalled 500. This large number is indication of the care our scholars took regarding our Lord’s Book. The left no section or question without authoring a work on it. The number of extant tafsīrs, including printed explanatory sections numbers 200.

Referring to the problematic issues in the tafsīrs, in addition to the ideological, jurisprudential and intellectual points of difference, the political and governmental conditions and the changes of society in space and time, Islamic schools of thought emerged. Of the many schools of jurisprudence that there are, the four Sunnī schools of jurisprudence are the most widespread and have the greatest presence in the Islamic world. These are the Ḥanafī school of Imām Abū Ḥanīfa al-Nu‘mān ibn Thābit (80-150 AH), the Mālikī school of Imām Malik ibn Anas (93-179 AH), the Shāfi‘ī school of Imām Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfi‘ī (150-204 AH) and the Ḥanbalī school of Imām Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal (164-241 AH). There are dozens of other schools of thought, including the doctrine of Shaykh Al-Islām Ibn Taymiyya, Ibn Ḥazm, Imām Zayd, the Jarīrī, al-Awzā‘ī, Ẓāhirī and al-Thawrī schools, and we may add to these the Ibāḍī doctrine.

The Quranists thus kill off the hadith and the Sunna altogether, and the whole enterprise of tafsīr is curtailed

The view of the Ahl al-Sunna wal-Jamā‘a[3] is that Shi‘sm in general (doctrinally as well as jurisprudentially) is a heresy alien to Islam, and according to the article of Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Raḥmān – on the website Al-Yawm al-Sābi‘:

The scholars of the Ahl al-Sunna wal-Jamā‘a have agreed, both anciently and today, that Shi‘sm is an extraneous oddity in Islam, a heresy to the Islamic faith, and it did not exist in the era of the Prophet or that of his successors Abū Bakr al-Siddīq and ‘Umar Ibn al-Khaṭṭāb.

Nevertheless the Shi‘a shaykhs take a different view, and the website of Shaykh Muḥammad al-Quṭayfī states the following:

The Imāmī Shī‘a believe that the doctrine of Ahl al-Bayt[4] originated during the era of the Holy Prophet Muḥammad, and that the first person who planted the seed for this, nurtured it and preserved it was the Prophet himself. We know this from the texts issued about him which indicate the necessity for following Alī the Commander of the Faithful, that his adherents are the ones who will be the victors on the Day of Resurrection, and that he and his companions are the finest of Mankind.

In recent decades a new interpretation of the Qur’ānic text has emerged, one based on the Qur’ān itself. This group is called Ahl al-Qur’ān, the People of the Qur’ān, and its leading pioneer is the Egyptian Islamic thinker Dr. Ahmed Sobhi Mansour (born March 1, 1949). He was a one time teacher at Al-Azhar University but was dismissed in the 1980s due to his denial of the Prophet’s verbal Sunna (the Hadith), and his founding of the ‘Qur’ānic method’, which confines itself to the Qur’ān as the sole source for Islamic legislation. The ‘Quranists’ explain that

the hadiths, no matter how authenticated they may be, are ẓaniyya al-thubūt (of hypothetical authenticity) as the jurists confirm, and the Quranists refuse to understand their faith or construct religious legislation based on hypothetical sources.

The Quranists thus kill off the hadith and the Sunna altogether, and the whole enterprise of tafsīr is curtailed, in that the Qur’ān interprets itself.

Referring to all of the above, it is clear that there are hundreds of books of Qur’ānic tafsīr because the Prophet gave interpretations for but a little of the Qur’ān. On the website of Bin Bāz the following explanation for this is given:

The Prophet used to give many explanations, reading the Qur’ān to them to show them its meaning, sometimes in councils, sometimes in sermons, and sometimes by reciting the Qur’ān to them to meet their needs.

The question here is this: How did the Prophet read the Qur’ān to them if he was the ‘illiterate prophet’? Moreover, the various initiatives of ijtihād and the multiplicity of tafsīrs served todivide Muslims up into dozens of denominations, sects and groups, which moved the Prophet to say:

“The Jews split into seventy-one sects, and the Christians into seventy-two sects, while this [Muslim] nation will be split into seventy-three sects, all of them except one destined for Hell.” He was asked: “Which is that one, O Messenger of Allah?” To which he replied: “The one that follows me and my Companions.” In some accounts, he is to have said: “It is the jamā‘a (‘the community’)”.[5]

And every sect or group says: “We are the Victorious Sect”!

From the above, it is clear that the faith of Islam and the Muslims remain in the shell of a tribal past, and despite the centuries is yet to emerge. The Islamists, parties, groups, shaykhs and preachers hold that Islam is valid for all times and places, that it exited the scope of time and space, of history and civilization, and alone remains to struggle with one problem after another.

Suggested Reading

Jurists – “We must perfect religion – Qur’an – “We have done that”

The shaykhs, the public, the thinkers and advocates of Islamic belief, are continually attempting to create and to evoke an Islam of the past, oblivious that Islam needs to modernize the features of its belief – the texts, the traditional practices, the hadiths – regardless of the various interpretations (literal or allegorical) or the asbāb al-nuzūl (reasons for the revelation), in order to keep pace with people’s beliefs, with the modern age and social civilisation. The faith does not need to refine or reform the religious discourse to be acceptable, as is often rumoured. For a faith that has languished in its cocoon for eons, will be suffocated by that cocoon.

[1] The implication of the Muftī’s statement is that most of the other verses are indeed subject to ijtihād (On the meaning of Ijtihād see Glossary).

[2] ‘Followers’, that is, the generation of Muslims who were born after the death of the Prophet Muḥammad but who were nevertheless contemporaries of the Sahāba (‘Companions’) (Ed.)

[3] ‘The People of the Sunna and the Consensus’. See Glossary: Ahl al-Sunna wal-Jamā‘a.

[4] The Ahl al-Bayt – ‘People of the House’, are the family of the Prophet Muḥammad. Among the Shī‘a the term is limited to Muḥammad, his daughter Fāiṭma, ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib and Ḥasan and Ḥusayn. Sunnīs extend the term to cover all descendants of Muḥammad’s clan the Banū Hāshim. The Shī‘a particularly hold the Ahl al-Bayt in the highest esteem as the rightful leaders of the Muslims following the death of the Prophet. (Ed.)

[5] For these hadiths, see: https://sunnah.com/ibnmajah:3992 and https://sunnah.com/tirmidhi:2641